On Aug. 25, at 11:50 a.m., the Campus Police Department (CPD) circulated a chilling email to students and faculty—in the middle of the night, a student reported that an unknown subject entered their dorm room. Administration was quick to respond, attempting to bolster campus security by increasing police presence on the residential side of campus. As part of this rollout, officers of the Sarasota Police Department (SPD), the Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office and members of Sarasota Bradenton International Airport Security were brought on to campus to help. However, many students expressed great reluctance or apprehension towards the police presence, citing discomfort around increased surveillance, skepticism over their usefulness and concern over the SPD’s controversial history around police brutality and racist policing. This reignited conversations on how community safety should be approached at New College, the ideal relationship between police and students and what measures administration should take in the meantime.

“I think students feel more comfortable dealing with us, and we feel more comfortable that campus police officers show up at your place rather than another jurisdiction,” CPD Chief Michael Kessie said.” Although they [police from other departments] can show up, it’s certainly within their right to do that. But we prefer to handle our campus. We just don’t have enough people to do what we need to do.”

Kessie referenced the staff shortages the CPD was currently experiencing due to members contracting COVID-19, being injured or taking time off.

“Usually, we can handle it,” Kessie continued. “But you start losing four or five people, and you’re losing a third of your department.”

The CPD has increased the frequency of its patrols at night, moving shifts around and offering overtime opportunities to officers on vacation. Even so, they brought in other local departments to fill the needs caused by the latest intrusion.

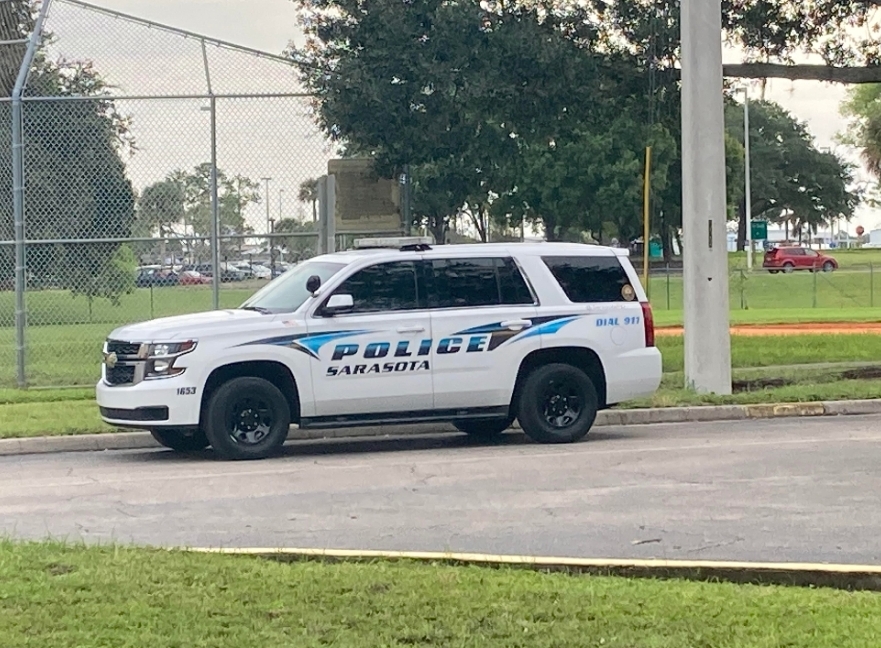

Among these forces, the involvement of SPD has received the most attention. Over the years, several protests in Sarasota have received attention nationwide, accusing the SPD of systemic discrimination against people of color, excessive brutality and non-accountability.

“Sarasota has a long corrupt history of cover-ups, settled lawsuits [and] rehiring officers fired for excessive force,” Greg Cruz, an organizer and photographer from Answer said in a written statement to the Catalyst in 2018.

The police culture Cruz spoke of may still haunt Sarasota today. On June 4, 2020, a video surfaced online of an SPD officer kneeling on a black man’s neck during an arrest.

Consequently, the idea of placing SPD on campus gave some students pause, despite a unanimous agreement on the need for greater security.

“I have mixed feelings about it,” first-year Ellie Elliott confessed. “There is a history with SPD, a pretty racist history, and since we are a relatively white campus, I feel like people of color on campus might be targeted. So I’m a little concerned about that.”

Others felt similarly, citing the SPD’s lack of a structural relation to New College.

“They don’t have the same priorities on the administrative level,” first-year Ben Hughes noted, “The CPD would typically be more concerned with keeping the students safe.”

“We’re not putting them on routine calls,” CPD Captain Kathleen Vacca reassured. “They’re not coming into the station to handle things and being dispatched. They’re just simply supplementing as time allows by coming into our area and doing what we would call high profile, meaning very visible. Going down the streets looking for anything that seems suspicious. We’ve shared some intelligence and asked them to be on the lookout for that.”

While some found the extra surveillance disconcerting but ultimately necessary, others asserted that community-based security measures would have been a better route.

“I do think [the increased police presence] is appropriate,” president of the Black Student Union and thesis student Ginelle Swan said. “I do also have to consider the increased presence in relation to the black students that I represent. I hope that eventually, they won’t always have to be patrolling and be guarding because it is a little bit unsettling, but for now I think it’s appropriate. As much as my mentality is more towards redoing police forces from the ground up, I think there’s also no one else who’s hired to handle a specifically dangerous or physical situation like that.”

“There are a lot of better ways of increasing campus security than by having police officers come onto campus,” Hughes countered. “You’re not going to catch someone on the middle of the sidewalk. It’s going to be something that’s reported.”

Some of the measures mentioned as alternatives included installing more sophisticated locks, greater access to door alarms and safety bars for rooms with balconies, creating a community watch and building a fence around the residential side of campus. The construction of a fence would be a significant change for New College, which has traditionally been an open campus. Still, most students seemed in ardent support.

“I definitely think [there should be fences].” Swan added, “During Walls my first and second year, I’ve had people from off the street just walk over the little hill and talk to me. People see flashing lights and a stage and they’re like, ‘Let me go!’ Even though they’re not a student. People get their bikes stolen, their boards stolen—I think New College should definitely close off at least the residential side of campus.”

Another proposed measure was adding more surveillance cameras to New College, to which Vacca extolled their benefits.

“When cameras are on campus like they are at the University of Florida, then police can have a lower actual presence,” Vacca explained. “And they and their vehicles are not out necessarily quite as much, because then the officers can rely on video to tell them if there seems to be a problem. When you have a camera, you have a great tool or friend to help you proactively monitor an area and go back and view recorded tapes for evidentiary purposes. They’re not meant as an invasion of privacy.”

Students were hesitant to accept the cameras, fearing that they would be used to monitor for micro-crimes or be overly invasive, but many implied reluctant acceptance if it truly meant that police presence would lessen.

“I feel like I would rather have increased camera presence over increased police presence, assuming that the cameras are only being used, that there’s not gonna be a surveillance thing,” first-year Alaska Miller said.

While few deny that these alternatives would be helpful, some insisted that the police presence was necessary for the time being.

“I ran on a platform of decreased police presence on campus,” New College Student Alliance (NCSA) President Sofia Lombardi said. “Ideally, we would be able to live on a campus where police presence is extremely minimal, especially on our residential side. Right now, I feel like increased police presence is the only way to respond to this crisis because we don’t have alternative resources in place.”

Yet, all of this begs the question—why are students so wary of CPD presence on campus? Unlike most police forces, minor crimes involving students are deferred to Student Affairs, their records are completely transparent and they have rigorous and stringent hiring practices, as Kessie was quick to point out.

“We tell them when they come in the door,” Kessie said. “If you don’t like a diverse community, if you’re not accepting of people of different ideas, race, sexuality, then you’re in the wrong place. Some people say, ‘We’re scaring them away!’ But we’re telling them the truth—because we don’t want that kind of person. You have to be able to be accepting and understanding and still be able to do the job. It’s not easy to find people who will step in and do that. We are [doing high level screening] and we’ve been doing that for years. I mean polygraph tests, psychological tests and thorough background tests.”

Students who have been attending New College for a longer amount of time often admitted that their interactions with CPD were more positive and professional than with other police forces.

“Back home, anywhere outside of New College, my interactions with police haven’t been the greatest,” Swan said. “Whether it’s me directly, my loved ones, someone I care about, or someone I’m protesting for, they haven’t been great experiences.”

If the CPD is different from most police forces, why do students still feel uncomfortable with their presence on campus and at student events? Some students said that while the CPD may have a different record, they look the same as any other department. Their appearance has a symbolic meaning; students can’t help but associate that appearance with the mistreatment received elsewhere.

“Their uniform definitely means something,” Swan emphasized. “Seeing it, their weapons and their badge and all of that. Their uniform has a meaning in people of color’s eyes. So that immediately is like a tense situation. Things get awkward, like unfriendly, quickly. A big thing for me is that [police] can have their weapons on them but have it more concealed. Less obvious. Because at that point you don’t feel like they’re patrolling for you. It feels like they’re coming there to make sure you’re not ‘messing up’.”

Swans’ statement illuminates an aspect of why some consider the increase of police presence problematic—people of vulnerable demographics or those who fear the police are having their access to public spaces restricted.

“I think it’s a natural reaction for students of color on campus to minimize their interactions with the police force,” Swan continued. “So if a police officer is coming to an event, I’m going to leave the event, I’m going to go the other way. Not because I’m doing anything wrong, because that’s just the environment I grew up in.”

Furthermore, while the CPD has a cleaner record than most police departments, that does not mean there haven’t been issues. Six months ago, former President Donal O’Shea formed the Ad-Hoc Presidential Commission meant to address student grievances and create a more robust line of communication between students, administration and police.

In a presentation helmed by Lombardi over Zoom in the spring semester of 2021, the Ad-Hoc committee gathered dozens of student reports accusing officers of performing sexually inappropriate behavior, racial profiling and general misconduct.

When asked about the report, Kessie urged caution.

“I’ve had a conversation with President Okker, and I have talked to Sofia about it,” Kessie said. “I would just caution one thing, and that is when we look at the Ad-Hoc report and some of the accusations that are made, which are proven and which aren’t. It’s the same as if someone would make an accusation about you. We would prefer the same courtesy, that instead of people coming up and saying, ‘Here’s what you did’, them saying ‘Let’s find out.'”

Kessie then recounted the difficulties in investigating the claims. He claimed that many of the reports didn’t include first-person accounts, badge numbers, faces or names, making it challenging to take punitive action or initiate change. However, he made it clear that he has no problem with students filing complaints and wants everything about the CPD to be as transparent as possible.

“We are very open,” Kessie said. “You ask me for a report, we’re going to give it to you open, open, open. We just do not sweep things under the rug.”

When asked whether Kessie might support a database that allowed students to file, track, and substantiate complaints publicly, he said that he would not be opposed to it. As a caveat, he added that it would have to be within the boundaries of the law and their collective bargaining agreement with the police union.

The possibility of such a database is a positive sign for student-police relations, yet it may be one of many. The recommendations set forth by the Ad-Hoc presidential committee, which the administration temporarily put on ice during the transition between school presidents, have resurfaced.

“It is now time to return to that report and its list of recommendations to determine the appropriate actions for our campus,” Okker wrote in a recent email to students, faculty and staff. “We plan to have opportunities for the campus to respond to that report and to share with the campus community a timeline of actions taken and planned.”

Attached to that email was a copy of the Ad-Hoc Presidential Commissions report, which contained an extensive list of campus safety and policing recommendations. Some of these recommendations included renaming the CPD to the Office of Campus Safety and having officers attend campus events out of uniform, working more closely with the Counseling and Wellness Center (CWC), reporting to Student Affairs instead of administration, and utilizing non-sworn and student personnel. Furthermore, the report proposes both a complaint-filing process overseen by an independent authority, and a permanent advisory board composed of students, faculty, administration and local members of the community which would mediate dialogue.

If the Okker administration and the student body agree to implement these changes, it could signify a meaningful transformation for student-police relations. However, even though the Ad-Hoc Presidential Commission proposed these recommendations, it does not mean that administration will enact them, even after meeting with students. That decision ultimately rests with Okker and the Board of Trustees. While Kessie did refer to Okker as “a woman of decisiveness,” only time will tell if this will all bear fruit.