On Tuesday, Oct. 13, third-year Jessica Edmonds was in the middle of an online class at her parent’s home in Tallahassee when her roommate, thesis student Jacob Lough, called. Edmonds waited until class was finished to check her phone, only to find that Lough had texted her: “I’ve tested positive for COVID-19.”

She and two of her roommates were randomly selected for COVID-19 testing at the Counseling and Wellness Center (CWC). Edmonds, Lough and third-year Jude Zelznak each got tested on Oct. 12 and Edmonds drove home immediately afterwards.

“I was freaking out because no admin or Anne Fisher [or the] CWC [had] contacted me yet and I had already gone home,” Edmonds said. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve given COVID-19 to my parents.’”

Both Edmonds and Zelznak later learned that their results were negative. But after receiving texts from Lough, they both found themselves scrambling to learn their test results and secure a place to quarantine. Lough called and texted multiple students he had been in close contact with when he learned that he had tested positive, including third-year and Catalyst staff writer Willa Tinsley—Lough’s fourth roommate and the only one not called in for random testing on Oct. 12—first-years Benjamin Casey and Jack Nisa and thesis student Ella Rennekamp, living off campus.

All seven students entered quarantine on Oct. 13, with four staying on campus and three quarantining elsewhere. Each of them were faced with wildly different situations, from living conditions to balancing coursework and even to their release dates. But each of them also had something in common: complaints about communication from both New College administration and the University of South Florida (USF) and the lack of support and clarity offered to them.

Life in “The Box”

Whereas most students are alerted either by the CWC or a representative from housing when they need to go into quarantine, Lough contacted each of the aforementioned students as soon as he received his test results on Oct. 13. Lough’s test results appear to have been the only ones available at this time, and Senior Associate Dean for Student Affairs Mark Stier says that the time frame to receiving test results varies, but is generally within “48-72 hours [of being tested], sometimes less.”

“Once Resident Life is notified of a positive [test result], we contact the student and assist them [in] locating to quarantine immediately,” Stier said in an email interview, with additional contributions from Associate Director of Residential Education Nicole Gelfert, Interim Dean of Students Randy Harrell and Director of Counseling and Wellness Anne Fisher.

All students are provided with the option to quarantine either on or off campus. Students that stay off campus are responsible for their own arrangements and are not allowed back on campus until they are cleared by the CWC and USF’s Student Health Services (SHS).

Students that choose to stay on campus spend their quarantine in designated dorms in the Pei residence halls, where they remain in isolation.

“At the outset of [on campus] quarantine, the expectations for behavior are clearly communicated to students and they are asked to complete a form acknowledging that they understand and agree to what is outlined, including the limitation of remaining in their quarantine space,” Stier said. “If a student were to break quarantine, they may be asked to leave campus for the remainder [of their quarantine], as their actions could pose a risk to our community that we take very seriously.”

Zelznak was off campus—en route to visit family—when they had gotten the news from Lough, and received a call from Stier in order to establish where they would be quarantining. Zelznak was not able to receive test results at the time, so they returned to campus in order to avoid potentially infecting their parents. Other students, such as Tinsley, opted to quarantine off campus after learning that students quarantining in Pei are not allowed to leave their rooms for any reason, use their balcony or open any windows.

“Are there guards stationed outside the door? How do they stop people from going out for any reason?” Tinsley said she asked Stier when speaking with him. “He was like, ‘All the police and everyone on campus, they have your face, they have your name. Just recently a girl who was in quarantine went out for a smoke break and they caught her immediately and she was escorted off campus. You don’t want that to be you, do you?’ That’s crazy, right?”

Even for Zelznak, who opted to quarantine in Pei—in what they and their roommates would come to refer to as “the box”—not being allowed fresh air when there was the potential that they had COVID-19 was “counterintuitive.”

“The reason I wanted [to be in] Pei quarantine was because I did take this seriously,” Zelznak said. “It matters to me that I have the potential to be carrying the virus. [But] I think that that rule—especially when you’re locked in a box for two weeks straight and you’re technically not allowed fresh air unless you’re opening your door to get food or [to take] your trash out—it’s not healthy.”

Zelznak also complained that the floor of their room was visibly dirty when they arrived, but Stier says that facilities sanitize each room once the student is released. The Pei dorms are also known to have turbulent Wi-Fi and cell service, something that proved detrimental to quarantined students who needed to make calls, schedule appointments and attend online classes. Even students quarantining off campus had trouble balancing appointments with classes, as Tinsley claims that she needed to have telehealth appointments during her Zoom classes multiple times because there were no other time slots available.

“You’re still in there doing all your Zoom classes and trying to explain to your professors why you’re not showing up to Zoom calls because you have no Wi-Fi,” Zelznak said. “It’s kind of taxing.”

A Breakdown in Communication

For students in quarantine, communication between NCF administration and USF nurses and doctors is not only crucial for evaluating their health and determining a release date, but also might be the most consistent interaction they have while in isolation. Even so, students quarantining both on and off campus described attempts to communicate between NCF and USF as irregular and even occasionally misleading.

“From my understanding, everybody that was in the Pei quarantine was talking to various USF doctors and a lot of them were giving contradicting information,” Zelznak said, “As to days we could potentially be let out, what the necessary time after exposure is to be cleared from potentially being tested on the thirteenth day, stuff like that.”

Lough, who quarantined on campus, described receiving conflicting information when it came to the amount of time he would be isolated and scheduling the required appointments that would let him be released.

“It was so weird because the first couple of days, so many people were giving me mixed information,” Lough said. “I didn’t know what the rules were. The whole thing was a blur.”

Edmonds, who stayed in Tallahassee for her quarantine, said that she had called the CWC after she received the text from Lough in order to find out her test results. She was told that no results were in yet and was instructed to email Fisher, who later told her that she tested negative. Even so, Edmonds says that the following day Fisher, Stier and someone from USF Health all called her for details on her situation.

“They were like, ‘Jessica, we’ve been trying to get in contact with you,’” Edmonds said. “‘We want to know if you’re off campus [or] if you’re in isolation. Let us know.’ No one had tried to contact me. I had tried to contact everyone the previous day, so I just found that interesting.”

Even Rennekamp, who both lives and quarantined off-campus, describes receiving contradictory information from New College and USF. Rennekamp attributes some miscommunication to her inability to use the USF symptom tracker, something she and many other students have struggled with this semester. Rennekamp said that she initially called the CWC when Lough had texted her and was redirected to USF to schedule an appointment for testing. From there, she was told that her NCF email was not in the USF system and that she would need to use the symptom tracker before scheduling a test.

“I was directed to talk to an IT member at both NCF and USF to try to get the symptom tracker on my computer,” Rennekamp said. “NCF IT said USF handles symptom tracking, but USF IT said they couldn’t do anything for me because I’m a NCF student.”

Rennekamp was scheduled for a random testing during her quarantine without gaining access to the symptom tracker, but gaining the test results proved to be an additional challenge.

“By the first Friday of quarantine, I still hadn’t gotten my results back, so I called the CWC and they said they didn’t have them. The following Monday I called and Anne Fisher said she thought someone already called me last week to tell me they were negative.”

Rennekamp’s experiences with miscommunication between NCF and USF culminated when her boyfriend, who no longer attends New College, received an email at the end of her quarantine telling him that his test results came back negative, despite never testing with New College.

Tinsley had a similar experience when she got a call near the beginning of her off-campus quarantine from USF and spoke to a man who told her that she had tested positive. She had not been tested yet. Tinsley was eventually tested by the CWC, but was also initially told by USF that she would need to come to Tampa in order to be tested by them.

Testing aside, Tinsley said that she was especially annoyed by the telehealth appointments that students in quarantine are required to have, where the student is asked to list their symptoms.

“They only tested me one time late in the game [but] I had to do multiple telehealth appointments,” Tinsley said. “That was very important to them [but] it’s also a huge nuisance and very difficult to schedule. And your release is totally dependent on those.”

Perhaps most bafflingly, while attempting to schedule his final appointment with USF in order to be released, Casey’s phone calls were answered by a nurse who didn’t know what New College was.

“After talking about how I was supposed to get out [that day, and saying] ‘I’m in quarantine at New College,’ she was asking where New College is and what it was,” Casey said. “I mean, you should probably know.”

While Zelznak chalks up most of these incidents to disorganization, they also remarked on an instance of miscommunication that could have been dangerous. The doctors from USF that Zelznak had spoken to were very clear on the importance of a two-week long quarantine, and told them that there have been cases where someone had initially tested negative until the thirteenth day, when they tested positive. Zezlnak says that despite these warnings, they were only tested once in the first week of their quarantine.

“If we had tested positive on the thirteenth day, they had no way of knowing,” Zelznak said. “In my head, I’m like, ‘Well, why aren’t you testing me again?’ Nobody who was tested previously was tested the day or two before their release. That was really odd because that seemed like the most strict thing that they were following and yet they weren’t following it.”

Fisher responded to concerns about continuous testing in quarantine by stating that in accordance with CDC guidelines, students are held in isolation for 14 days regardless of “whatever repeated tests might reveal” and that “testing is not changing the isolation.”

“If they were tested around five days after their exposure—which is what [USF SHS] tries to do, I believe—this would maximize the chance of them testing positive and needing further medical supervision,” Fisher said. “If the student tests positive later in the isolation period, it would not be something we’d need to follow for tracing as they had been isolated for more than 48 hours prior to the test.”

Administrative Aid Going Forward

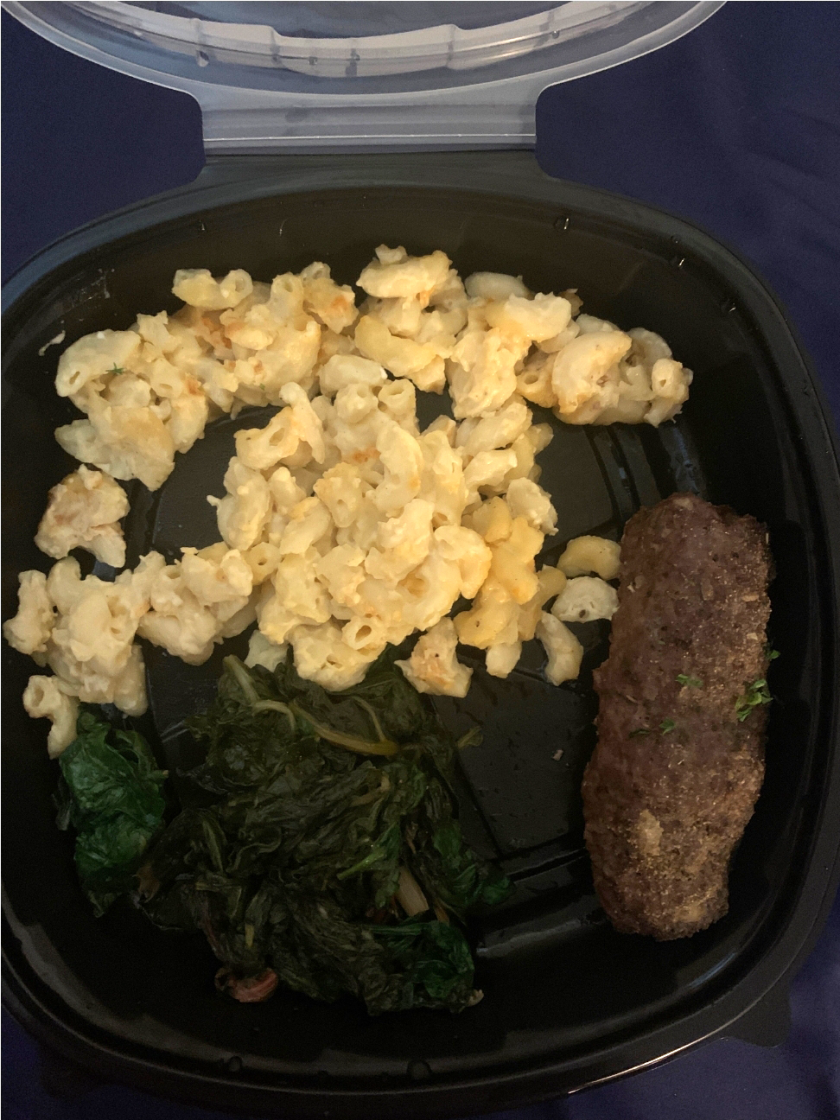

In the midst of the breakdown in communication experienced by quarantining students, New College was able to offer some support. For those quarantining on campus, Gelfert served as a physical point of contact for students by delivering their food to their dorms from Metz Culinary Management, and was able to offer solutions to some of their complaints. Zelznak, for example, asked to stop being served three meals a day to reduce how much they were being charged.

“I didn’t want to be paying for three meals a day that I wasn’t eating,” Zelznak said. “I told her [Gelfert], so I stopped getting lunches. She eventually spoke to the people in Ham and was able to get me a menu where I could circle things that I wanted for certain days.”

Zelznak said that when it came to their meals in quarantine, “breakfast was the safest, dinner was okay and lunch was garbage.”

Zelznak claims that they do not recall getting a single meal while it was still warm.

Zelznak took photos of many of the meals that they did not eat, and eventually asked Gelfert to stop serving them lunches altogether.

It is unclear whether all students quarantining on campus will be provided menus from now on or if Zelznak was an exception after having issued a complaint. Similarly, after Casey lost all Wi-Fi connection and cell service except for one specific spot in his bathroom, Gelfert provided him with an ethernet cable and even offered to move him to a new room.

“[Lack of Wi-Fi is] definitely a major problem with the Pei dorms, and I’ve heard that from everyone who has lived there,” Casey said. “But even then, [if] they’re going to move me to another dorm [then] what’s the chance that I’ll have Wi-Fi there?”

Zelznak was also offered counseling by the CWC and Tinsley was referred to the Student Success Center (SSC) by a professor while in quarantine as means of additional aid. However, both were critical of how helpful these services were when they were already struggling with Wi-Fi issues and a lack of information in other areas.

“What is getting on another video call with the CWC counselor going to do for me?” Zelznak asked. “What’s going to help me is you copiously and coherently telling me when and how I get out.”

“Is this really going to help me to have another Zoom call that I’ll have to schedule in addition to my Zoom classes and my telehealth appointments?” Tinsley continued. “What exactly is this supposed to do for me here?”

Even the end of each student’s quarantine brought one final obstacle: negotiating release dates. All seven students entered quarantine on Oct. 13 and should have been released on Oct. 27 according to the prescribed two-week isolation period. Even so, Lough said that he was originally told that he would only need to quarantine for 10 days, which was later bumped to the recommended 14. By the end, he was kept in quarantine until Oct. 28 due to a telehealth scheduling error. Zelznak was also given multiple conflicting release dates throughout their quarantine.

“It was just very troubling that they weren’t able to just give us a date earlier on,” Zelznak said. “A cohesive date [that] we could have looked at and been like, ‘This is the day we’re getting out,’ and not have that troubling sense that we’re going to be locked in here for another however-long.”

Edmonds has since returned from Tallahassee and settled back into her dorm. Now that her quarantine and those of her roommates and friends has ended, she asked that New College faculty and administration exercise more compassion for students quarantining both on and off campus. Both because of the challenges and confusions of negotiating with multiple parties that suffer their own miscommunications, and also because of external challenges New College students are facing in these unprecedented times.

“How can they [expect us to] isolate and have a change in environment [and have] their workload be normal and just not care?” Edmonds asked. “[Having to say,] ‘Hey, we were just in isolation. Please give me an extension.’ It’s just frustrating.”