Something that is rarely discussed about the New College undergraduate experience—although perhaps it is universally understood—is that time is never quite on our side. Many students have lofty ideas of clubs and organizations they could kickstart, issues they wish to advocate for and change on campus that they want to effect, but that fade away into obscurity once they graduate with no one to take the helm. With an often-rotating faculty, staff and a host of interim positions, some leadership roles on campus are or have remained in limbo as a proper replacement is sought for. And whereas a sense of community history is arguably lost or buried, New College campus is also entrenched in a very different kind of history: one defined by its land and the buildings occupying it. Amidst a sea of ever-changing faces, buildings like the Pei Residence halls and College Hall with their historic, architectural legacies loom over them.

But these buildings are not immune to the passage of time either, and recent renovations of spaces on campus—noticeably the Caples Mansion—call to attention those lost pieces of New College history, what is still the same and what continues to change. With Emeritus Professor of Literature Arthur “Mac” Miller playing the role of tour guide, the Catalyst invites you to join us for a seance of the Ghost of Caples Hall, a glimpse at early student and campus police relations, the life and times of the New CollAge magazine and much more.

Miller joined the New College faculty in 1964 at 27 years old, the youngest member at that time. Prior to his arrival, he was an undergraduate of Princeton University who then taught part-time at several colleges before attending graduate school at Duke University, and finally, serving in the U.S. Army.

“I came right off of two years of active duty with the Army and back down to New College, which I found out about in a Denver, CO post, an editorial about the wonderful New College which was only 45 minutes from my home here in Ruskin, FL,” Miller said. “So I thought, I’ll take some leave and come down and check it out.”

“I came in 1964 to New College and never left, until I got so old and mean, they had to throw me out for being 65,” Miller later continued.

Miller retired approximately 17 years ago in 2005, and spent a total of 41 years at New College. He explained that, much like today, New College was made up of three core programs when he arrived—Natural Sciences, Social Sciences and Humanities. However, more in line with a traditional university, first-year students would all take the same three core courses, along with several supplementary optional courses for students to fill their schedules with.

This academic system evidently did not last, and Miller explained that these original core programs are now defunct.

“The Humanities division and core program, that lasted at least 12 years or longer, and the other programs in the Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences kind of fell apart due to the relative frigidity of their individual disciplines,” Miller elaborated.

In 1964, the only property that New College formally owned was the Bayfront Property. What is now Caples Campus was bequeathed to the college by Ellen Caples in 1962. According to Miller, the property had initially belonged to Princeton University—only loosely, however, as Mrs. Caples was still alive and living in Caples Mansion—but that New College had had its eye on the land for some time, and initially planned to convert the mansion into the President’s residence.

The college was able to acquire what is now the Residential Campus through a 99-year lease arranged with the Sarasota Bradenton International Airport, but Miller noted that this was “not a feasible relationship, as they say in real estate,” and so the college was looking to expand further.

“New College became interested in Caples Hall and made a deal with Princeton, part of which at the time was that the building had to be used for educational purposes,” Miller said. “Since it was relatively isolated from the main axis of the campus—this is before the fine arts buildings were built on the south side of the museum—it was used for faculty or program offices.”

Miller states the New College’s first ever Environmental Studies program office was in Caples Mansion, before his own office was moved to that location.

“My first office was in the basement of College Hall, underneath the U-joint of the men’s toilet, directly above my desk, which leaked,” Miller joked. “So I was very glad to move into Caples. I stayed there for years and years, on the second floor, the big central room which looks out over the bay to the west and has that little crumbling balcony to the east. That was a lovely place to be because I had lots of room for my books. I had a bright purple bathroom all to myself on the second floor, and very good company with the other faculty members.”

Classes were also taught in Caples Mansion in those early days alongside hosting faculty offices, with Miller himself holding senior thesis tutorials there.

While more contemporary New College orientation ghost tours may no longer tell the tale of the Ghost of Caples Hall, this story once ran rampant through the New College community, one that Miller has an insider perspective on.

To set the stage: Caples Mansion did not receive any renovations after being acquired by New College—”it was pretty much the way that it was left by the family.” The wooden floorboards on the second floor would—as they were north-south aligned—expand throughout the day and contract after sundown, one at a time, creating the audio-illusion of footsteps. What’s more, while Caples Mansion did not have mold at this time, it did have mice, which would create additional seemingly unexplainable sounds at odd hours. Miller bore witness to all of this through a handful of nights spent sleeping over in his office.

“I was something of a night owl in those days,” Miller explained. “Instead of driving 45 minutes back to Ruskin, I would sleep in the office until the next day because I’d get about three or four hours more of work done. I would always call up the campus cops and say, ‘Look, I’m working late in my office, don’t bother me. If you see a light on it’s just me, here’s my phone number, call me if you have any questions.’ And they would always honor that and not bother me.”

Campus security at this time was composed primarily of retired New York City cops, “which is absolutely marvelous because as you probably imagine, a New York City cop has seen every damn thing there is,” Miller commented. “And is not going to run around busting students for trivial infractions.”

A sect of the campus police were also Irish American—with a proclivity towards the supernatural and folklore—and would often make conversation with students. However, creaky floorboards aside, rumors about Caples Mansion’s supposed dark history had already been afoot.

“I was pretty well-acquainted with the cracking that sounded like footsteps,” Miller continued. “But the college police were not. Nor were they acquainted with the mice or the peculiar aspects of Caples architecture which included—I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it—that barred iron room on the second floor.”

The room attached to this barred window—which Miller theorizes was either used for storage or as a wine closet—inspired students to invent and circulate a story about how the room housed Mrs. Caples’ developmentally disabled daughter who she had locked away. The fictitious daughter was then said to haunt the Mansion after dying tragically in that room.

The pre-existing rumor mill, the superstitious campus police and architectural inconsistencies of Caples Mansion made for the perfect storm, and for an incredible story. One evening when Miller was working late in Caples Hall, per usual, he heard a frantic telephone call from the first-floor emergency phone. It was one of the Irish American campus police officers, calling to recount a terrifying tale. He was investigating the Mansion after hearing footsteps on the second floor, when he began hearing the upright piano kept in the northwestern room being played behind a locked door. Upon unlocking the door only to find the room empty, he left the building immediately.

“He was scared to death and he was going to call his wife and tell her that he was coming home immediately,” Miller said with a laugh. “He notified everyone that he was leaving the building. He was so frightened by this that I couldn’t persuade him that what he was hearing was the Mouse of Caples Hall running over the keys or probably the strings of the upright piano, and that the walking was merely a contraction of the building, and that the dead daughter being imprisoned was indeed just a story.“

“Before I retired, my oldest daughter—who is now a librarian over in Central Florida and also a New College graduate—she and I would lead tours from time to time of the building and point out all of its fabulous supernatural features,” Miller continued. “It’s amazing how these things persist. Buildings have history, and there were ghosts about Princeton when I was there, and ghost stories about Duke when I was there. It’s really one of the fun things about the undergraduate experience, the imaginative power of the supernatural.”

The aforementioned oldest daughter is not the only Miller alum of New College—former Catalyst Managing Editor Kylie “Ky” Miller (‘21) is also Miller’s daughter, and also not the only member of the Miller family with a history of student publication and editing.

Miller described the early faculty at New College as split into two categories: people who did stuff—the Natural Sciences, conducting experiments with tangible data—and people who talked about stuff—the Humanities, lecturing and discussing theories. However, this approach to Humanities as a hands-off practice did not seem helpful to Miller at all.

“In terms of teaching literature, it struck me that the experience of the Natural Sciences is very relevant to the study of literature, and in particular, the study of poetry,” Miller said. “In other words, one learns by doing, as distinct from learning by being talked at.”

The result of this is that Miller began having his students perform literary and poetic “experiments” as part of his courses, working with different techniques and formatting styles. Miller noted that the student poetry produced from these experiments was “at least as interesting and compelling as three-quarters of the stuff I was reading in little magazines”—tiny periodicals devoted to avant-garde and non-commercial writing. Thus, New College’s first ever student-run literary magazine was launched, with Miller acting as Editor in Chief: the New CollAge magazine.

“These were the days of the so-called mimeograph revolution,” Miller said. “You could put out a magazine of anywhere between 50 and 500 copies for just about the cost of the paper. It sort of grew up so that students who were interested in it could participate in a rather extensive editorial board, and sometimes we’d get as many as a couple hundred poems a week at the peak of the thing.”

Miller managed New CollAge for approximately 30 years, up until his retirement. The magazine featured student poetry and visual art, as well as submissions from the Sarasota-Bradenton community. New CollAge was run primarily by student volunteers, and funded through the combination of a subscription service and New College Student Alliance (NCSA) funding.

“The idea was to stay away from funding by the college, mainly for two reasons,” Miller elaborated. “Number one, prior to 1975 when we were taken over by the University of South Florida (USF), fundraising was very fragile and many of the people in Sarasota who were donating to the college were quite sensitive to, shall we say, colorful language and opinions. So rather than indulge in some paroxysm of self-censorship in order to keep the New College Foundation happy, I decided that we would simply go at it as an independent student-supported entity as distinct from a college-supported entity.”

“That’s where the main difference is between, say, the New Music New College (NMNC) program and New CollAge,” Miller continued. “That may have been a mistake, because New CollAge did not persist past my retirement and the NMNC program has persisted past Steve Miles’ point of retirement.”

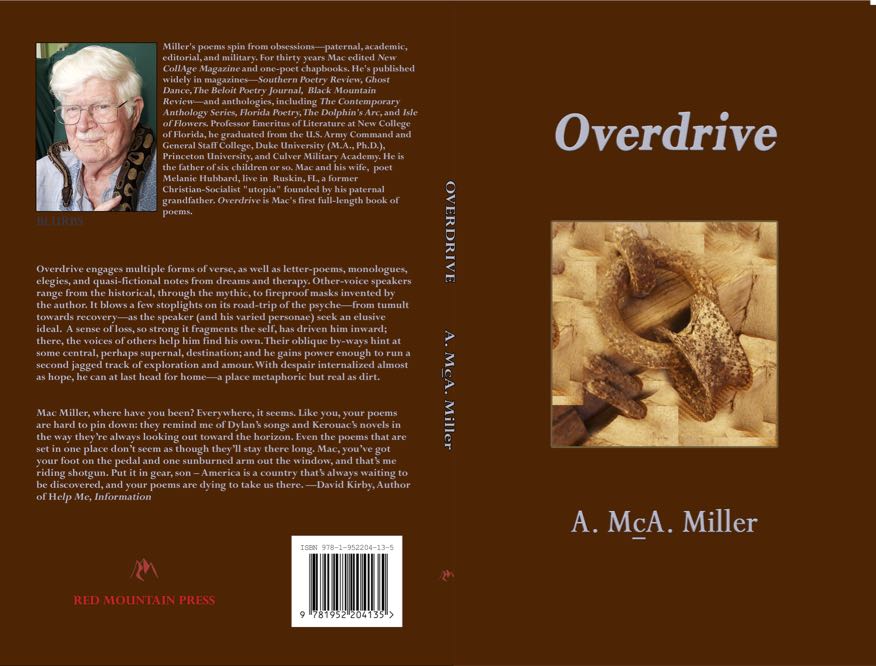

“That was a lot of fun,” Miller said, reminiscing on the days of New CollAge. “So over the years I began to gather some momentum and for me, writing verse was at first a pedagogical experiment, and then secondly as when one drives through the crisis of middle age, composition became sort of a life raft.”Although New CollAge is no longer in circulation, Miller’s own poetic endeavors have come to a peak in his retirement. While Miller had previously published his work in anthologies and little magazines, his first poetry collection, Overdrive, was just released in Feb. 2022. Miller added that the book was compiled and edited by two other New College alumni and students of his, Lance Newman (‘86) and J. P. White (‘74).

So much of New College continues to evolve, or at least attempt evolution, just as much as it continues to stay the same. As its community members fight both for change on campus, and for ways to cement themselves in its history, to continue to effect change once they are gone. As, arguably, one of those community members whose influence is still felt at New College, Miller offered some parting words of advice:

“I would think that New College is now an endangered institution, academically, because of its creeping requirementalism and its continuous quantification of things that are not susceptible other than to quality assessment, not quantitative assessment. We’re being driven by a number of state-wide metrics of our not-too-enlightened legislature to crack out numbers of widgets from the assembly line, the widgets in this case being called students. So we have to be very careful that bureaucracy—that, necessarily, one must have to interface for the large state system—does not overwhelm the educational mission.”

I love the statement that NCF is both struggling to evolve and stay the same. What will win? a combination somehow of both?