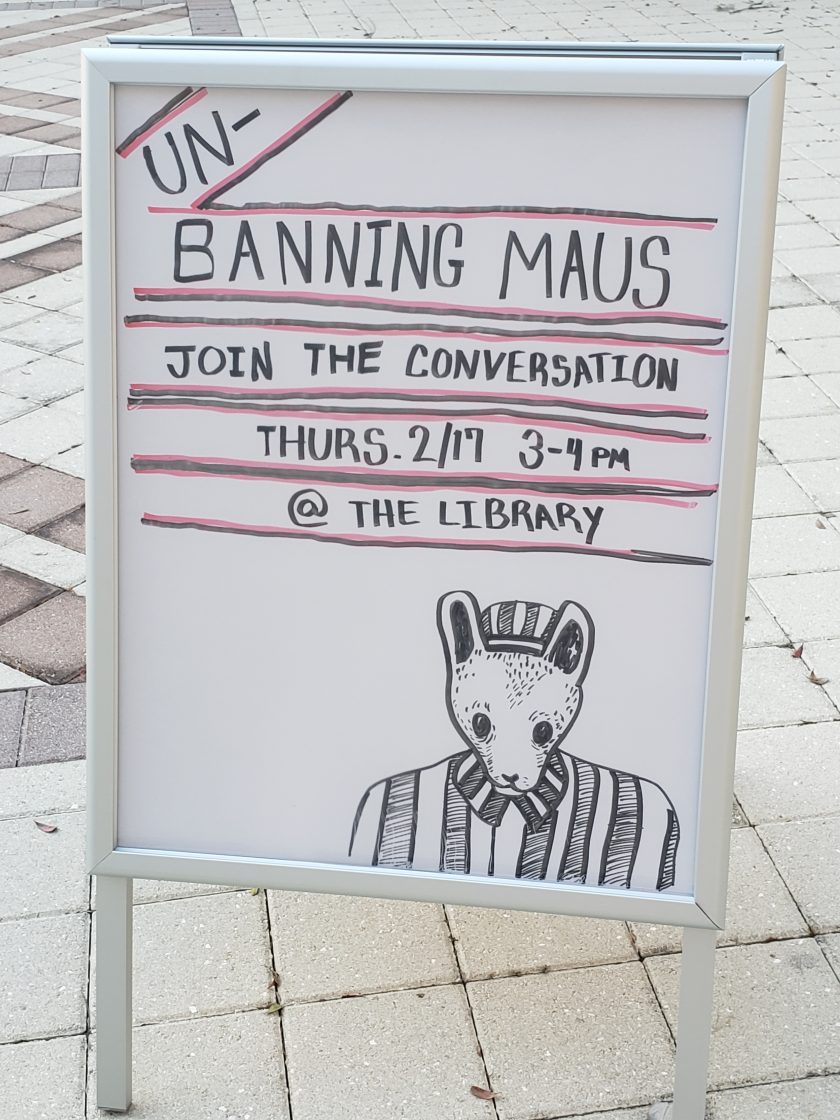

On Jan. 10, approximately two weeks before Holocaust Memorial day, the McMinn Country School Board in Tennessee unanimously voted to ban Art Speigelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus. As part of what some have identified as a larger effort to censor books dealing with critical race theory, student protestors have responded with the mass distribution of Maus—as well as the also recently-banned Beloved by Toni Morrision—in districts across Texas and Virginia. Here at New College, Assistant Professor of English Jessica Young in collaboration with the Jane Bancroft Cook Library organized their own form of protest on Feb. 17 with the “Unbanning Maus” event, introducing students and faculty to the novel’s nuanced approach to Holocaust testimony in a world of continued book censorship.

Maus is a nonfiction graphic novel and autobiography that tell the story of Speigelman’s father, Vladek, as a Holocaust and Auschwitz survivor, in which Jewish people are portrayed as mice, Nazis as cats and various other nationalities as other animals.

“It’s about survival, and then also about the relationship that Art has with his father and the difficult relationship that the generation after the Holocaust has with Holocaust survivors,” Young said.

Young first encountered Maus in college, when it was the only graphic autobiography of its time, and has held onto those same copies ever since. She describes Maus as having been a game-changer, something that both redefined the capabilities of graphic novels as an art form, as well as foregrounding a new kind of second-generation experience of the genocide.

“[Maus] reached a mass market commercial viability that only really popular DC and Marvel comics had,” Young explained. “It sort of changed the circulation of comics, the way we talked about comics. [It is] still the only comic that has ever received a Pulitzer Prize. It’s really an important book in both comics, and also in Holocaust storytelling and testimonies about the Holocaust.”

Maus was banned in McMinn county schools due to violence, profanity and nudity, according to the McMinn County Board of Education meeting minutes.

“I am not denying it was horrible, brutal and cruel,” board member Tony Allman said, referring to the Holocaust. “It’s like when you’re watching TV and a cuss word or nude scene comes on, it would be the same movie without it.”

“We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history,” board member Mike Cochran later continued. “We can teach them history and we can teach them graphic history. We can tell them exactly what happened, but we don’t need all the nakedness and all the other stuff.”

Young went on to comment that the profanity referenced by the McMinn County Board was the phrase “God damn,” and later at the “Unbanning Maus” event called this verdict a “troubling misreading.”

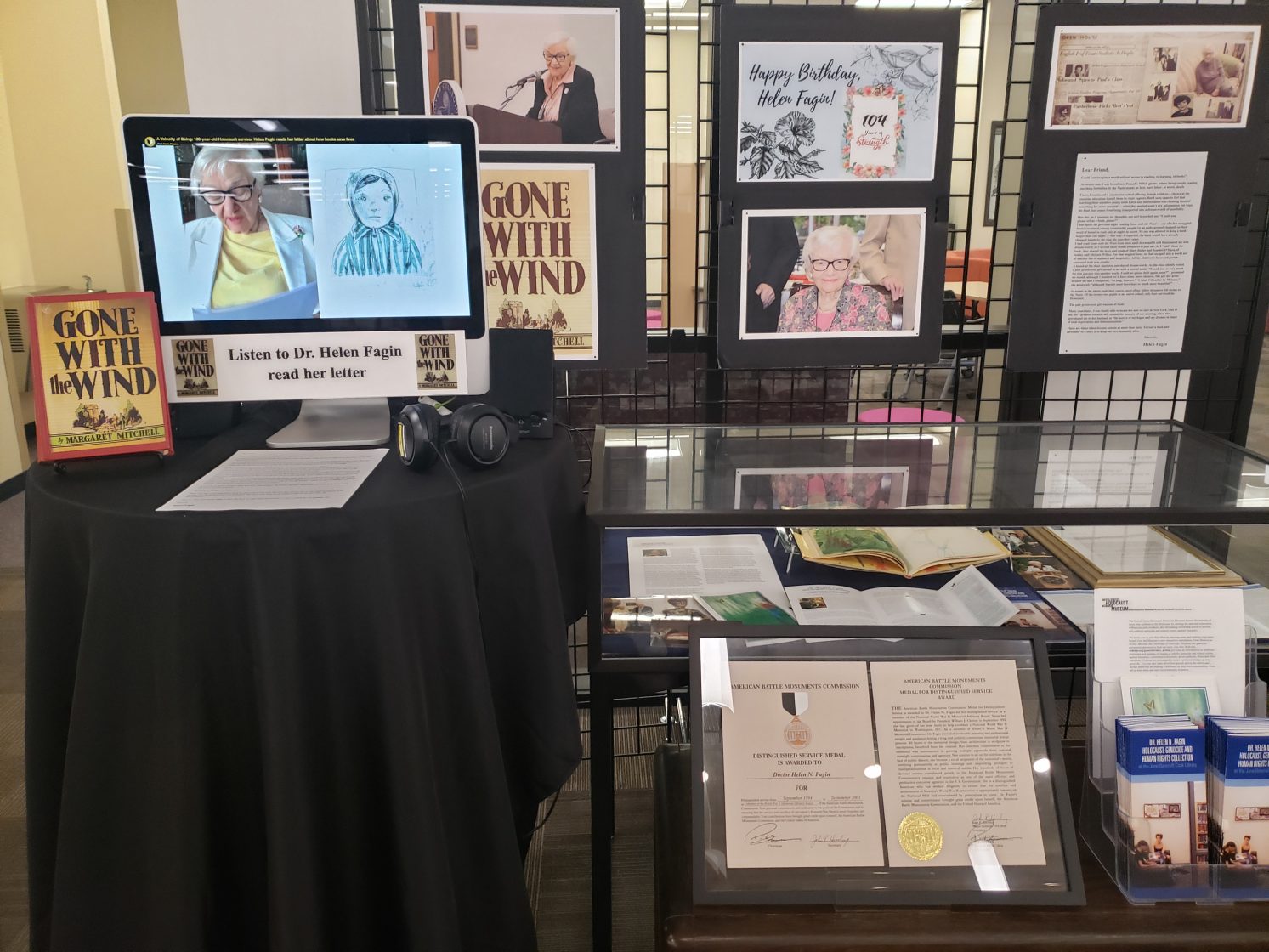

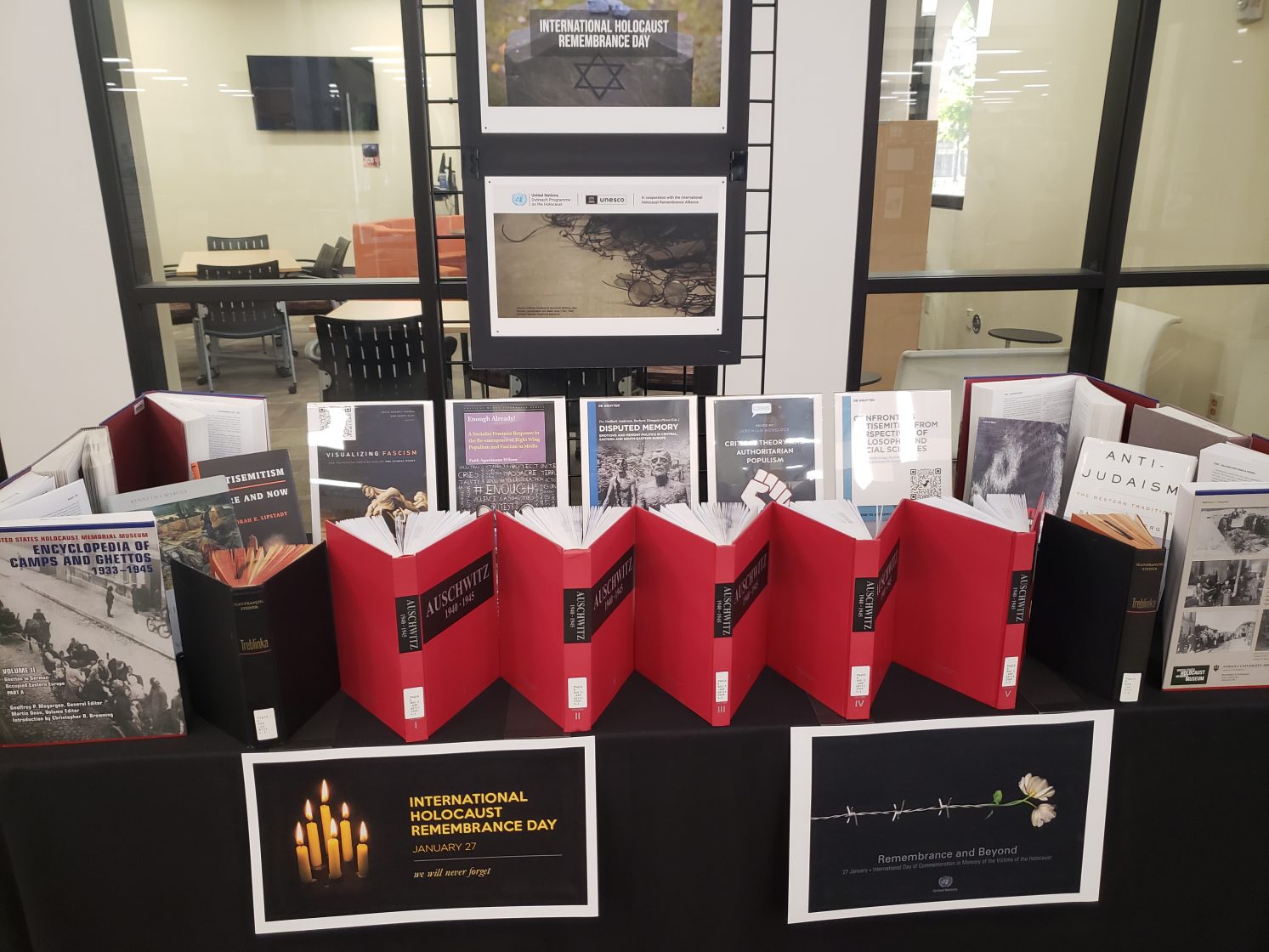

The event was hosted in order to facilitate discussion following a group reading of several selected pages of Maus, as well as a brief lecture by Judith Fagin, daughter of Dr. Helen Fagin, for whom the library’s Dr. Helen N. Fagin room is named for. A Holocaust survivor herself, New College established the Dr. Helen N. Fagin Holocaust, Genocide and Human Rights Collection in 2008. A Holocaust Memorial exhibit featuring video and audio of Dr. Fagin currently sits in front of the Col-Lab.

Fagin prefaced the group reading with a letter written by her mother, recalling when she was 21 and forced into a Poland ghetto during World War II where books were forbidden. Dr. Fagin would retell stories from books that had been smuggled into the ghetto to the young children being held prisoner with her, only four out of 22 which survived.

“There are times when dreams sustain us more than facts,” Dr. Fagin wrote. “To read a book and surrender to a story is to keep our very humanity alive.”

“Banning books is nothing new,” Young said, echoing Dr. Fagin’s experiences. “It’s something that’s been happening for a very long time. And I think it does young people, especially, an extreme disservice, for telling them what they can and cannot read. Because I think books, even if they are difficult, ask us to inhabit different worlds than what we might usually experience. And that’s only through inhabiting other people’s worlds, other people’s worlds, other people’s perspectives, that I think we can build empathy and create a better world.”

When asked why students should read Maus, Young responded with a laugh, “Mainly because they’re telling you not to.”

“There really is something about reading literature that makes you uncomfortable, and sort of confronts who we are as humans and doesn’t try to sugarcoat or give us some sort of redemptive reading of something as horrific as the Holocaust,” Young elaborated. “There is value in being confronted and being made uncomfortable, even if you are surrounded by cute cartoon mice and cats and things like that. There is something important there that can teach us something very valuable about history, about our current political moment and about where we should go as people.”