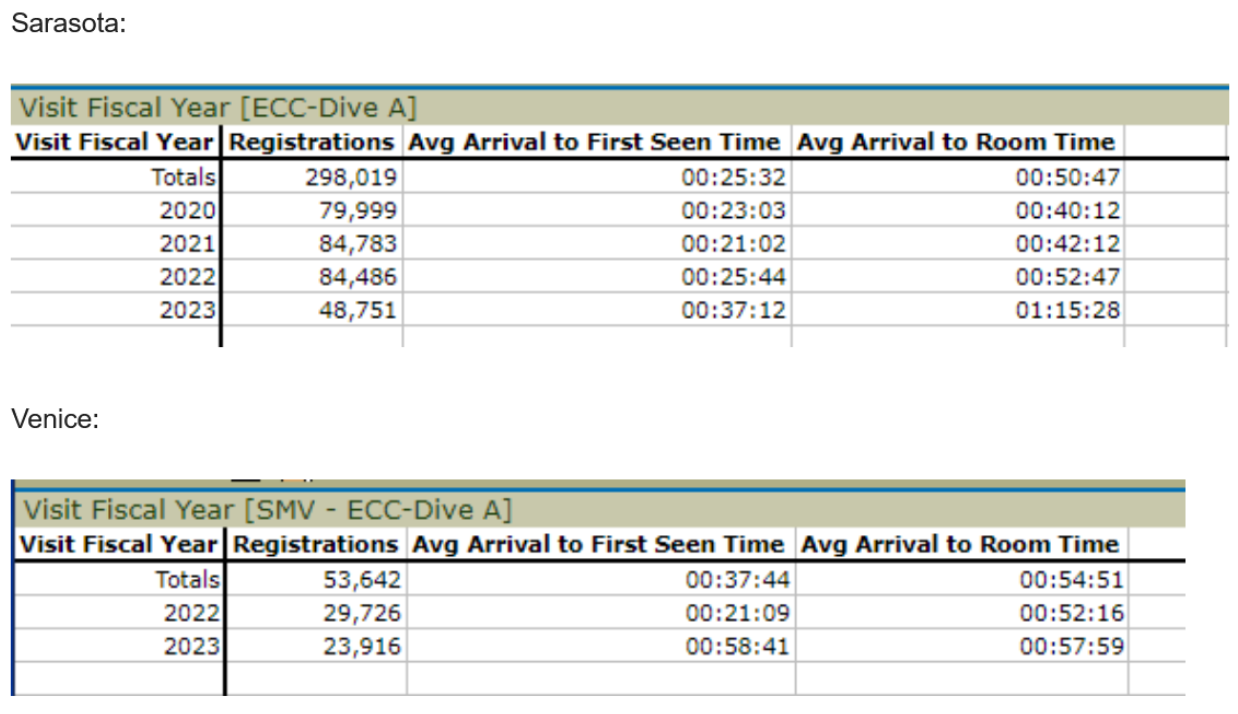

Anyone in the Sarasota area who has recently made a visit to an emergency department or spoken to healthcare professionals knows that emergency departments have been under strain. Yet, this year hit the region particularly hard. Investigative reporting by the Catalyst has revealed that the wait times at the Sarasota Memorial Hospital (SMH) have increased by 45% since 2022, and wait times at the SMH Venice campus (SMH-V) have increased by over 250%.

“This is the worst I’ve ever seen,” one hospital worker at the SMH told the Catalyst. “The coronavirus pandemic was nothing in comparison.”

Emergency department overcrowding is a serious issue for healthcare outcomes. Research indicates that such overcrowding leads to patient discomfort, reduced privacy, treatment delays and a higher risk of prolonged disease and death. It also leads to more violence against staff, greater clinician and nurse turnover and higher rates of burnout. When hospital staff are overburdened, a cascade of negative effects often butterflies into other areas of the healthcare system while patient outcomes worsen.

The Sarasota region healthcare system in particular may now be experiencing historic levels of pressure. Besides longer average times to be seen by a healthcare worker after arrival, the average time to receive a bed after arrival has also increased. According to reports directly shared by SMH hospital officials from their internal system, the time to receive a bed at SMH has increased by 43% since 2022. At the SMH-V facility, the time to receive a bed increased by 10%, with many patients waiting in hallways before being diverted by ambulance to the SMH facility in Sarasota.

“Emergency room wait times across the country have definitely increased to a level that I personally have not seen before in my career,” Director of Patient Care Services at SMH-V Lisa Collins-Brown, who has also been working in hospital care for decades, shared in an interview.

“It’s been a lot of highs and lows,” Collins-Brown continued. “There was one point during [COVID-19] where we were overwhelmed. And then you turn around and have almost no volume, and we had to have people voluntarily stay at home and not work because the volume had gone down like 50%. We had that big campaign nationally where ERs were saying, ‘Stay home, protect us.’”

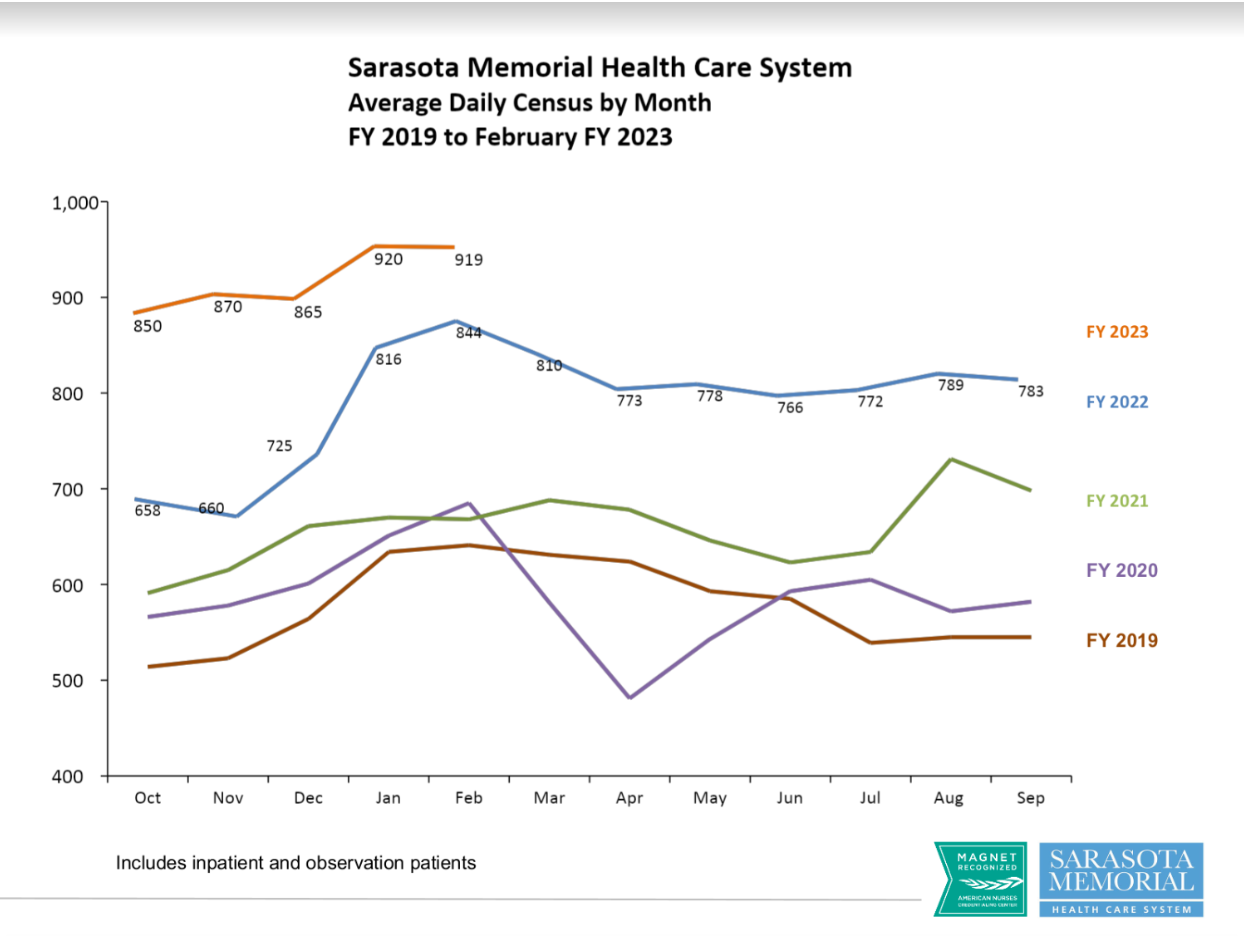

The raw numbers seem to support this claim. According to the data directly provided by SMH hospital officials, the average daily volume of patients at SMH was comparable in 2019, 2020 and 2021, with a notable reduction in volume at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Then, in 2022, there was suddenly a surge of new patients. The average daily volume at SMH in January 2021 jumped from around 650 to 816 in 2022. Then, in 2023, the average daily volume jumped again to 920, an over 40% increase since 2021.

These changes aren’t unique to the publicly-owned SMH either. Hospital executives from the Health Corporation of America (HCA) Doctors Hospital in Sarasota—HCA being the largest private healthcare company in the United States that operates one in six Florida hospitals—and the privatized Manatee Memorial Hospital in Bradenton corroborated that the system has been under pressure as of late, although they declined to share specific numbers.

This is in the context of overcrowding and long emergency department wait times plaguing the healthcare system more broadly for decades. In 2007, the Institute of Medicine reported that hospital-based emergency care was at a breaking point in the U.S., with 90% of emergency departments noting extreme stress at some point during the year. The number of emergency department visits has increased by 50% from around 100 million to 150 million since 1999, while inpatient capacity has decreased by over 25% in the last ten years.

When the Catalyst asked hospital officials throughout the region what the driving force for increased wait times this year was, the most prominent answer was the closing of the ShorePoint Health Venice hospital last September after Hurricane Ian swept through Florida.

“The hospitals to the south of us either had to close or were unable to take patients because of the damage that they had, so we felt the impact of that,” Collins-Brown shared.

The closing of the hospital in Venice is far from the only factor, however. Hospital officials pointed to a broad spectrum of problems that have exacerbated the issue. For them, key pressure points included things like population growth outstripping current resources; the prevalence of baby boomers who are reaching their sundown years and require longer and more urgent care; the presence of snowbirds—a colloquialism for residents from northern states who come to Florida during the winter months—who don’t have primary care physicians; a lack of primary care physicians more generally; and the presence of uninsured Floridians who come to the hospital when they are denied care at other offices.

When asked whether a shortage of healthcare workers was contributing to the issue, hospital officials were generally adamant that staff shortages were not responsible and that hospitals were adequately staffed most of the time.

Yet, when the Catalyst talked to nurse and member of the 1199SEIU healthcare union Loretta Blauvelt, who has worked at private hospitals throughout Southwest Florida, a different story was told. According to Blauvelt, systemic understaffing and poor worker treatment are huge contributors to poor patient outcomes.

“If the whole hospital’s open, you still have skeletal staff,” Blauvelt said. “We had skeletal staffing before the pandemic. It was when COVID-19 hit that it exposed how vulnerable our healthcare system is. I know one of my hospitals has a closed unit and went ahead and still had lines in the ER. It was about the staffing, not about the patient. And the people that are paid to implement those staffing ratios… They don’t come into the hospital. They don’t walk the halls. They don’t see the floors that can’t get mopped.”

When asked whether there were enough resources for hospitals to address these issues, Blauvelt responded in this way:

“These big healthcare corporations do have the money,” Blauvelt said. “HCA made $13 billion in profit over the last two years. Almost half of that money, almost 40% of it, comes out of our Medicare and Medicaid tax dollars. Why so much of our money? Why is it all going into their shareholders’ pockets? Giant companies like this need to be putting more of these resources into patient care. Healthcare should be about the quality of care for patients, not huge profits first.”

Research conducted at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business in 2019 seems to support Blauvelt’s assessment. According to researchers, most hospital waiting times persist even after having enough staff and resources on average. They concluded that this is because there is no financial incentive for healthcare providers to invest resources towards strategies that lower wait times when the compensation they receive through Medicaid and other systems is based on treatment only.

While profit maximization at hospitals may lead to a trend of long wait times during low-volume periods, most research leaves no doubt that the main contributor to long wait times during high-volume periods is a lack of capacity.

In particular, research suggests that no system involving the rotation of persons through a building should ever be higher than 85% occupancy for operational breathing room. When hospital occupancy topped over 85% during the coronavirus pandemic between January 2020 and December 2021, boarding times exceeded six and a half hours, compared to around two and half hours when hospitals were less crowded.

According to healthcare workers throughout the area, one’s wait time is also correlated to a number of other factors, including the condition that one arrives in. It also depends on what time of day you arrive. Late at night and early in the morning are usually the quickest times. But if someone arrives midday seeking treatment for a medical emergency, as most people do, they would likely be in for a grueling wait as the system lurches and groans under the pressure of a completely full queue.

Monday is almost always the most crowded day, as folks who couldn’t see a doctor over the weekend are seeking immediate attention at the hospital. Yet, if you are having a medical emergency, you don’t get to choose when you go.

Some of these regional pressures could be alleviated once the planned expansion of SMH is completed in 2024. Until then, the local system continues to be bottlenecked, burnt out and under rising levels of stress.