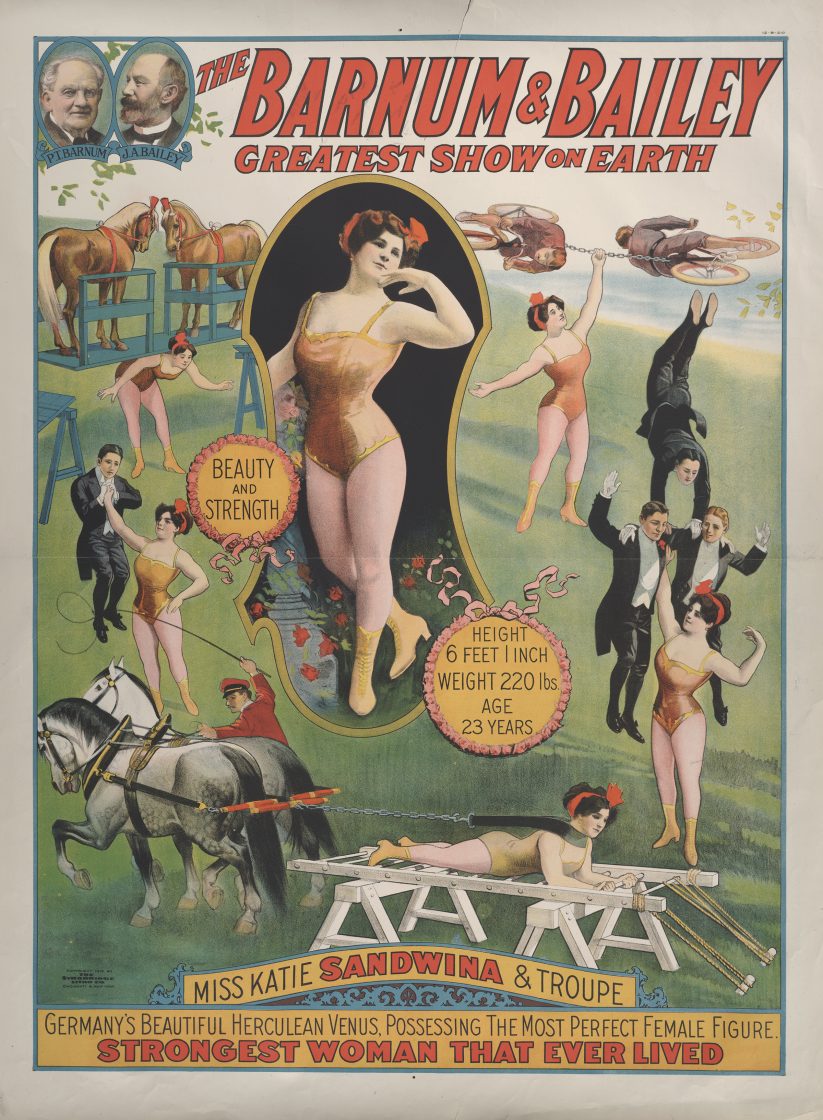

Barnum & Bailey, Miss Katie Sandwina, 1912

This August marked the 100 year anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which officially granted women’s right to vote. While the suffrage movement is widely associated with figures such as Susan B. Anthony and for events like the Seneca Falls Convention, the Ringling Museum aims to shine the spotlight on a lesser known piece of the puzzle: the roles that circus women played in the suffragist movement with the soon-to-open “Circus and Suffragists” exhibit.

The exhibit opens on Oct. 31 and runs until Feb. 14, 2021. It is free with museum admission—which is free for New College students who bring their student ID—and is located in the Circus Museum section of the grounds.

The “Circus and Suffragists” poster exhibition is being organized by Tibbals Curator of Circus and New College alum, Jennifer Lemmer Posey (‘98). Posey studied art history, but said her open-ended job title and the circus collection of over 25,000 objects—ranging from wardrobe pieces to an entire train car—lets her explore and showcase topics that go beyond baseline circus history.

“I see my primary responsibility as stewarding the collections and the stories that they represent,” Posey explained. “Making sure that they’re preserved for the future, but also working to make sure that they’re relevant and meaningful to today. It’s great to preserve history, but what does it mean if it doesn’t relate to our lives as they are?”

The exhibit is featured in the poster gallery and will primarily display printed materials related to circus advertising. The materials for this exhibit come from the Ringling Museum’s holdings of about 8,000 circus posters.

“[The] poster case is a small space, but it’s a really great, flexible place to tell these stories about where circus and culture interact,” Posey said.

Each exhibition typically begins when Posey has a topic she is interested in researching that can connect to other features of the museum, but she said “Circus and Suffragists” was organized at the request of a colleague to commemorate the anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment. The exhibition was originally supposed to open in June and run through Aug. 26, the exact date of the amendment’s ratification. However, concerns over maintaining a safe social distance while changing out and setting up the exhibit in the small poster case space—not to mention the recent string of staff layoffs—meant that the exhibit had to be postponed until Oct. 26. This date was pushed back further to Oct. 31 due to rescheduling to better accommodate for the exhibit exchange process. The last of the printed material arrived at the Ringling Museum on Oct. 22 and the exhibition was then installed on Oct. 26 and 27.

“‘Circus and Suffragists,’ this poor exhibition, has been so cursed from the very beginning,” Posey said with a laugh. “But it came up because there was an effort across Sarasota to honor the anniversary of suffrage, for all women across this country.”

New College Professor of History Brendan Goff offered some historical context to better understand what was impactful about the role of circus women in the suffragist movement. The early 1900s was dominated by maternalist politics and reforms, characterized by the idea of women as nurturers. The charge was led mainly by well-educated and well-traveled white women and came to a head during the 1916 election.

“Even though women [didn’t] formally have the right to vote at the federal level, there [were] various states that allowed women to vote long before the Nineteenth Amendment,” Goff clarified. “And in fact, Woodrow Wilson would not have won a second term in 1916 without women’s vote in Western states. The pop culture assumption is that before the Nineteenth Amendment, women didn’t have the right to vote, [but] it’s much more complex than that.”

Even so, maternalist ideas and what Goff identifies as the “cult of masculinity” running rampant at this time both culminated in events like the 1908 Supreme Court case of Muller v. Oregon that allowed the state to assign women less work hours than men. Overall, it caused the popular perception that women were the frailer sex and in need of some form of protection. The performances of circus women, however, challenged these ideas.

“The athleticism of the women in these circus acts is counterfactual to all of that,” Goff said. “This is not the softer, weaker sex. These are women who are engaging in these acts of athleticism over and over for a paying audience.”

The role of circus women in the suffragist movement, as well as in the “Circus an Suffragist” exhibit as a whole, brings back the sense of community and independence created by women performers according to Posey.

“Because of the women’s dressing tent, there were opportunities for women to talk together and to inform one another and build relationships,” Posey said. “Inherently, there’s always been a kind of women’s rights movement that’s underlying circus culture, but then there’s this very specific moment in 1912 which was what got my interest.”

This moment takes center stage in the exhibit: a 1912 meeting of the minds between the Barnum & Bailey suffrage group and leaders of the Women’s Political Union stationed in New York. This meeting represented a bridge between the educated women at the forefront of the suffragist movement and the circus women, whose athletic prowess was used to highlight the strength and endurance of the gender as a whole.

The exhibit will also cover specific women throughout circus history. One of the most notable is Josephine DeMott Robinson, a bareback equestrian and one of the frontrunners of the esteemed 1912 meeting. Posey cites DeMott specifically as an example of the empowerment the circus offered women: DeMott initially left the circus once she was married to build a new life amidst her husband’s political aspirations, but returned after coming to the conclusion that life outside of the circus did not offer her the same opportunities.

“She couldn’t take jobs she wanted to do, so she went back to the circus, which I think is just the best thing,” Posey said. “She had seen this world where she could make her own decisions, and the circus empowered her, so she went back to it. And at the same time, she became very active in her local suffrage group in New York.”

The Ringling Museum is offering free admission to New College students and maintaining safety regulations that require masks and limit groups to ten people. The “Circus and Suffragists” exhibition provides students with a socially distanced and educational event for anyone interested in history, art or the women’s movement over time.