by Jasmine Respess and Pariesa Young

A study authored, but not released, by Director of Data Science Patrick McDonald and several data science graduate students is making waves in the headlines and legislature. The study called into question the findings of a Sarasota Herald-Tribune report, which revealed that Florida judges unfairly sentence Black defendants to more time in jail than White defendants.

New College President Donal O’Shea decided to get McDonald involved in the research, because he believed that judges were being specifically targeted as biased, especially Judge Charles Williams, a Black man.

“There was something serious going on in there, but to blame the Black judges seemed to me to be just […] like an old story,” O’Shea said. “Whether you should assign that to judges is difficult and whether you should say the judges are biased is another thing.”

In sociological studies by professors at places such as Northwestern University, it has been proven that people of color face bias in the criminal justice system. Reporters from publications such as the Washington Post have used these findings to report that racial bias causes Black Americans to face greater challenges at every stage of the justice process.

When Black individuals are three times more likely to have their car searched by police, twice as likely to be arrested for drug possession and given sentences 10 percent longer than white counterparts, according to Slate, there is not much room for debate over whether racial bias occurs in the criminal justice system. Yet the debate over whether a judge, the foremost authority in the courtroom, plays a role in this bias still rages on.

Bias on the bench

The findings of the Herald-Tribune report specifically highlight the role that judges play in an implicitly biased system. By analyzing sentencing data from across Florida, the paper found that despite legislative mechanisms in place to ensure fairness and consistency in sentencing, Black defendants still spend more time behind bars and judges around the state vary in their verdicts on otherwise equivalent cases.

“No one has ever denied the bias in the criminal justice system that we found, but time and time again all we kept hearing was ‘It’s not me,’” Josh Salman, a Herald-Tribune investigative reporter who worked on the project, said. “The more we dug into it, the more we found that absurd.”

The report, entitled “Bias on the bench,” was the product of over a year’s work from the Herald-Tribune investigative team and was released over the course of a few days beginning Dec. 11, 2016. The report came to several conclusions about the state of sentencing in Florida, mainly highlighting that in general, Black defendants are sentenced to more time locked up than White defendants, when comparing cases that are similar except for race. The paper also reported that this disparity is affected by – among other factors – the judge who presides over the case.

The data used for the series came from the Offender Based Transaction Statistics (OBTS), which is compiled by state clerks of court, and Department of Corrections (DOC) data, which comes from the prison system. Herald-Tribune investigators analyzed documents from 2004 to 2016.

Calls for judicial oversight

The Herald-Tribune investigation precipitated a bill in the Florida Senate (SB 382) which would increase judicial oversight, creating a public database of judicial sentencing patterns which would be shared with the judges themselves and state officials, and reassign the cases of judges who show racial bias in their sentencing.

On March 3, McDonald assented to two of his preliminary findings to be used to combat SB 382. Lawmakers temporarily postponed voting on the bill on March 10, to allow for further discussion after pushback from judges across the state.

The bill was endorsed by the American Civil Liberties Union and Southern Poverty Law Center, but received criticism from judges and others who argue that it is not judges who hold the onus for patterns of racial injustice in the criminal justice system. The methodology and findings of the report which initiated the legislation have also been called into question.

Questioning intentions and conclusions

Day four of the investigation reported that Judge Charles Williams was reported to show significant racial bias in his sentencing. With a closer look at graphs of his sentencing patterns in the Herald-Tribune’s searchable database, Williams sentenced Black defendants who commit third-degree felonies for twice the time of White defendants. The opposite is true for first-degree felonies, where White defendants received higher sentences.

“Chiles appointed Williams to the bench in 1997 […] Since then, the 59-year-old has sentenced whites to an average of 1,060 days for robbery, according to data compiled by the Florida Department of Corrections,” the article said.

O’Shea, who has known Williams as a community member since the judge delivered a New College commencement address in 2013, was surprised to see Williams singled out in the Herald-Tribune report, especially since he knew of Williams history as a member of the community.

“It just seemed like an attack,” O’Shea said.

Williams, who left the bench in 2004, had only one year of data available for the Herald-Tribune investigation, however the article spoke of his sentencing patterns since he was appointed as the circuit’s first Black judge.

O’Shea did not think this was long enough for overarching conclusions to be made.

He does not believe the Herald-Tribune intentionally blamed Black judges for racial bias in the justice system, but that the article could have been misinterpreted to that end.

However, the paper wrote in their first article in the series that as a whole, “Blacks who wear the robe give more balanced punishments.”

A study published in the Southern California Law Review came to the conclusion that “minority judges tend to assess discrimination claims differently than white judges,” arguing that a judge’s race, among other demographic and social characteristics, does play a role in how they sentence.

Taking another look

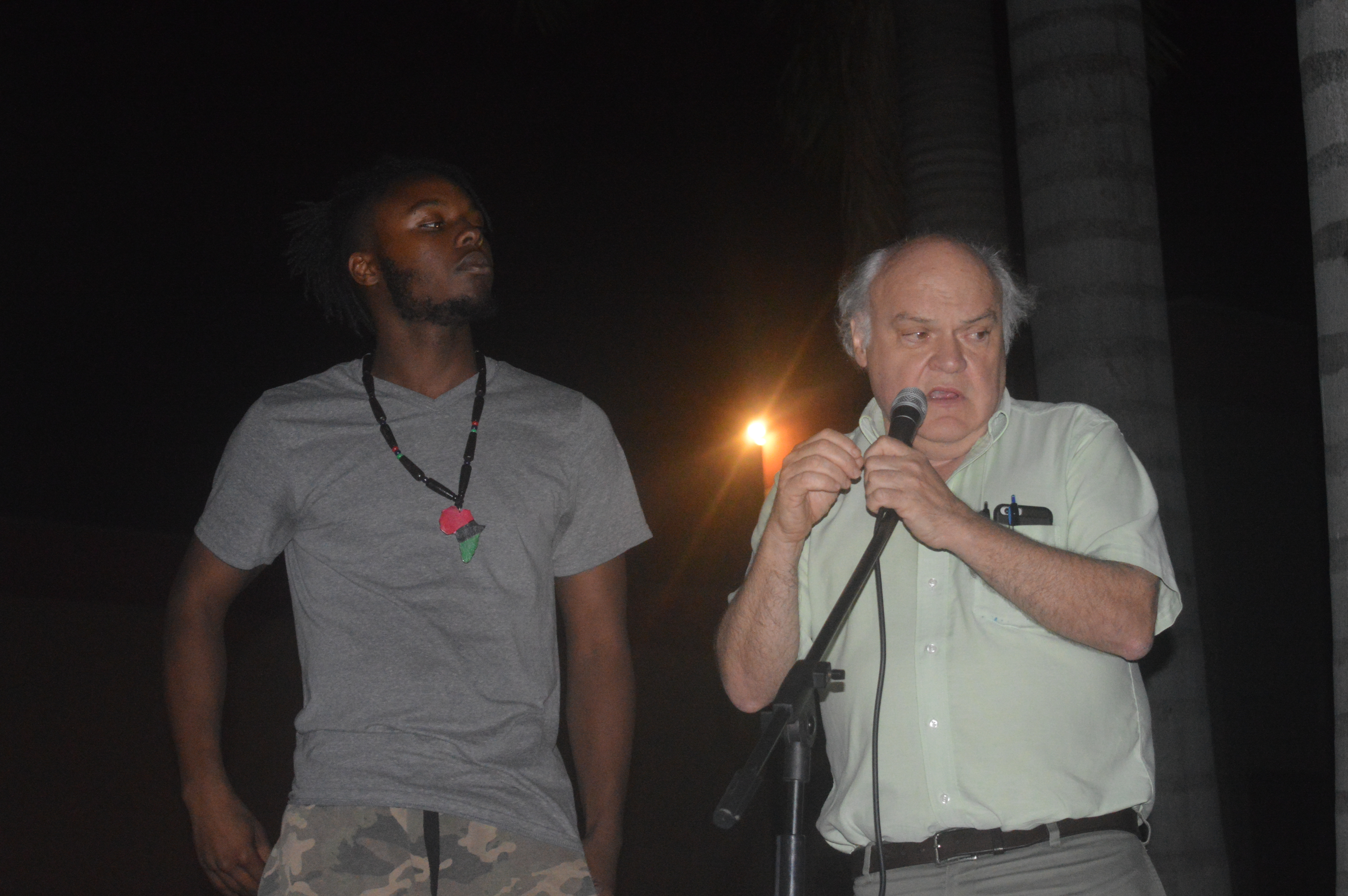

After reading an op-ed O’Shea had published in the Herald-Tribune, Judge Williams and his colleagues reached out to see if the college had the expertise to prove that the Herald-Tribune findings were misleading.

“I do think it’s important to speak out when somebody attacks a single member of the community,” O’Shea said. “The judges were delighted on the article.”

In an email acquired by the Herald Tribune dated Dec. 20, 2016, McDonald told O’Shea and several circuit judges that “we have the expertise to do the required analysis.”

However, in a statement to the Herald-Tribune, McDonald wrote, “I am a mathematician, not an expert in criminal justice.”

The Herald-Tribune spent over a year cleaning up their data, the coding for which required an inch-thick book. They consulted often with system administrators who compiled the data to ensure that their interpretations of complicated codes in the data reflected reality.

“It’s a really really complicated database,” Michael Braga, investigations editor at the paper, said. “Months and months of cleaning […] We feel sorry for Pat McDonald, because he had to do it in less than a month.”

The Herald-Tribune received a request from the 12th Circuit Court for access to the raw data they used, but the paper did not turn the database over, despite offering to go over their methodology, as well as sharing the codes used to run their analysis.

In a letter to Judge Williams signed by McDonald, the paper’s transparency was called into question. McDonald wrote that at minimum, the paper should have provided its raw data, software, code, a discussion of their interpretation and a measure of confidence in their findings.

“When the 12th Circuit originally approached [Herald-Tribune] for the data, they said ‘Can we have your data?’ and I said ‘It’s actually your data,’” Braga said. “They are the ones that type it in.”

The data used by the Herald-Tribune had all identifying information redacted, while the 12th Circuit keeps unmodified databases of information.

“I said to them, ‘Get it yourself, your data is better,’” Braga said. “They took that as me refusing to give them the data.”

McDonald worked with the court to file the same records requests that gave the Herald-Tribune access to OBTS data, however he did not use the DOC data in his report, as the OBTS numbers were the ones used to make the initial claims about Judge Williams, he said.

After gathering the data and coding it for analysis, McDonald worked with a group of 12 faculty and students to produce a report in under a week. A Herald-Tribune article titled “Judges defend role in sentencing with flawed study” published April 2, released both the 29-page preliminary report that McDonald had shared with judges and many emails between O’Shea, McDonald and staff from the 12th Circuit Court.

The back-and-forth

Once the Herald-Tribune investigative team gained access to the report authored by McDonald, it was clear to them that many errors had been made in the attempt to correct their work. They sent it to experts who agreed that the study rebutting their findings was flawed.

“It wasn’t a true effort to understand what was going on in the justice system,” Salman said. “It was just an effort to exonerate the judges.”

The study created a framework to analyze the sentencing patterns of only 12th Circuit Judges Williams and Lee Haworth, but was created with the intent for others to be able to replicate and change parts of the code to analyze any judge in the state.

McDonald’s report that was finished in March highlighted several aspects of the Herald-Tribune investigation which were considered a cause for concern; “failure to control for confounding by plea deals, failure to control for time dependent guidelines and sentencing norms, and failure to control for strong coupling of charges in the computation of aggregates.”

The most salient of these concerns, cited by Judge Williams, O’Shea and McDonald, was the inclusion of plea deals, through which the majority of sentencing occurs in circuits throughout Florida.

“I think a lot of the bias happens in the plea part,” O’Shea said. “I was appalled, because [Williams] had explained that only two percent of cases even go to trial.”

Plea deals come with recommended sentences, where judges may change or alter the sentence, or open sentences, where the judge is ultimately responsible for choosing the length of time a defendant will spend in jail or on probation. While some judges simply approve any legal plea that crosses their desk, others alter the offered plea based on their experience and professional opinion. Although the plea is presented by an attorney, judges still play a role in the final verdict and approve the final plea.

“We had reached out to numerous criminal justice and data experts who had done these types of studies before and they said ‘you absolutely include plea deals in your data analysis,’ so we did,” Investigations Reporter Emily Le Coz, who has worked on the Bias on the Bench series from the start, said.

Although New College, the 12th Circuit and Herald-Tribune are still at odds about the exact mechanisms causing bias in sentencing, there is no denying that the criminal justice system is biased against people of color.

“I think we should be honest and look at everything,” O’Shea said. “I think there is a bit of bias each way you go through [the criminal justice system.]”

O’Shea explained that cops, public defenders, prosecutors and judges are all responsible for what happens in court. They are all responsible for serving justice.

McDonald expressed a similar idea.

“In 30 years there has been a movement towards mass incarceration and the burden falls heavily on people of color,” McDonald said. “It is by design […] Lots of people contributed some consciously and some unconsciously. [A lot] rides on keeping the things the way they are. […] Changing it won’t be easy.”

Yet the jury is still out on how to research and remedy the racial bias. It is unclear whether lawmakers will move forward with SB 382 or propose further legislation to increase judicial oversight.

The complete Bias on the Bench series may be found at projects.heraldtribune.com/bias.

Information for this article was taken from heraldtribune.com, slate.com, washingtonpost.com, americanbarfoundation.org. www.americanbarfoundation.org/uploads/cms/documents/weinberg_nielsen_-_examining_empathy.pdf