Travel internationally amid the Covid-19 pandemic seems to be a challenging or even absurd idea. But it doesn’t mean that globalization is put to a halt altogether. Instead, we can travel with artifacts, in material and symbolic ways. Globalization is not an abstract concept: it is a process of embodiment that can be documented, witnessed and touched by all of us on a daily basis. In my “China, Africa, and Globalization” class, we set out on a journey of discovery. I asked my students to look for two artifacts from their own life that are relevant to either Africa or China and describe their encounters with these artifacts. They brought to class a wide variety of things, from African shea butter to Chinese cleavers, before discussing the impact of globalization upon their personal life. We are glad to share with the NCF community our kaleidoscopic collection capturing the surprising yet mundane manifestations of globalization.

—Yidong Gong, Assistant Professor of Anthropology

Jan Andersen: Cleaver

When I was first given a set of cleavers from a friend who thought I might make good use of them, the once sharp blades were tarnished and battered. The barely visible lettering on the knife stated their true identity. Chopping vegetables, slicing meat, or smashing garlic are all quick and efficient with this knife. The heavy weight of the handle and the ease with which the thin blade cut quickly made them one of my favorite knives. I began taking it to the restaurant I work at and found their all-purpose style suitable for any meal requiring efficiency. From soon to be discarded to a gift to ultimately ending up back in the market, as a tool for me to earn a wage, the cleavers like all objects are bound to the social relations between people that define their use.

The cleaver has a long history in China, dating back to their V-shaped precursors 4,500 years ago and coming into form as distinct knives depending on their use during the Tang dynasty with advances in iron-smelting. While my knives were styled after the Chinese cleaver, they were a product of the largest manufacturer of professional cutlery in the US, Dexter-Russell. The company started producing these knives for the large market of Chinese cooks in the US following large-scale immigration that culminated in a distinct form of Chinese cuisine that is among the most popular for people living in the US. While I take pleasure in using them, work as a cook can be very demanding and is rarely financially rewarding under our current exploitative economic model. Despite this, to see the bustle of the restaurant environment is a spectacle that can often be rewarding even under stress, after getting in a rhythm during a busy lunch rush or when after a long night of cooking, a collective sigh of relief signals the end of the workday and you wrap your knife in a towel to take home before sitting down for a drink with co-workers. It is in all of these relations that a cook’s knife becomes so important to him.

Hailey McGleam: Journal

My artifact is my journal that I took throughout my travels in primarily China but also in Japan. It begins with a list of all the things I wanted to eat, explore, and take part in various cities I thought I’d have the time to visit. Primarily, Nanjing, Beijing, and Shanghai. After that, it has a section dedicated to all the plane tickets, train tickets, and admission tickets from various attractions from cities all around China. Everything is labeled, dated, and ordered chronologically starting from my plane ticket from Chicago to Shanghai. It ends with my tickets to Japan while exploring Osaka, Nara, Kyoto, Tokyo, and back to Shanghai because soon afterwards the COVID-19 outbreak went global. Although I didn’t write about my experiences with COVID-19 in my journal, because I don’t think it represents my interactions with Chinese culture appropriately. Throughout the tickets I have comments everywhere and journal logs of my experiences. There are some drawings and poetry too. On top of that, I have a flower/plant leaf from every place that was significant to me. By now, they smell a bit earthy and have, unfortunately, started to lose their pigments.

The act of being able to share all the pictures with my American friends and family from when I was traveling shows how strong digital globalization is, especially when it comes to sharing one’s experiences with a large platform, creating an ability to shape others’ perceptions of foreign cultures. It gives a lot of power to people who have the ability to do this in terms of enforcing or disrupting assumptions made about other countries and their culture, since you can use visual/narrative information so freely. Yet, I am an aspect of globalization just as much as the people in China were for me. For example, the fascination of the locals with a foreigner and taking pictures of me despite not knowing much about it except that I’m different is perhaps why globalization is such an attractive concept: an experience with people, things, and ideas that are different from the experiences of daily life and routine.

Celeste Kadzis: Hand-stitched Tapestry and Jade Jewelry

An artifact, defined by the Oxford dictionary, is an object made by a human being. Artifacts can have significant personal connections and when they travel to different places around the world, they are connected to globalization. Globalization is the circulation of things, exchange of ideas, and movement of people. It is an ongoing, uneven, expanding process that has been growing in the past decades.

My first artifact was found in a shop in Guangzhou near the US embassy. The two-sided hand-stitched tapestry was not advertised for sale and hung high on a wall behind the register. The more intricate side features the traditional twelve Chinese zodiac signs and the reversed side features sixteen quilt-shaped squares with more geometric designs. Each side has bright and striking colors against the red backdrop. My mom admired the tapestry and managed to successfully bargain for it and the tapestry traveled from Guangzhou, China to Tallahassee, Florida soon after.

For my second selection, I decided to focus on my small collection of jade jewelry I have formed over the years. Two parts of my collection were gifts and one I bought myself. My mother gave me a black string necklace with a circular jade-green pendant and a red string bracelet with white-jade beads. Both items were directly from China and were given to me when I was a child. The third and final piece of my collection is my jade-green dangly earrings that feature Chinese happiness characters as the design. I bought these earrings myself during the Summer of 2015 when I traveled to China.

Artifacts hold much more meaning and value within them than their original sole purposes. My artifacts are connected to me personally and globally. As an adoptee from China, these tangible items have been personally important because they encourage me to learn, reflect, and cherish my cultural heritage. They connect to globalization because they participate in the five scapes of globalization: ethnoscape, finanscape, mediascape, technoscape, and ideoscape. These scapes can explain the nature of globalization through how many different exchanges between two countries can occur through that one object.

Michelle Calhoun: Hemp Dragon

A neighbor traveled to China many years ago and returned with this dragon. I treasure it. Here is the story of how they acquired it:

Blind, elderly man with only one arm, wearing nothing but rags and one sandal, and seated on a tiny stool in front of a small shack. A small boy, quite filthy, crouched in the dirt next to the man clutching a bag from which hemp was flying into the man’s hand. Using only his mouth, hand, elbow, thighs, and feet, the old man spun wondrous creations: dragons, turtles, birds, cats, snakes, and others. Many such sat, gathering dust from the street, on a cloth at his feet. Once completed, the old man would sit back, acrobatically light a cigarette using his elbow, hand, and toes, and smoke while the boy glued on eyes and painted a stiffening agent on the knot ends. When done, the boy would tug at the man’s rags and the process would begin anew. The gifter watched and tried to remember how he made them. However, the old man was a master of his craft and, though lacking a hand, operated with such speed and skill that it was impossible to discern his methods of creation. They observed this ritual for over an hour, as a small handful of tourists trickled by, one occasionally becoming smitten with one item or another. They would haggle with the boy over its cost as the man stared impassively. Offering double the asked-for price for the dragon brought a black and virtually toothless smile to the old man’s time-worn features and milky eyes. He winked and said that they could try to understand how, but without his magic, it was pointless.

Michelle Calhoun: Egyptian Decorative Plate of Luxor

I fell in love with archaeology after receiving a magazine about Egypt as a child. I could not pay for college, so I joined the Army to work on boats. I got orders to go to Kuwait, so I left Virginia and flew, first, to England, and then landing in both Italy and Germany, before finally landing in Kuwait. While there, our vessel traveled to Yemen, Qatar, Somalia, and Kenya. We stopped in Bahrain for fuel and alcohol, since Bahrain is the only Middle Eastern country that allows the sale and consumption of alcohol. At the base shops, there are trinkets one might like to send home to families and friends. In one shop, one could buy beautifully woven rugs from Iran, super-soft blankets with lovely designs from South Korea, decorative plates and objects from Egypt, and jewelry of many regions, motifs, and faiths from around the Middle East and North Africa. I left with three blankets, a rug with a mother and baby camel, and a decorative plate with a depiction of what life was like at Luxor during the pharaonic age. On the back, it still says ‘Made in Egypt.’

The journey for both myself and the item in question and our eventual meeting would have been unthinkable in ancient times unless one had had the freedom and funds with which to travel. That day, through globalization, a small Bahraini shop on a U.S. Navy base, on a tiny island in the Middle East, made money selling some kitschy Egyptian “junk” to a hillbilly from Appalachia, who was delivering supplies to Kenya, and that which was sold ultimately decorated a wall in Florida. The person who created that item likely never envisioned that it would end up here. When trying to locate said item for its picture, my children informed me that it was dropped, broken, and discarded last week. They had hoped I would not notice… I noticed.

Alana Gold: Mug and Glass Prism

In January, I received a mug as a birthday gift from either my mom or her friend who thinks I am still twelve years old. This eye-catching mug features a line of sitting cats that encircle the outside and a solid teal fills the inside. The cats are vibrantly colored and covered in stripes, spirals, and spots in a chaotically geometric style and lined with gold in some parts. They all share a similar posture and broad face, but contrast with different colors. They even repeat in pattern as if the cats themselves are a geometric pattern. This design was created by California-based artist Laurel Burch, who was well-known for making cats in this whimsical style. I despised anything this extravagant when I was younger, partially due to a repressive Christian education, but now I will brag about owning such a gorgeous mug!

Another object I analyzed was a glass prism with the outline of a traditional Chinese dragon inside. Surrounded by clouds of smoke, the winding dragon floats prepared to blast anything with the ball of energy near its mouth. I found it at a Goodwill while shopping with my mom about a year ago. It was probably donated by someone freeing themselves of excessive stuff. I remembered when these were popular over a decade, possibly fifteen years, ago, and it was fun to place them on top of colored lights and watch the light filter through the 3-D image within. It brings up a lot of nostalgia for me and may have been why I bought it. It now sits atop my bookshelf in my dorm room. It is more of an ornamental piece and not as practical as a mug. During the discussion of artifacts from class, I was informed by someone more knowledgeable about China that the dragon is usually seen on tourism signs, further indicating how iconic the dragon is to the outside world. One of these days I will get a color changing light to truly utilize this prismatic dragon.

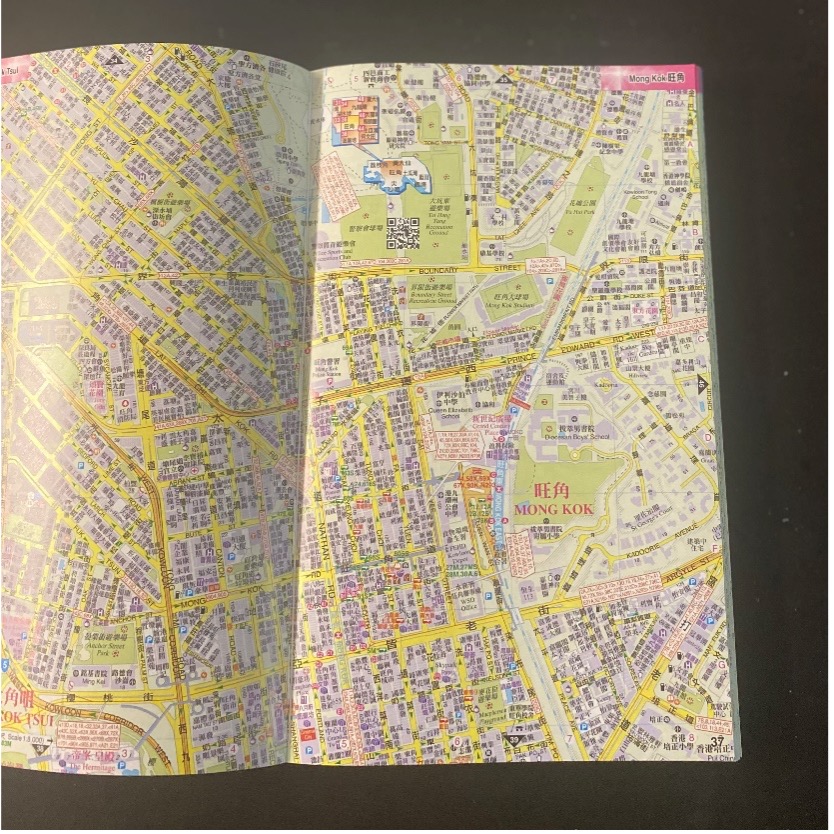

Adrienne Hill: Map

My best friend was born in Hong Kong and immigrated to the United States as a teenager. We became friends at NCF and he always talked about and shared his culture. We watched a lot of Hong Kong films, specifically films by Wong Kar Wai. The portrayal of the city seemed so vibrant and interesting, which sparked my interest in traveling there one. Two summers ago, he went back to visit. As a souvenir he bought me a map of the city that detailed the bus routes and all the major sites. Holding the map in my hands made me more excited to go there for myself. Since I can’t go physically right now, the map has lost its material purpose, instead now serving as a symbol of our friendship. Even though the map is an inherently useful object, as it contains information to get around the city, I don’t think I will ever use it as such. The map is still valuable to me because it was a gift and it has come to symbolize my future plans.

Not only does this map represent personal feeling and attachments, it also represents the movement of objects and people in our globalized world. There are different forms of movement such as migration, as my friend immigrated a different country, and travel for leisure. This movement of people that characterizes globalization also facilitates the flow of language. With travel being such an important activity today, signs in different countries have multiple languages written on them, showcasing how the movement of peoples affects the landscape of a stationary place. The movement of people across borders has accelerated due to new technologies like high-speed rail and airplanes. Through the flow of people and goods across political borders, I was able to procure an object that, without the process of globalization, I would never have been able to have or need.

Laylah Cortijo: Serigraph

My artifact for the class was a serigraph titled Melody in White by Huang Guanyu, which features a woman surrounded by flowers, playing what looks to be a traditional Chinese instrument. The creator born around the same time as my grandparents is well known for his emphasis on conveying modern and abstract Chinese aesthetics. Previously unaware, I learned how he took part in advocacy groups for preserving creative expression during the Cultural Revolution, and I saw that his portfolio seemed to bounce around stylistically. In his works lies elements of nature and a reflection of his culture through an innovative gaze. Lightly touching on anthropologist Arjun Appadurai’s words, I see Huang Guanyu’s work as his momentary mirroring of self, conserving vulnerability of a thing (the thing being his art) in a world that increasingly seeks change.

The more personal side of this artifact lies in my family’s history. My great grandfather was born in Wuhan, China during the 1920s, and my great great grandmother was born in Taiwan. Though without direct Chinese lineage, my grandfather grew up there until he left with his family at age 17 to flee bombing in Wuhan. I rarely heard about his childhood, but I always noticed the surrounding art and furnishings at family gatherings largely reflected his past. That cultural influence made its way into my grandparents’ home where I’ve grown up, my grandma buying the piece in the 1990s. This artifact has been up in my house for as long as I can remember, pictured in the back of every holiday photo.

I see Huang Guanyu’s Melody in White as a vague illustration of my family’s firsthand experiences with an increasingly globalized world. Unbeknownst to them, my ancestors’ past flows across continents have found a place of influence in the artistic choices of my present-day family.

Ginelle Swan: Qipao and Dallah

This artifact is called a “旗袍” or “qipao”. This qipao was gifted to me by an older woman in the Asian supermarket in Sarasota 2018. It is of a blue silk fabric and has silver embroidery down the entire dress. The qipao, also sometimes called a cheongsam, originated in the Qing Dynasty and was worn mostly by the Manchus. The Manchus created the Eight Banner system, where the Eight Banners functioned as militaries and was considered an elite force in the Qing military. The attire that the Manchus wore was a previous version of this dress that was slightly different in design and called a “changpao”. The changpao was originally worn only by Banner people to separate them from normal civilians. However, the changpao was enforced and eventually became the standard. This dress was then modernized by Chinese socialites in the 1920s and became known as the “mandarin gown”.

My second artifact is an Arabic coffee pot called a “dallah” or “:دلة”. My mother bought this dallah when she traveled to Egypt. It has a matte black body with a gold bulbous top that has gold arabic writing and designs. The sinuous handle of this dallah is also gold. This dallah set comes two small mugs that match the design of the dallah and a gold serving plate. A dallah is a traditional Arabic coffee pot. The dallah dates back to the 17th century. It is often correlated with social interactions, so it is common for a dallah set to be given as a gift during differing ceremonies, like weddings. It is a piece of my mom’s memory that she is allowing us to experience. In that same way, the merchants that my mother bought the dallah from, were sharing a piece of their culture.