It may feel like the past, yet, there is still so much hate in the present. Venice Theater presents God’s Country (1988) written by Steven Dietz which follows the story of the white supremacist group from the 1980s, The Order, that commit crimes to fund their organization and eventually assassinate liberal-leaning Jewish radio show host. The show runs through Sept. 9 through 25 and is a part of the theater’s Stage 2 series, featuring various other dramatic and comedic politically-driven productions through May 2023.

Due to the inherently controversial nature of the topics explored within the play, the presentation has stirred the pot among locals. During an interview with the Catalyst, Director Ric Goodwin addresses these concerns.

“I would like to emphasize that it is not political,” Goodwin begins to explain. “Our job as storytellers is to entertain, yes, but also to examine lives.”

When asked about the production, Goodwin describes how he met with Dietz, who gave him express permission to bring the play up to date. He also details some of the struggles he faced when presenting his own interpretation of the script.

“All the words I use are his,” Goodwin said, describing how hateful events as recent as August of 2022—like the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde Texas—are utilized to show the audience that occurrences such as these are no stranger in our world. “It’s happening right now, that is why we are doing God’s Country…these events were recent history, but not the past. It’s important, the story, the words, not who is saying it.”

He goes on to talk about the recent resurgence of white supremacy groups, even pointing to our own backyard. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in 2021 Florida alone harbored 53 established hate groups. Just this past summer, 31 members of a white supremacy group were arrested near an Idaho pride event, eerily reflecting the events within the play and harkening back to the worry of history repeating itself. This, paired with countless recent events of violence against many different groups, is what Goodwin states are one of the driving factors in the decision to put on the production, even with its inherent controversial themes.

“It’s about the human ethics, human politics, humanity” Creative Director Benny Ambush said. “These are frightening times and some choose to not look at it.”

“We are putting it out there for the audience…we are a ‘both end’ theater,” Ambush continued, referencing how the theater aims to portray these matters objectively. “Put that in front of the community and let them sample some or all of it,” Ambush continued.

Initially when Goodwin looked at the play, he said he struggled with where he would take the production. For example, the original script calls for a male-dominant cast, and while he could have taken the common modernizing approach of gender-blind casting, Goodman decided against this and stuck with the original production’s blueprint. .

“I thought about using a non-traditional cast, but it doesn’t work,” Goodman said.

“It made no sense to me” Ambush chimed in. “It’s a guy thing,” he added, pointing to the male-centric nature of the ideology presented in the play, which Goodwin agreed with.

Goodwin and Ambush stressed the objective viewpoint they aim to provide, and how they want to allow the audience to observe and take what they will from the performance.

“I don’t want to be fiddling while the world is burning,” Ambush puts it. “We don’t treat each other well, to be frank…the woods are burning.”

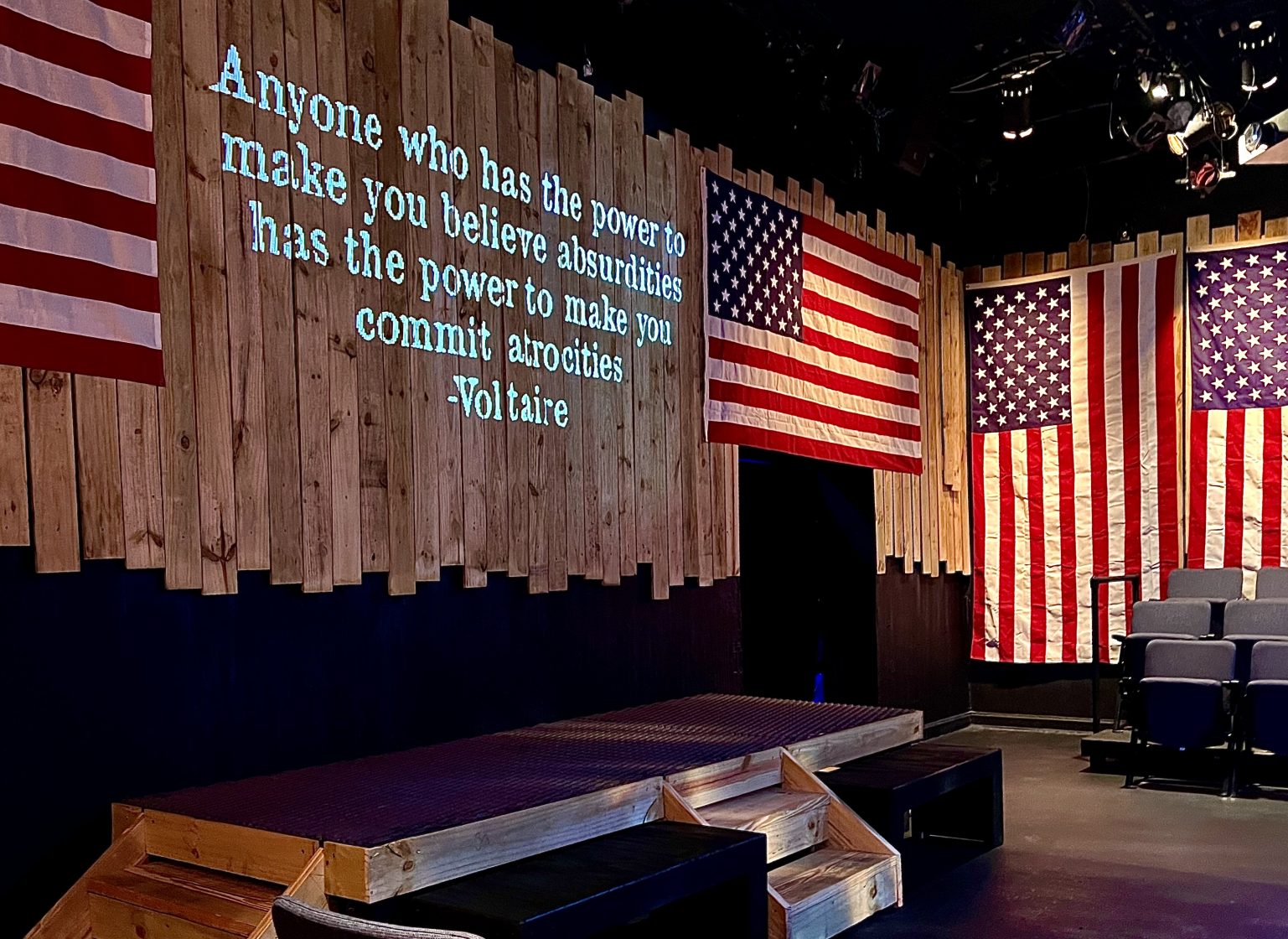

Many stories are written criticizing political environments and human nature as a whole. In Goodwin’s production of God’s Country the show opens with a quote from Voltaire, projected over the stage: “Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit atrocities.”

In contrast to a standard theater setup, God’s Country takes place in the Venice Theater’s non-traditional setup on their second stage. The theater is arranged in a thrust stage that extends out into the audience and allows them to surround the stage on three sides instead of just one. This setup allows the audience to become more engaged and seemingly take part in the story. Throughout the performance, actors regularly interact with the audience as though they were characters in the show rather than silent observers. This places viewers into the shoes of the jury overseeing the trial for members of the group onstage, and even puts them in the shoes of attendees at a meeting held by a white supremacist group.

Perhaps the most important—and arguably most intense—scene within the play happens at the end of the first act, just before intermission. In this scene, three high ranking members of The Order come out in Klu Klux Klan robes colored red, white and blue calling back to the patriotic colors of the American flag. The passionate preaching of the members is amplified by the use of red lighting, which appears at various points throughout the production to invoke anxious, intense feelings from viewers, creating a dramatic atmospheric shift. Yelling and affirmations continue until the peak of the monologue where the lights cut and the audience is left to intermission, and to their own thoughts.

“Let’s see how many we lose,” Goodwin said to the Catalyst reporter sitting next to him in the audience as the remaining guests funneled out to the lobby. But, in a surprise to both parties, seats were still filled after intermission and it seemed that nobody had backed out.

Although the production focuses on the gritty and horrendous acts taken by many of these members during the 80s, it also provides an interesting justification of why they acted the way they did. For example, the play demonstrates that many members join for stability and to help provide a better life for their family. This is by far one of the most interesting takes within the storyline, as it examines the gray morality of these characters, and how ignorance to the impact of your actions can cause damage that was not initially intended.

Goodwin also utilized masks to add a dreamlike, almost reminiscent air to the performance. During intermission, he described his inspiration linking back to the Greek tragedy masks and the emotions they convey. Utilizing the blank canvases of flat and emotionless masks on the background actors, attention was instead pushed to the interpretations of the protagonists. Whether they were helping or harming, acting as like-minded benefactors or brutal white supremacists varied based on what different characters would describe—and with no faces to identify on these figures, the audience was instead left to come to their own conclusions.

Towards the end of the production, the audience is shown a scene of a father, who follows white supremacist ideals, discussing his son and the consequences of bestowing his beliefs onto him. He describes years of “warning” his son about Jewish and non-white people, and after years of instilling these beliefs into his family, he goes into his son’s basement one day only to find an upsetting scene. Among the guns, weapons and other malicious materials were two photos. This brings him to a realization, and a haunting delivery by the actor:

“A picture of a father proudly displayed next to a photo of Hitler, in a basement where I’d never been.”

The weight of the statement alone pushes the driving ideals of the performance. History is in the past, but that does not mean it is okay to forget it. For if history is forgotten, it is bound to repeat itself. Within the director’s note, Goodwin presents a quote from renowned author Mark Twain which captures the essence of this idea:

“It is not worthwhile to try and keep history from repeating itself, for man’s character will always make the preventing of the repetition impossible.”

Goodwin’s goal with this production was to provide the public with a reminder of history and the important place it holds. Ambush also provided a quote from Shakespeare during his interview:“To hold as ’twere the mirror up to nature” Goodwin elaborates on this point, stating, “Hold up a mirror to society so we look at ourselves.”

Goodwin and Ambush expressed that their goals within the production were to simply create that mirror for the public, whether or not they look into it is their choice, but it doesn’t go away.