With only about 50 years and 5,000 alums under our belt, I’m frequently taken aback by the immense, enthralling and unique history our tiny college possesses. While browsing through New College’s digital and physical archives, moments arise when I imagine our campus as a series of snapshots on a timeline, snapshots filled with interesting backstories, rich history and discussion starters that easily connect to current dialogue occurring among our students today. I had this experience recently when NCSA archivist and thesis student Joy Feagan handed me a newspaper article from 1971 titled “‘Feminist’ sit-in turned into sleep-in.” The article chronicled exactly what the title describes: a protest organized by women on campus in the then President’s office that continued overnight because participating students felt their demands were not met.

Let’s step back and look at the logistics of campus gender relations in the the 1970s. According to College Board, in 1970, 55 percent of male high school graduates and 49 percent of female high school graduates were enrolled in college. Through to 1975, men continued to be more likely enrolled in college close after their high school graduation. This gender gap was reflected at New College. A massive college evaluation document from 1970 emphasized the gap present on campus, noting that not only did the student body contain significantly more men — but so did the faculty population as well. This information is stated in contrast to today’s numbers, which nationally display women consistently enrolled in higher percentages than men since 1995. US News most recently reported that the gap has completely switched at New College, reflecting this national average, with women as the predominant gender on campus by more than 15 percent.

The feminist sit-in of 1971 is one of many reactions to the stark and obvious gender gap present on New College’s campus in its early years. Referencing the article that Feagan handed me and another article from the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, the sit-in seemed to occur over the following concerns: the lack of women faculty in proportion to the number of women on campus, the want for a Women Studies program led by the Women Committee, inadequate security and self-defense classes, nonexistent abortion services, inadequate contraceptives, fuzzy patient-doctor confidentiality, the need for a cooperative child care center, and proper pay for women who worked as maids, maintenance personnel, secretaries, etc.

Reaction to the feminist sit-in was not all positive. In fact, there was a decent amount of documented backlash from students and administration alike. For example, campus physician Dr. Morton Mark resigned.

“The sit-in apparently attracted little attention on campus,” the Herald-Tribune article said. “Said a women not involved in the movement: ‘It’s like being the 37th man on Mount Everest. Nobody knows you’re there or cares.’”

That aforementioned piece by the Herald-Tribune was titled “Elmendorf labels demands unfeasible.” John Elmendorf was the second president of New College, and responded to the protest in his Office with a poignant letter. The letter, dated October 29, 1971, begins by acknowledging the gender gap and the imperfection that existed between genders on campus. However, as soon as the second paragraph hit, the letter took an abrupt change in tone. “In the present instance, a small and clearly non-representative group of women students has bypassed the method of reasoned discourse in favor of a now ‘fashionable’ technique which includes the presentations of obviously unfeasible ‘demands,’ followed by the ‘occupation’ of an apparently strategic area of the campus,” Elmendorf explained. He went on to state that in the women’s defense, they were just first-years led by an advisor who was a “newcomer” to campus and “quite evidently unfamiliar with the processes of the College which have already made measurable progress in implementing most of the ‘demands’ they presented.” Elmendorf’s letter condemned the feminists’ actions because, according to him, they backtracked on progress. Elmendorf blatantly calls the protest “a mindless act” and “ an immature, planned and manipulated act.”

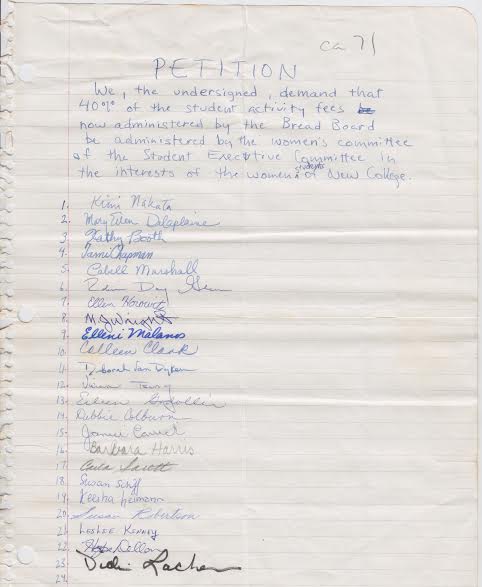

Many bodies on campus expressed support for the experience of women as an underrepresented community on New College’s campus in the 1970s. As early as 1969, demands were being made to even the gender ratio in enrollment. On March 12, 1969, the Student Executive Committee wrote Dean of Admissions Robert J. Norwine asking the department “to take all steps to commensurate with quality which will will help restore the balance between men and women at New College, and to admit at least as many female as male students in next year’s class if at all possible.” A petition scribbled on notebook paper from 1971 asks “that 40% of the student activity feed now administered by the Bread Board be administered by the women’s committee of the Student Executive Committee in the interest of the women students of New College.” Only 23 students signed the petition.

The evaluation of the College from 1970 cited earlier states that oftentimes women felt objectified on campus and viewed as a “scarce resource.” The document goes as far as to suggest the creation of a Dean of Women position in response to “the fact that the New College faculty and administration are almost exclusively male.”

“There is an obvious disparity in the ratio of women students to women faculty, as compared to the ratio of men students to men faculty,” the evaluation said. “However, rather than establish a position and then bring a woman to fill it, the Committee believes that extraordinary effort should be made in every division to recruit women faculty members, so that the kinds of relationships that now occur between students (who are male and female) and faculty (predominately male) can occur on a more equitable basis as far as the sexes are concerned.”

Further apparent in the archival pieces are differences in thought toward feminist methodology within the College at the time. A publication titled Alternate Weekly, in its April 26, 1971 issue, published two letters disagreeing with a previous work in an issue of the Cauldron. “Dear Cauldron,” the letter states. “How are you going to alter men’s minds with the garbage that was floating through your last issue of April 21?”

One point that seemed to be consistent, however, was the male-dominated atmosphere that hailed on campus in the 1970s. In a 2004 issue of the Tangent, staff writer David Higgins wrote an article on the history of Walls. His research contacting alums concerning the campus tradition has been filed away in the archives. Many of the emails from 1970s alumni mention the gender disparity that was most certainly present during their time at New.

“Palm Court Parties, yes male-dominated and controlled…,” alum Ellen Goldin (‘74) said at the beginning of her message.

“Upperclassmen (and I do mean men) put together Palm Court Parties. They collected money for the beer, pulled together the sound, started through the tapes,” alum Ginger Lyon (‘70) said. “(Unlike now, males slightly outnumbered females, and the male archetype was strong.),” she added in the email.

It would be nearly impossible to even touch on gender relations at New College today in one concise article, especially taking into account explanations of gender fluidity and the destruction of the gender binary. However, relating strictly to feminism, there are some visible initiatives currently occurring on campus to mention. The first is Feminist Fridays, which occurs each Friday at lunchtime in ACE Lounge. Faculty, students and staff are all invited to discuss a different topic each week relating to feminism. Another movement is the Feminist Writing Collective, which published its second Zine at the end of ISP. Inside that Zine, the Collective describes itself as “a collaborative tutorial that examines feminist thought, critiques, and artistic production.”