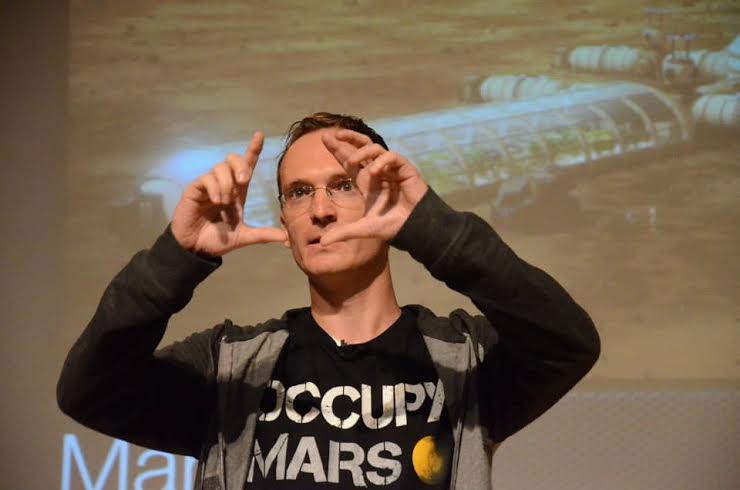

If Lennart Lopin is chosen as one of the final 24 to be sent on a one-way trip to Mars, he may perish in 68 days, or he may spend the rest of his life watching a blue sunset from the surface of the Red Planet, 55 million kilometers from all other known life. Lopin, a Sarasota resident, has advanced to the third round of the selection process for Mars One, the first attempt to establish a permanent human settlement on Mars. Lopin is one of the final 100 candidates for this legendary one-way ticket, weeded from the original 200,000 worldwide responders.

Lopin is a 32-year-old software engineer from Austria and a father of four. Mars One, a not-for-profit project being developed in the Netherlands, plans to send six crews of four, departing every two years, starting in 2024. The first unmanned mission, a seven-month journey, it set to launch in 2018. Mars One intends on sending a demonstration mission, communication satellites, two rovers and several cargo missions to build a reliable living unit in the coming years and only with existing technology.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have recently criticized the mission. They write, “The level of oxygen in the atmosphere would become a fire hazard as the colony’s first wheat crop reached maturity, and venting the oxygen would not solve the issue.” They predict the first crew fatality would ensue after a mere 68 days. Despite this, Mars One has garnered the support of Dutch 1999 Nobel laureate in physics Gerardus ‘t Hooft, as well as recent financial backing from a number of sponsors. The cost is currently projected at about $6 billion.

“They were looking for 1 million people but they only got 200,000,” Lopin said. After the initial signup, detailed application forms were sent out asking about background, skills, incentive and history of previous high stress and even life threatening situations. Each applicant was allotted exactly one minute for a video presentation. “After that, there were only 1,050 people left,” Lopin said. Next came a call for extensive medical examinations to be sent in, which reduced the number of potentials to 770.

The next step was originally a call for film interviews, set to be conducted by a television production company, as it was believed that Mars One required extensive media coverage in order to be funded. When Mars One started to receive financial backing it made a new plan to produce a documentary film instead of its original idea: a reality television show.

“Mars One is not as dependent on the media part which was always the most critical part of the plan because of financing; now the media is just going to be an extra benefit,” Lopin explained. “Obviously as humans, there is something in us that finds this very fascinating, so we can use that to actually get some money out of it down the road.” Lopin mentioned perhaps having Coca-Cola and Pepsi compete to have a sign on the Mars outpost, “Or Apple and Microsoft, Apple has billions just lying around doing nothing!”

The interviewing step entailed four weeks of intensive study to prepare for all possible questions. Candidates were expected to answer questions about past missions, various countries’ success rates on missions, details about the Mars One mission, details about Mars itself and so on. Materials sent out to candidates included a printout the length of a novel, which provided information for the three technical and three psychological questions. There were also impromptu questions asked, some of which were later revealed to be critical for the next progression. Lopin had his interview on January 5.

They asked him if he would return to Earth after three years given the option, and he responded with a resounding no. “I’m not going to return […] Why would I leave this all behind? I’d rather push in the other direction […] push to the next boundary. That would be the way to go.” In the middle of February, the 100 finalists’ names were released, and Lopin had advanced.

“It was pretty intense, but really other than that there were really no criteria,” Lopin said. “If you were a physically healthy person and four weeks of studying this material was enough for you, then you really had a good shot at getting through this interview.” Another hundred applicants disappeared leading up to the online interview.

“I’m pretty sure there’s going to be a constant flow of people who, in the middle the night realize ‘wait a second, this is getting real and I don’t really want to go to Mars,’” Lopin laughed. Lopin explained that Mars One is more likely to succeed than other missions, at least in its initial stages, because it is more financially realistic.

“The main problem with Mars is that you can get there, but coming back makes the price ticket incredibly more expensive,” Lopin explained. “Because the problem is you have to take all the propellant over there, and that makes it very expensive.” Lopin detailed a plan configured in the 90s to ship the machinery first and then create rocket fuel on Mars itself for refueling. “NASA said they could do it for $10 [billion] or $20 billion, but once it looked serious everyone wanted to be a part of it and suddenly it was $500 billion.” Congress then rejected the proposal. “NASA was not talking about it so we always thought it was impossible […] Always saying in 30 years, in 30 years, which meant never, really.”

Lopin mentioned his unlikely hope finally manifesting in “The Case for Mars,” by American aerospace engineer and author Robert Zubrin, which contains a detailed plan for the first human landing on the Red Planet. It focuses on lowering the cost through automated systems and manufacturing a return based on available Martian material; it also considers the possibility of terraforming. “If you read ‘The Case for Mars’ and then [read] about Mars One, the plan is very similar but it’s even cheaper than Dr. Zubrin’s because they cut out the return ticket. They say let’s just go there and try to survive and try to build all the necessary foundational things for mankind to live […] That’s why when I saw it I didn’t think it too crazy, because of this book; otherwise I probably would’ve thought that this was insane and never going to work.”

Lopin described his fascination for astronomy and science as a young child, stating he eventually became so captivated he wished to be abducted if only to explore further. “What I really wanted was to get away from this planet. I thought that everyone had already discovered everything already and thought ‘there’s nothing left for me.’ On the one hand you’ve got Star Trek and Star Wars and you read astronomy books so you know that those worlds are out there, and then you look at the only major spacefaring nation – the United States – and they had one space shuttle explode and basically stopped everything. It was really devastating, so I was thinking maybe there was another way into space.”

Lopin then became enthralled, as was his tendency with most subjects, with the possibility of abduction. “I thought maybe I could communicate with them and they’d come and take me but instead of other abductions I would ask them to keep me.” With the guidance of science fiction, Lopin began experimenting as an 11-year-old with ideas surrounding telepathy, all in the hopes of fulfilling the grand plan: escape from Earth.

“The whole motivation was so that I would somehow train my mind so I could communicate with aliens and get them to come,” Lopin explained. “Never really worked out, but it got me more and more drawn into Eastern philosophy.”

“The idea of training your mind and the possibilities of deepening your concentration, your insights, into how the mind operates and works; I got very fascinated.” This led Lopin to Buddhism as a teenager. Lopin’s parents, concerned with what they saw as an obsession, sought out a Buddhist monk in hopes of advice. They were told to gift their son a two-month trip to Sri Lanka, promising that he would swiftly return once he witnessed poverty. Lopin, disinterested in the modern manifestations of the religion, agreed for the sake of maximizing his allowance, traveling 5,000 miles in the hopes of finding cheap books.

To everyone’s surprise, after two months, Lopin wrote to his parents informing them of his decision to stay. After much distress on the part of his parents, Lopin finally struck a deal, promising to return and finish school in exchange for the required permission to become a monk afterwards. They believed he would change his ideology. They were wrong.

“I had a new goal, a new mission. I tried to learn the language, lived like a monk as a teenager in my room, went to the forest after school to meditate. I was totally dedicated and as soon as the high school exams were over, I took the ticket and was gone.” Lopin stayed for three years, before tiring of the organized aspect of the religion. He grew weary of the views and practices he saw as divergent from the original teachings, and left for Germany. “I went because of Buddhism and I left because of Buddhism.”

Lopin earned a degree in computer science and linguistics, worked for a while in Hamburg at a software company, and then left his job in hopes of finding more individual and social freedom, as well as a common dedication to scientific inquiry that he believed Germany lacked.

“People ask ‘why this obsession with Mars?’ and it’s not really that Mars is such a great thing, there are probably greater things out there, it’s just that we have to start somewhere.”

Lopin is enthralled with the foundation-building aspect of the mission, what he calls “bootstrapping civilization,” above all else, but also detailed his excitement for the exploration of Mars’ terrain as well as the search for microbial life. “Underground cave systems, the highest mountain in the solar system, the deepest canyon in the solar system, all on Mars! So it’s probably not gonna get boring,” Lopin laughed.

The remainder of the selection process entails physical and group challenges. After another intense three days of observation only 25 men and 25 women will remain. Then the group will be tested on ability to cope in isolation, among other things. In the end, the final 24 will be officially hired and will be trained over the next nine years in everything they will need for the mission, which will be for the most part repair, maintenance, research and construction. They will likely cycle the 24 through isolated, “Mars-like” outposts, which could mean being relocated to a desert or arctic environment, or an alteration of both.

In light of the possibility of leaving anything and everything behind, Lopin’s motivation and reasoning are often questioned. It has been said on the topic of the Mars One candidates that one has to be insane or fundamentally flawed in some way to choose this life, but Lopin, a pioneer born in an age of relative stillness, sees only an opportunity for the advancement of mankind.

“People ask ‘how can you leave your kids behind?’ and for me, I imagine all the sacrifices people made in the past just so that we can sit here right now just talking,” Lopin said. “For me this is something that is very close to my life, I can almost feel these people in the past […] this is something I feel like is almost a debt and not in a negative sense, but a positive sense. If my life just pushes this boundary a little bit then I have done my duty, if you will. I would have done the best thing that I could’ve ever done for my kids and for their children’s children.”

Lopin concluded, “Even if this falls through, if it never becomes anything, a big part of this is just inspiring the next generation. It’s about looking forward.”

Information for this article taken from:

SPACE NEWS

- NASA discovers massive ocean on Jupiter’s moon, Ganymede

- Astronomers discover black hole with a mass of 12 billion suns

- China working on new Long March rockets; likely to fly later this year

- Arianespace signs first U.S. customer, planning to launch several Skybox Satellites in 2016

- Mars rover Curiosity regains use of arm, returns to research

- NASA’s spacecraft Dawn completes its 7.5 year journey to dwarf planet Ceres; finds evidence of possible ice layer

- Evidence of hydrothermal activity found on Saturn’s moon Enceladus

- NASA test-fires largest motor measuring 177-feet, a step towards deep-space exploration