The Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith: Flowers, Poetry, and Light exhibition at Marie Selby Botanical Gardens moved me profoundly. It’s incredibly creative, contextualizes in ingenious ways the revolutionary output of two artists in terms of their relationship and lives, all in the setting of a beautiful botanical garden, ultimately asserting the inseparable relationship between life and art.

The exhibition is being showcased at the Selby Botanical Gardens Downtown Sarasota campus, 15 acres dotted meticulously with a vast variety of plants, particularly “epiphytic orchids, bromeliads, gesneriads and ferns, and other tropical plants.” Marie Selby Gardens’ downtown campus has hosted the annual Jean & Alfred Goldstein Exhibition Series since 2017, “which explores the work of major artists through the lens of their connection to nature.” Last year’s exhibition was Roy Lichtenstein: Monet’s Garden Goes Pop! and the year before, it was Salvador Dalí: Gardens of the Mind.

This year, the exhibition focuses on the creative output of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and musician/poet Patti Smith through the lens of their connection to nature. The exhibition also focuses extensively on the relationship of the two artists, which makes the exhibition as much about art as about life.

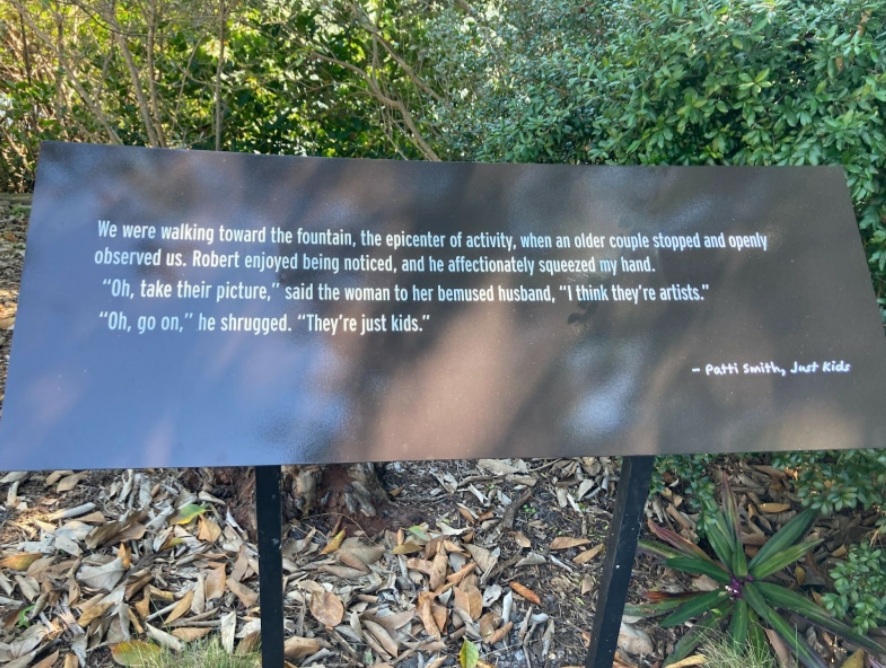

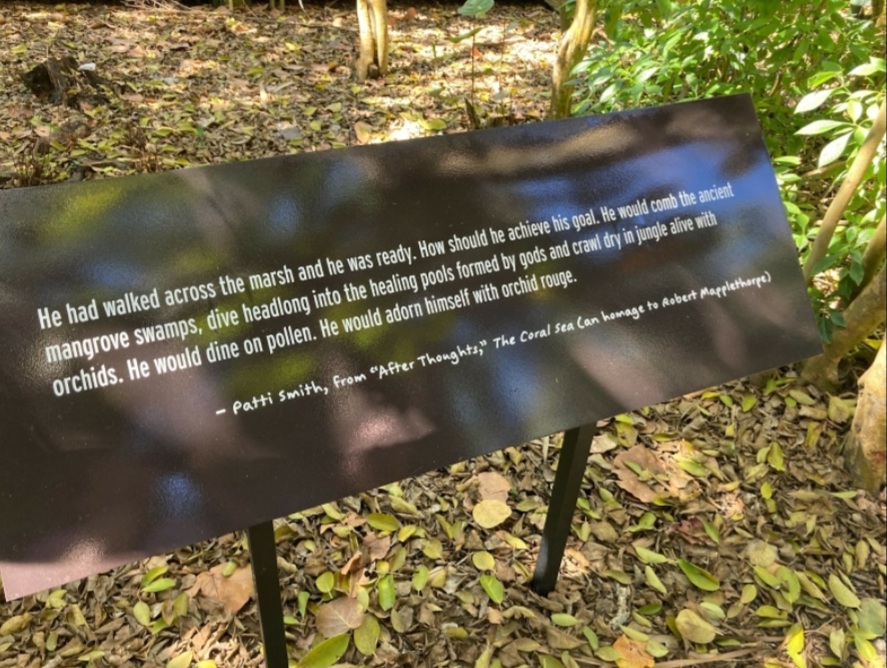

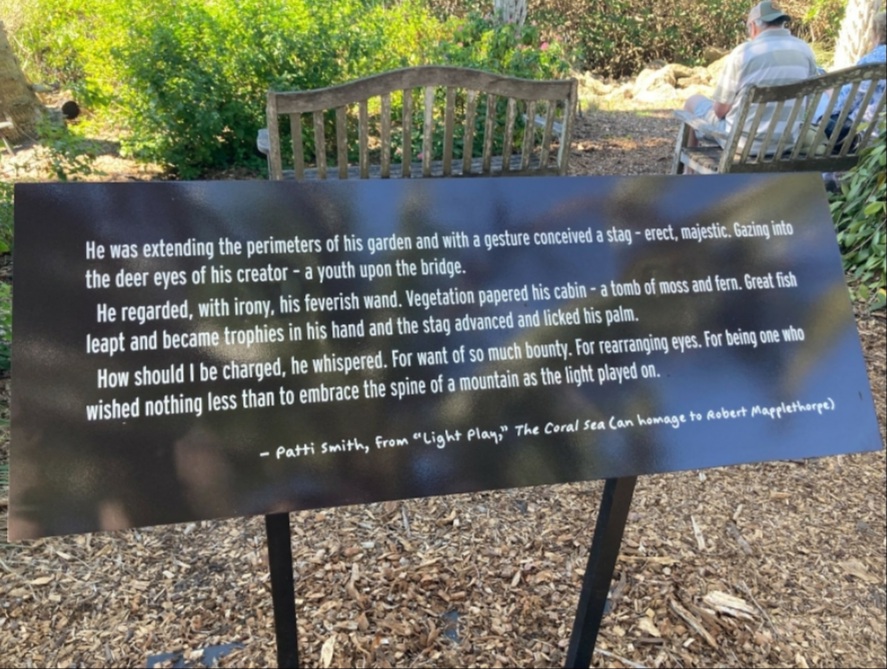

Of the duo, Smith is likely the better-known—famous for her critically acclaimed proto-punk musical output in the 1970s, which helped earn her the title “Godmother of Punk.” More than a punk musician, though, Smith is a poet. It is her poetry, not her music, which follows you on the path through the garden. Seen on reflective metal signs, standing noble like cairns, commemorating events between Smith and Mapplethorpe as though they happened directly in the space in front of you.

The first inscription, found early on in the path, contextualizes the exhibition: the story of Smith and Mapplethorpe, as a song in the key of their youth. The story of Smith and Mapplethorpe begins, and largely ends, before either of them became famous or had carved out their positions in the art world, in their early-to-mid-20s. Now, both of their artistic credibility is indomitable, but it wasn’t always so.

Also early on in the exhibition is the first representation of Mapplethorpe’s photography. Mapplethorpe is best known, both now and in his lifetime, for his nude studio photographs, particularly his gay BDSM portraits. However, while less controversial and legend-cementing, Mapplethorpe produced a cornucopia of still lives of plants, at least much of which can be seen as a continuation of his photographic exploration of the sexual.

According to Smithsonianmag, “He liked to play with eroticization of the flower, its associations with lushness and vitality, but also with the transience of life.”

The first representation, however, is more subdued.

It exists as a thin wall of white plasterboard with a square hole, a frame. Behind the white plasterboard is a black plasterboard, and in between is a plant. These three layers create the impression, from a few steps back, of the two-dimensional, of the photograph.

At a point in the garden, there is a bit of shade—a sort of grove—close to the shore with the bay, and here there are benches and a speaker playing Smith reading aloud the story of her and Mapplethorpe’s relationship.

“I promised Robert the day before he died that I would write our story,” Smith said to NPR in an interview. “And it took me 20 years, but I kept my promise.”

That memoir is Just Kids, released in 2010 and the source material for much of the exhibition.

Here, the entire story can be heard, or one can press along. That story, however, is one I believe that New College students, particularly those who fancy themselves artists, ought to listen to. It is a story of youth and what it means to be an artist, of how relationships build us, and of the transience of life. As one walks through the garden, the knowledge that Mapplethorpe died in 1989 due to complications from HIV/AIDS at the age of 42 asserts that transience.

About halfway through the garden exhibit, a much larger, more complex version of the first representation of Mapplethorpe’s work appears. The first is encountered before learning the story of Smith and him, this one, afterward. It is a three-pronged pure white hallway that forcefully highlights the colors and character of the plants on display.

When I came to this exhibition, I was curious as to how Mapplethorpe’s work would be showcased. The approach of making the photograph three-dimensional, real—not pictures on a wall but rooms in real space, was pleasantly surprising.

The essence of photography is the frame. What is in the frame, what is out of the frame—and, for what is in, where within, how much within, and in relation to what else—these are the questions whose answers define a photograph. The curators of this exhibit demonstrated this better than I could have imagined. One of the powers of the frame is its responsibility to distribute and assign context. By removing a plant from the context of the garden, the individual from the public, it’s almost made a person, given personhood—and then the compositions expose this personality and accentuate it.

The power of the frame is not unique to photography, but it is especially clear in photography. However, the fundamental concept of what is included and what is not, the manifestation of thought and mind, is arguably essential to the very essence of what it means for something to be art. It must be intentional, the expression of a mind, the manifestation of meditation.

The juxtaposition of the garden, where plants bleed together with the unabashedly meditated 3D frames of Mapplethorpe’s vision, containing always a single plant, compels the viewer to see the plants as individuals. Never have I felt so connected with a plant as I was when I shook one’s hand through the constructed frames at Selby.

The juxtaposition accentuates the individual against the collective, and, reciprocally, the collapse of distance between the real and a photograph into merely the real makes the conversation between the viewer and plant more intimate. It left me speechless as I stared and reconfigured what made something a photograph. These aren’t sculptures, they’re not dioramas. The frame—the inability to walk around the subject, only in front of—bars these labels. But, unlike a photograph, I could touch these plants, I could get closer and farther. Yet Mapplethorpe’s mastery of form and composition remained evident. According to artnet.com, “[Mapplethorpe] was concerned with Classical aspects of beauty, whether in his nudes, floral still lifes or self-portraits—light, shadow, composition and form were central to all his work. ‘I don’t think that there’s that much difference between a photograph of a fist up someone’s ass and a photograph of carnations in a bowl,’ the artist said.”

In his commitment to beauty, at times I felt as though I was seeing these flowers in an almost sexual way, licentiously exposed to me, posed so that their beauty was most captivating, like a nude.

At the end of the path, there is a record player surrounded by flowers. The record is playing Smith’s fourth studio album Wave. The album was released in 1979 and was her last until 1988. She spent the time in between focused on raising a family with her new husband Fred Smith. The choice of Wave is a perfect one.

A little bit further, there is an indoor exhibition at The Museum of Botany & the Arts, where I was unable to take pictures as there were a great deal of copyrighted photographs of the two artists. However, it “presents Mapplethorpe’s exquisite flower photographs, including Orchid, Irises and Hyacinth, made at Graphicstudio at the University of South Florida (USF) in Tampa together with Smith’s haunting writings and lyrics. Reproductions of historic photographs of the two artists, their friends, lovers and living spaces tell the story, accompanied by Smith’s own words,” according to Selby’s website. And yet, they themselves sell short just how moving this part of the exhibition was. One poem that was shown was “Wild Leaves,” an excerpt of which is:

“Wild leaves are falling

Falling to the ground

Every leaf a moment

A light upon the crown

That we’ll all be wearing

In a time unbound

And wild leaves are falling

Falling to the ground”

The beauty and the brevity of life are front and center, told through natural themes. This is true of the poem above, and it is largely true of the exhibition as a whole. The garden, as the background to the story of the two artists, is always changing. It is beautiful and it is cyclical, transitive. From blooms to wilts, growth to decay, it lives, gives and dies. An analogy with the garden of Eden is near inescapable. If it is Eden, it’s a modern one; one that tries to grow through cracks in the suffocating cement of hardship and anguish, of an imperfect world.

Smith and Mapplethorpe dated for five years, through poverty and tumult, until Mapplethorpe left for Sam Wagstaff, an art curator who legitimized and supported Mapplethorpe’s creative output, and with whom he stayed until his death. Smith and Mapplethorpe remained close and platonically entwined, also until his death. Smith fell in love with her husband and raised a family with him until he died of a heart attack in 1994.

A quote of Smith’s sings in my mind: “In art and dream may you proceed with abandon. In life may you proceed with balance and stealth. For nothing is more precious than the life force and may the love of that force guide you as you go.”

While I spent more than three hours at Selby, I did not experience the entirety of the exhibition. I missed the Tropical Conservatory, “world-renowned for its collection of orchids and bromeliads,” which “is reimagined as a photography studio and gallery, complete with drop cloth, box lights and living plants framed and suspended as still lifes.” I plan on visiting again to experience this bit that I missed, as well as the parts that I didn’t. I will be able to do so until the exhibition closes June 26, 2022. This gives me, and you, plenty of time to visit and revisit this wonderful exhibition and story. Moreover, New College Students, so long as they bring their student ID, can enter for $10 rather than $25.