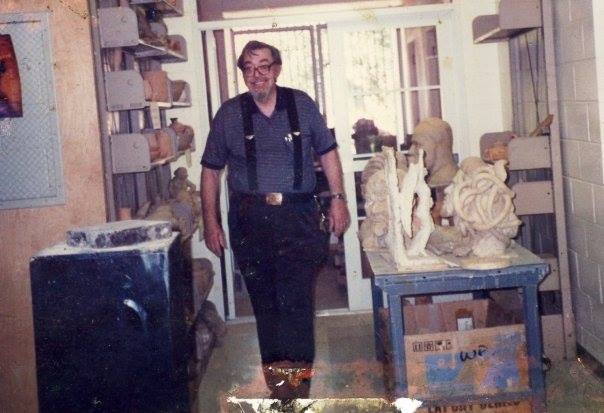

All photos courtesy of Dory Cartlidge McQueen.

Jack Cartlidge’s relationship with New College began in the 60s when he became an adjunct faculty member, running weekend sculpture tutorials out of his home in South Sarasota.

“He would take his pickup truck and go to New College and pick up 10 or a dozen students,” Cartlidge’s daughter Dory Cartlidge McQueen shared. “They would ride in the back of the pickup truck, and they would come to the house on a Saturday and work with him all day.”

These tutorials transformed into New College’s first sculpture program in 1968, when Cartlidge became Professor of Art—a position he would hold until he retired in 1998. While at New College, he created a number of massive bronze and ferrocement works now scattered across the Sarasota area. One of these statues, Band of Angels, is located outside of Palmer D across from Heiser (for more information about the statue’s recent renovation, see Catalyst article “Band of Angels restoration complete after complaints from alumni.”)

Many of Cartlidge’s experimental techniques were developed to reduce the cost of fabricating his monumental works—and the Art Department’s expenses.

“He was really good at figuring out how to do cool stuff—it was as much engineering as art—with practically no money,” Steve Jacobson (’71), Cartlidge’s long-time Teaching Assistant (TA), said. “He never had any money. The whole budget for the sculpture department was like $1,200 dollars a year.”

Instead of buying new metal for sculpture and welding, he collected rebar and other discarded metals from local junkyards. To make his pseudo stained-glass sculptures he would glue mosaic tiles he ordered in bulk from Mexico to large slabs of glass. According to Jacobson, Cartlidge would also have the students make their own ceramics clay from hundred-pound bags of brick dust he bought from a brick manufacturer in Plant City. They mixed the clay by hand on long wooden benches until the school saved enough money to buy an old clay mixer.

One of his most well-known pieces is Nobody’s Listening, located outside of Sarasota’s City Hall. It was the first work Cartlidge created using what would become his signature copper repoussé technique. Repoussé involves heating sheets of metal and hammering them from behind to create works that mimic the look and aging process of solid bronze—without the expensive casting process or material costs.

“These were big pieces,” Jacobson said. “To do them in bronze would cost tens of thousands of dollars and unbelievable amounts of work.”

Cartlidge used recycled roofing copper for the sculpture, burning off the old tar in his backyard.

“It took him three years to do that piece,” McQueen said. “I remember I could hear him at 2:00 in the morning out there—‘bang, bang, bang, bang.’ He’d work the piece and then he’d take it apart and put it back together.”

Featuring two groupings of chunky humanoid figures, the work was intended to express the difficulty of making the decision to reject the status quo and remain steadfast in one’s convictions.

“Nobody’s Listening is often misinterpreted,” McQueen explained. “It’s not about the schism that happens between the crowd and the individual figure. The individual figure is a leader, he’s walking away from the crowd. It’s hard to walk away from the crowd, it’s hard to be the one that’s standing alone.”

Cartlidge was steadfast in his own dedication to social equality, helping to start Sarasota’s first National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peoples (NAACP) chapter and working closely with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) for much of his life. He dedicated one of his sculptures, entitled Three Civil Right Workers, to Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman. All three men were civil rights activists who, in 1964, were murdered in Mississippi for their belief in social equality.

“That was a big turning point for him as far as his artistic activism,” McQueen said.

Cartlidge was also steadfast in his belief in New College.

“The biggest thing I take away from him and his legacy is how much he believed in the New College philosophy,” McQueen said. “He believed in experimentation. He believed in not being afraid to fail.”

Cartlidge dedicated 30 years to the school, leaving behind Band of Angels and the Art Department, as well as a lasting impression on many of the students he worked with.

“An awful number of students—even if they didn’t become artists themselves—were influenced by Jack Cartlidge,” Jacobson said. “He was as much of an influence on my life as anybody—except maybe my parents.”