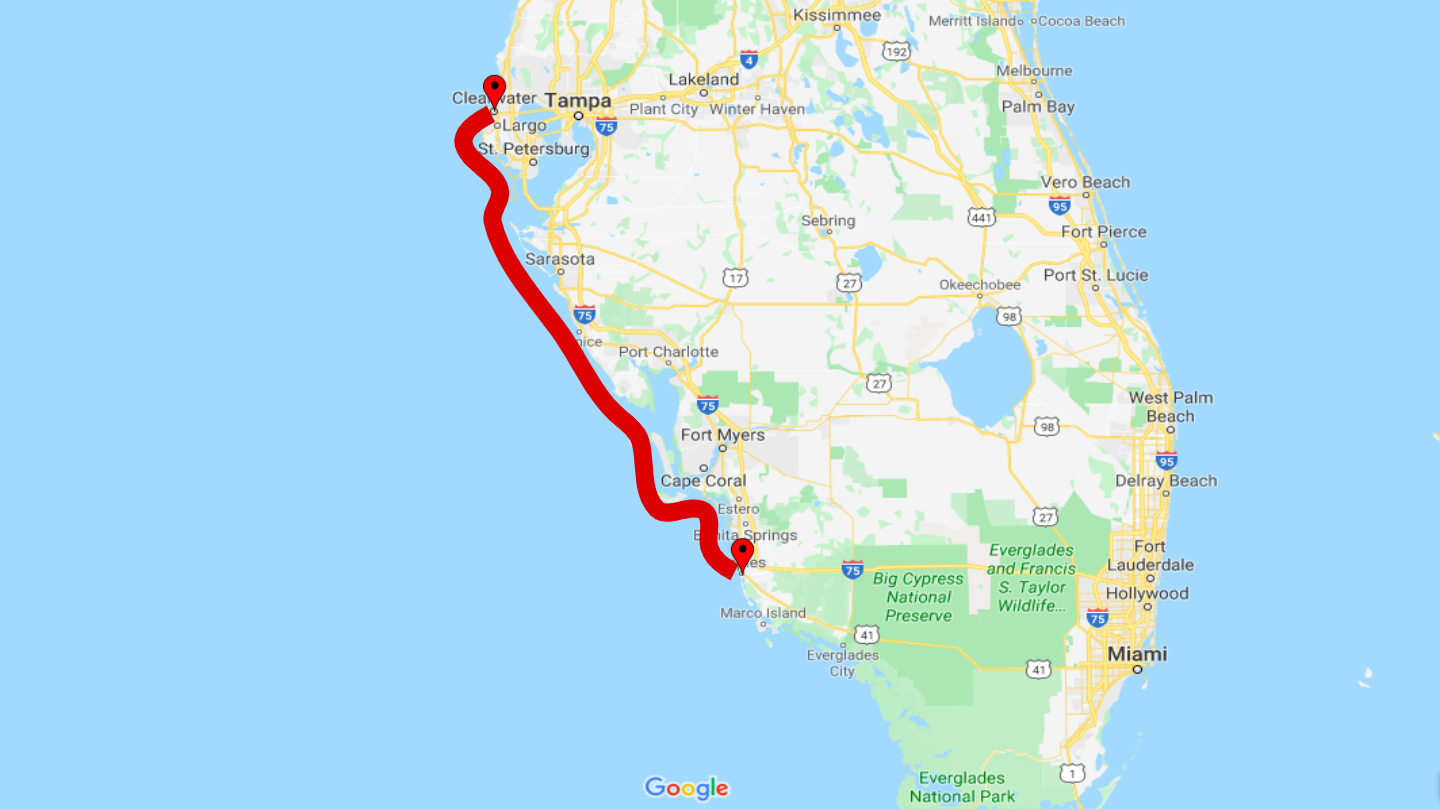

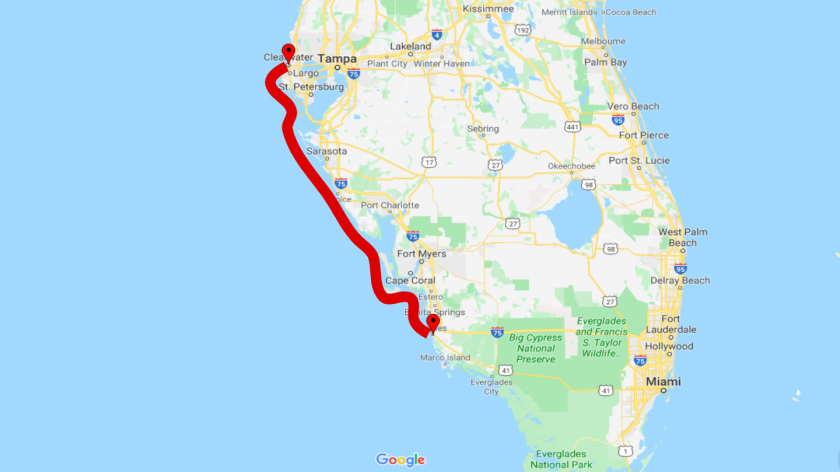

In 2018, red tide affected Florida’s coastline from Clearwater to Naples.

Florida continues to deal with the coastal infestation known as red tide. Local, state and national initiatives have been researching and working on ways to mitigate the issue. Richard Stumpf is an Oceanographer with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and shared the technicalities of the development process of red tide, as well as his opinions on mitigation practices and the impact of red tide on the marine and coastal ecosystem.

What is red tide?

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) develop when excess nutrients enter the marine ecosystem, resulting in patches of algae to experience excess growth. HABs impose toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, selfish, marine mammals, birds and other species in the coastal and marine ecosystems.

“There is this presumption that when red tide occurs, it occurs everywhere and all the time,” Stumpf said. “It’s not everywhere and not all the time.”

Karenia Brevis, the specific photosynthetic organism linked with red tide, is found in the Gulf of Mexico. However, patches of Karenia Brevis have been found as far north as North Carolina.

“The organism is present in the Gulf of Mexico at all times but it has very low concentrations most of the time,” Stumpf said.

Stumpf explained Karenia Brevis swims up and down in the water to collect nutrients and light, resulting in high levels of growth when the water experiences calm periods.

“In the summer [the organism] starts growing and then with the wind shift in the fall it brings [in colonies of algae] to the coast and it accumulates,” Stumpf said. “At first, there is no bloom and there are only a few cells in the fall. Then during the winter, the winds push it back out into the Gulf of Mexico and it gets spread out and it’s harder to grow and either get diseased or outcompeted by other species.”

Why does this happen?

“[Karenia Brevis] is native to the Gulf of Mexico and we have excellent evidence there was severe red tide in Florida back in the 1840s,” Stumpf said. “Some of the descriptions from the early Spanish in Mexico describe conditions that indicate that HABs occurred back in the 1600s.”

Stumpf described last season’s red tide as “an exceptionally bad year,” but this year, Sarasota County has experienced a relatively small impact with low concentrations from red tide, mostly affecting the Southern part of the county.

Impacts of red tide

“Unfortunately, it’s almost like a laundry list of impacts [caused] by red tide,” Stumpf said.

Stumpf explained tourism was an industry directly impacted by red tide.

“If tourists hear about it, again and again, they might choose not to visit Sarasota or Florida beaches,” Stumpf said.

This can lead to a commercial impact on local businesses, depressing economic growth. If snowbirds stop visiting and supporting different local businesses then those businesses might not generate enough revenue to stay open and Sarasota could house fewer local businesses.

Additionally, the environmental impact is predominantly expressed through ecosystem disruption.

“You have a certain balance going on and then you have a bloom like last year comes through and suddenly hundreds of miles of the sea bed are dead,” Stumpf said. “Those will have to grow back and there is a lot of dead fish. If there are enough dead fish, sea birds can go hungry and starve to death. You end up with a whole range of feedback and it takes years to recover from something like what happened last year.”

Stumpf emphasized that the environmental impact of high concentrations of red tide causes severe disruption of the coastal and marine environment along with a slow recovery, which is not ideal.

Another byproduct of high concentrations of red tide is health impacts, commonly resulting in respiratory irritation.

“People with asthma or other respiratory illnesses can end up in an emergency room as a result of exposure,” Stumpf said.

Possible mitigation practices to better the impacts

HABs residing in the Gulf of Mexico cover a substantial range of the region, frustrating scientists researching mitigation practices because of the stretch of the affected area.

“The blooms, when they are in the Gulf of Mexico, cover a very large area,” Stumpf said. “There isn’t a treatment strategy that will get rid of them in the Gulf of Mexico which is realistic because it’s just too much area to cover.”

One short-term mitigation solution NOAA is working on is not mitigation in terms of completely eliminating the HAB but mitigation in terms of bettering the severity of the impacts.

“We’ve been working on improving identifying where the patches of bloom are and also what is the respiratory risk in individual beaches and throughout the day,” Stumpf said.

Red tide fluctuates in its concentration throughout the day, during certain times the area experiences low enough concentrations that it is safe for the public to enjoy the beach. NOAA is trying to indicate where and when the beach experiences low concentrations deemed safe dependent on a number of factors including wind patterns, tide patterns and current patterns.

“You have the potential in many numbers of mitigations that may help reduce the local impact so the ultimate question is does what they use directly kill other things or is it prohibitively expensive to employ,” Stumpf said. “Those are the kind of research questions that need to be investigated for mitigation.”