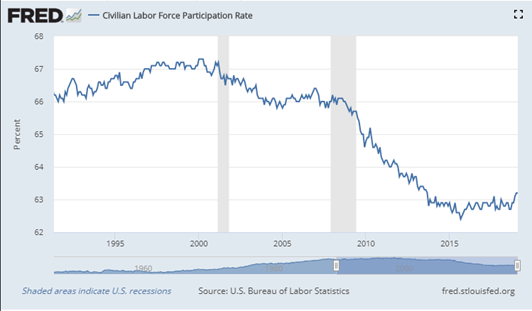

The Labor Force Participation rate decreased from around 67 percent in 2000 to 63 percent in 2018.

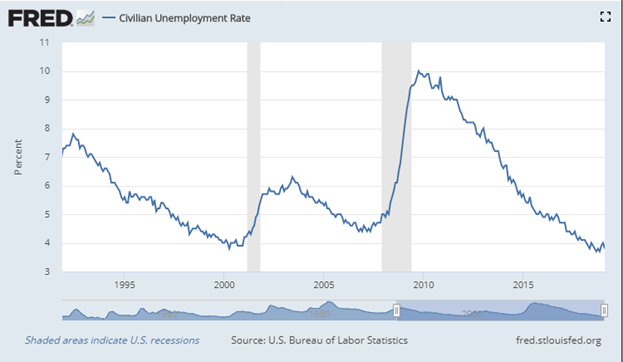

The official Civilian Unemployment Rate says that the U.S. economy has an unemployment rate currently under four percent.

Graphs courtesy of Federal Reserve of St. Louis (FRED).

After almost 10 years of quiescent markets steadily ticking upwards, 2018 became the year of volatility for financial markets, suggesting that a more general economic downturn is close on the horizon. Last year saw both a record-breaking high and historic low for the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones, and December witnessed the largest monthly percentage decline in stock prices since 1931, according to CNN. While many see a recession due after a decade of growth, others have pointed out that for most folks throughout the economy, little has recovered since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and the ensuing recession. If the economy has not recovered for most folks, then what will another recession bring? Professor of Economics Mark Paul discussed the health of the United States’ economy.

“The U.S. experienced a large economic decline starting in 2008 with the onset of the Great Recession,” Paul said. “Since then, we have witnessed one of the longest recoveries in history, however it has not fully recovered the economy. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects what economic growth should be. Currently, U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is roughly 15 percent below where the CBO thought it would be.”

While the United States’ economy has grown since the global economic and financial crisis, it has not recouped expectations, leaving GDP, productivity and wages unrealized. Paul mentioned that this dismal news of underperforming economic data may appear as a shock to those who have heard a lot, from two consecutive presidential administrations, about how the economy is at full employment and the stock market is reaching historic highs.

“Traditional measurements for unemployment fail to capture the actual employment situation in the U.S.,” Paul said. “If you look at labor force participation rates or employment to population ratios, for instance, it’s clear that those numbers are significantly lower now than in the 1990s and early 2000s.”

While U.S. productivity has increased steadily since the Second World War, wages have remained stagnant since the early 1970s. Modest wage gains and rises in official employment levels have not come close to breaking out of long-standing trends.

“If we were in a true full employment economy we’d see significant wage increases and this has not been the case,” Paul said. “It’s true that workers have experienced modest wage gains, but that rise is not significant to make up for decades of failed wage increases. Non-managerial wage earners haven’t seen significant increases for an entire generation. The recession has exacerbated levels of income inequality; the majority of the wage increases since the crisis have been accumulated by top income earners. We have not seen broad wage gains.”

The size of the pie keeps growing. The question is how much of that pie goes to the majority of workers, and the answer is not much, according to Paul. The average worker is worse off relative to those earning more.

Many worry about the consequences of automation on the size of wages. However, Paul points out that if automation was a significant force driving down wages, it would also drive productivity up, something which has not happened for the last decade.

“Productivity growth now is quite low,” Paul said.

The declines in productivity have shocked the academic economic community so much that some have wondered if the traditional ways to measure productivity are flawed. Paul thinks that while the measurements for productivity are flawed, just like orthodox ways to gauge macro employment levels, recent declines in productivity cannot be blamed on these methods of analysis. Moreover, he believes that the biggest thing to address low productivity and wage growth is large scale government investment in socially useful areas.

“Right now, firms are sitting on historically unprecedented levels of cash, primarily because they cannot find profitable areas of investment,” Paul said, which suggests that the idea that firms don’t have enough money to raise wages is provably false.

Paul sees the increasing dominance of the financial industry throughout the economy as a net negative for GDP, productivity and wage growth. One notable example is the phenomenon of stock buybacks, wherein corporations use profits and excess capital to buy their own shares of the company, effectively shrinking the pool of shares and increasing their value for the sake of shareholders. Companies have used buying back their own stock as a way to boost earnings to top executives, according to MarketWatch.com.

While the Federal Reserve has attempted to create inflation to spur economic growth since the Great Financial Crisis, low GDP and productivity and inflation growth has been the overwhelming condition for this decade. Aggregate inflation measurements like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) do not include prices for financial investments like real estate, bonds, stocks and life insurance, items that have been the chief benefactors to the massive capital infusions, called Quantitative Easing (QE), from the Federal Reserve. Financial markets have experienced unprecedented inflation, while the real economy has stagnated.

The stagnation of wages has not only contributed to income inequality but also has disproportionately affected African American and LatinX communities’ wealth, due to the sub-prime mortgage crisis and predatory lending practices to lower income people in the years leading up to the Great Financial Crisis, according to Paul.

“We saw that the equity that communities of color had in their house was disproportionately destroyed,” Paul said. “Right now Black wealth is about 10 cents to the dollar compared to white wealth in the United States.”

Paul has a clear answer for the lack of broad wage gains.

“Increasing productivity and GDP without reconnecting the link between productivity and wage growth will not help workers,” Paul said. When the next recession comes, “and it will,” added Paul, the majority of wage earners will once again find themselves in crisis. A tidal wave struck 10 years ago, and after all the devastation and unshakable calm, quiescent markets, another inflection point looms. If the next decade is more of the same, our economy will follow its current path further, pulling our political system along with it like a rag doll.

Information for this article was gathered from cnn.com, theguardian.com, usnews.com, bloomberg.com and marketwatch.com.