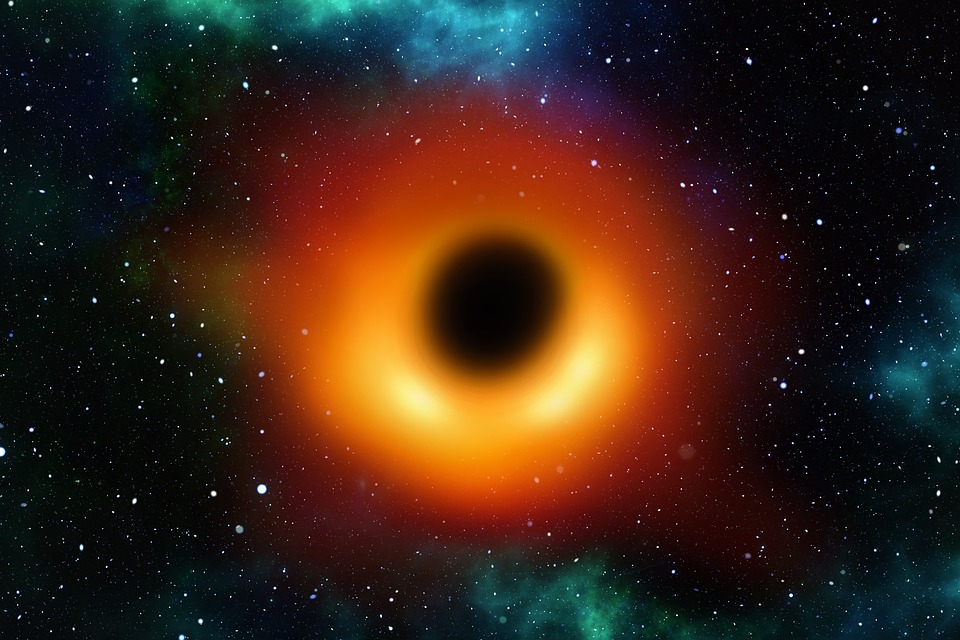

On Apr. 10, 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration released the first-ever image of a black hole. Over 200 researchers contributed to the project and worked for over a decade to accrue and analyze data from a global network of powerful radio-wave telescopes to produce the photo, which shows a bright orange and yellow ring formed as light bends in the black hole’s intense gravity. The black hole, named M87*, is 53 million light-years away from Earth and has attracted widespread attention on the internet.

Another photo that was taken at the moment the image of M87* was processed, which shows researcher Katie Bouman in front of a computer screen with hands clasped over her mouth, has also been a source of national excitement and discussion. The photo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science went viral, subsequently establishing Bouman as the face of the project as well as marking a historical moment for women contributions in STEM fields. Bouman helped develop the algorithm that sifts through the spate of data in the project.

At the same time, the photo of Bouman received extensive backlash online, where groups of men vehemently questioned Bouman’s role in the project. Amidst the groundbreaking achievement of imaging the first black hole, the harassment Bouman received online reminds students of the reality of gender discrimination in STEM, and accordingly begs the question: what is the state of gender discrimination in STEM at New College?

“There’s no doubt in my mind that we women are capable of accomplishing things [in science],” third-year and physics Area of Concentration (AOC) Tali Zacks said. “But it is hard to get through that mental block of ‘I can’t really do it because I’m just a girl.’”

Often credited as skillful teachers or mentors, women are not typically seen as influential leaders in the sciences—but of course, they are, and consistently have been.

“I didn’t learn anything [about how women can contribute to STEM] specifically from [Bouman’s accomplishment] happening, because I never believed it couldn’t happen,” second-year and computer science AOC Courtney Miller said. “What I did learn from is the reaction and how hard she was trolled—not just by internet trolls, but by respected members of the academic community [which happened because] we don’t expect women to be the ones leading the way on these kind of discoveries. That’s what left an impression on me.”

Despite the progress in equality across academia and the workplace over the past century, women remain dramatically underrepresented in STEM fields, including physics and computer science. While women earn over 50 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, only 21 percent of physics and 33 percent of astronomy bachelor’s’ degrees belong to women. Additionally, in 2017, only 26 percent of the computing workforce were women, and less than 10 percent were women of color.

“[Coming to America] as a postdoc, I was the only woman in the physics department at Emory [University],” Professor of Physics Mariana Sendova commented. “I said, ‘Wow, what has happened with this world?’ I see [the lack of women in STEM fields] as a huge imbalance. Here, at New College, I don’t think [gender biases are] so obvious as if you go to grad school, and for example, go in a physics department—then it becomes completely different.”

Though students at New College pride themselves on inclusive thinking, the slanderous attacks people have directed at Bouman online echo a deeply embedded and distressing attitude toward women in science, raising questions about just how much a discriminatory mindset pervades campus interactions.

“The only [discrimination I’ve experienced at New College is] what’s a big problem in computer science, which is the microaggressions from peers,” Miller said. “Sometimes I’ll feel like there are microaggressions or little things that happen, and I’m like, ‘You don’t do that to the other hacker-bros—you are treating me differently.’ Personally, [the microaggressions I’ve experienced from male peers] hurts a lot, and it’s something that you just kind of have to work through. There have been very recent things that have happened [that were] very hurtful and not okay, and people in the department are complacent [about these situations of discrimination] because this is not something we address.”

Professor of Human Centered Computing Tania Roy shares similar frustrations with experiences of microaggressions and unconscious biases, and commented on the unconscious biases dealt with prior to arriving at New College.

“[Experiencing microaggressions are] challenging as they are subtle and sometimes you ask yourself if this is actually happening or you are over analyzing a situation,” Roy said in an email interview. “There have been situations as a graduate student and a faculty [member] that I have had to deal with, for example comments like, ‘You got this because you are a woman,’ and on the flipside I have been in classrooms where professors and fellow students don’t pay heed to your suggestions. This is where imposter syndrome keeps creeping back in and they were moments of struggle.”

Imposter syndrome is no stranger to students at New College. Still, sexist prejudices ingrained in the public mindset seeps into student mentality, inevitably influencing the way non-male students participate in STEM fields.

“New College is intrinsically a very open, hippy, diverse, amazing place,” Miller noted. “Our computer science department also happens to intrinsically be open and filled with mostly inclusive and diverse people; then we sometimes do get [students] that are reminiscent of the problematic behaviors that damage the egos of minorities. Other schools don’t have the privilege that we have, where [male students] are the minority; at most schools, that’s the majority, so they have to address [gender discrimination]. I feel like here, we almost have a problem where we don’t most of the time have to address it, so when the one hacker-bro comes along, we kind of just say, ‘Oh well, we have a really good department in general,’ but that’s not necessarily because the department has done anything [to] make these people accepting, open or diverse.”

The sexist backlash in response to the pioneering work to create a black hole image demonstrates the hostility women and non-male genders receive in the sciences.

“I remember in high school my friend and I were taking evening classes to prepare for the exams,” Sendova commented. “There were only boys there, and you get absolutely depressed when you see them thinking quick and going to the board and solving these problems. I told my girlfriend: what are we doing wrong? This is difficult to do, and easier to say, but you should just ignore [male students] because a lot of men project strong-confidence [and] knowledge. I see this all the time—I see male students who talk absolute nonsense, but they talk it with confidence. Before, when I was at their age and someone was talking to me like this, I would say, ‘Oh you’re great,’ but now, I can see that sometimes, it’s gibberish.”

Along with focusing on personal development, Roy notes that acknowledging the distressing nature of gender discrimination can serve as a motivator to continue working toward increased involvement of women and non-male genders in the sciences.

“[Experiencing gender discrimination] does get overwhelming sometimes; I have always struggled with imposter syndrome and still do,” Roy said. “However, with experience and supportive colleagues, I have learned that my contributions and voice have the potential to add value. This has taught me to be assertive in situations and lean on my support network if I need advice.”

The accomplishment to look light-years away from this galaxy does not go without instances of gender discrimination of women and other non-male scientists. With the exponential progress taking place in science and technology, there is still an archaic view of women roles that highlights the importance of acknowledging sexist prejudices, including within the scope of New College where students generally pride themselves on tolerance and inclusivity.

“There are problems here, and sometimes I experience things from specific people,” Miller said. “But in general, this is a great environment to be in, relatively speaking, so sometimes you do get lulled into a sense of security that most people are really chill, but [the sexist backlash to Bouman’s work] reminds you that that’s not true. It doesn’t necessarily change what I think I can do [as a woman in computer science], but it’s a sobering moment, where [sexist prejudices are] something that’s still very important and not a novel concept that needs to be further built upon.”

Information for this article was gathered from uis.unesco.org, aip.org and ncwit.org.