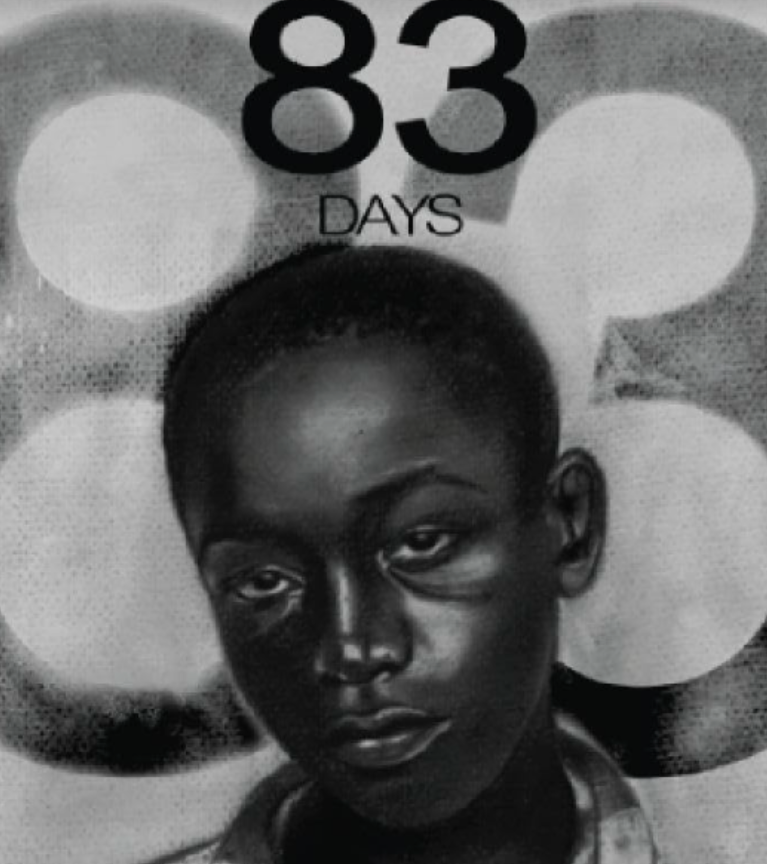

In 1944, a 14-year-old African American boy was wrongfully executed for a crime he didn’t commit. Seventy years later, his case was vacated by the state of South Carolina. Today, his story is told through the award-winning short film 83 Days, written by Ray Brown and directed by Andrew Howell. The film is available to stream on video on demand. The filmmakers spoke with the Catalyst about the film and its creation.

Scrolling through FaceBook one day, Brown said he came across a headline about George Stinney Jr. being killed in South Carolina. Stinney was sentenced to death by electrocution for the rape and murder of two girls, a crime Stinney did not commit.

As he looked further into the story, Brown realized this was an old case. “Why has no one heard about this?” Brown recalled asking himself. “Why was African American history not being shared?”

Thus the journey began. Brown worked with his attorney to bring forth evidence proving Stinney’s innocence. They faced heavy pushback from the state of South Carolina. After being turned away by the South Carolina Archives, Brown had to go as far as to hire a white woman to get information. This is how he was able to get the location of a cemetery where the Ku Klux Klan lynched and buried victims.

“This was a situation where I realized I had a voice and was obligated to use it,” Brown stated.

With this information available, Brown contacted the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). When he finally received a call back, it was to meet in Charleston in November 2013. A hearing was conducted the next month, but deliberation continued for a year. During this time, Brown said, the cemetery was cleaned up and any evidence of it removed from the internet.

A decision to vacate Stinney’s case was made in December 2014. But there’s a stark difference between vacating and exonerating a conviction.

“The reason [for vacating] was because they were afraid,” Brown asserted. “They vacated his sentence instead of exonerating it. Vacated because [exonerating] it would’ve meant they admitted to the mistake, and have to give back to the family. They vacated on the premise of civil rights violation.”

Even with all the work Brown and his team put into this case, he emphasized that he’s far from finished with it. “The journey for me on this project was harsh. I don’t talk about it much but I got threats, my phone got tapped, I was under federal investigation,” Brown told the Catalyst.

Brown decided to write a narrative piece sharing Stinney’s case. A mutual friend introduced Brown to filmmaker Andrew Howell and Brown shared his screenplay. Howell and his wife, Summer Howell, loved the piece but thought it would be easier to produce a short film rather than a feature-length, meaning it would have to be significantly shortened.

Brown said he was open to this idea, but was adamant on ensuring there would be a beginning, middle and end. Three weeks later, Summer was able to do just that. They began putting together a cast and crew to begin filming.

83 Days Director Andrew Howell, who also spoke to a Catalyst representative, gave insight on how the filming process went, along with what he hopes to include in a possible full-length feature film, should they secure necessary funding.

Howell said he believes “people are most educated when they are entertained.” With this in mind, he chose to move forward with a historical narrative format.

“The execution scene is high impact,” Howell said. “There are lots of metaphors tapping into religious beliefs. With the prosecutor on the left, the priest on the right and Junior in the middle, it portrays Christ on the cross.”

Howell recalls that there were extensive meetings with all departments to ensure the story was displayed accurately. Howell himself spent a lot of his free time preparing to direct actors, as his previous experience was in photography directing.

With all this preparation, the film was shot in only three and a half days. The cast and crew had to work quickly as they had limited time in the rented locations. “The film would not have been made if it wasn’t for everyone coming to work pro bono on this project,” Howell remarked. This makes it all the more important for viewers to support the release of the film on demand.

The 83 Days team was able to make the film affordable to stream, but are still on the hunt for funding to create a feature-length film. “A feature will give us the best opportunity to speak to the mind,” Brown stated. “We were able to successfully tell the story in 29 minutes. But there is still so much story to tell.”

Howell touched on some aspects he wishes to include in the full-length project. Scenes showing the aggressiveness of the violence or when the girls are found would be included. Additionally, there would be an emphasis on how a community in the 1940s came together after a tragedy.

“The fundamental problem with the short film is that it makes people angry and sad which isn’t the point. In the feature film, there are elements of faith, hope, love, forgiveness and relief from agony,” Howell commented.

What started as a passion project for Brown quickly took fire and blossomed into a major milestone for civil rights activists and those pushing for change in the American criminal justice system.

“My goal now is to tell his story,” Brown stated. “Not to win Oscars or Golden Globes. It’s to get his story out there so the world knows.”

83 Days was awarded Best Short Film by the Tampa Bay Underground Film Festival (2018) and the International Houston Black Film Festival (2019) but its impact goes beyond the accolades. Howell said he does not regret any of the work he did for the film and describes this valuable story as “the culmination of my life’s work on a screen.”

“I have no doubt in this story,” Howell said. “Those who are patient will win.”

Thank you for this informational article! More people need to give time to black writing and media.