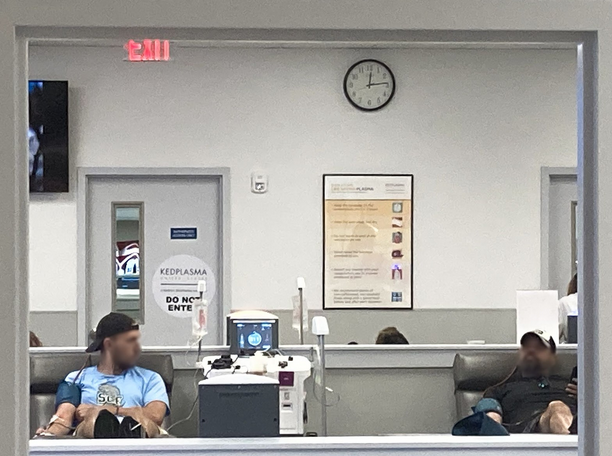

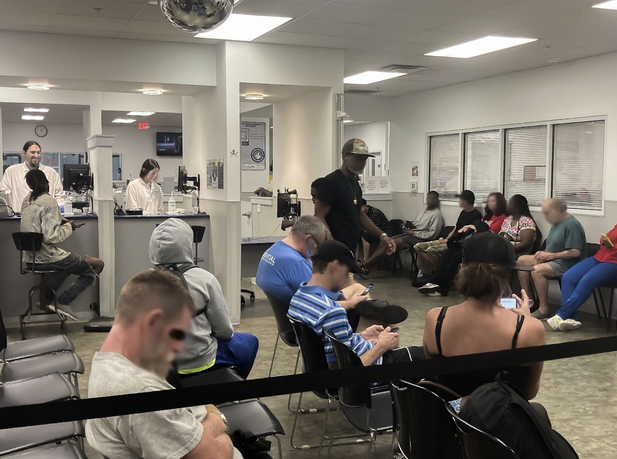

There’s a jittery and anxious energy to the air. The music is alternating between high-energy jazz and Christmas carols belted over the intercom. A groundswell of regular plasma donors are jostling between black rope lines, hastily filling out informed consent forms at one of the many self-check-in kiosks, or slumped over on the dark plastic chairs that line the waiting room from wall-to-wall.

The donors are eager to reach the front of the line. The three-to-six hour wait is hard to bear—but better than walking away unpaid. Once at the front, their vitals are captured by unlicensed physicians—instead of name tags, the coats hold the corporate insignia of the facility upon their pocket. So long as the donor’s vitals haven’t dropped between the twice-a-week blood drawing sessions, they are cleared to proceed with their paid plasma donation.

“I just can’t do it anymore,” Richard gritted in an interview taken just after he refused service and left the building. Richard is a former regular of the plasma donor industry whose full name is withheld for confidentiality.

“It just can’t be good for your health,” he continued. “[But] people are desperate for money, like myself, and this is what we ended up doing to try to make ends meet or get what we need for the day.”

This was the scene from one of several plasma donation facilities that operate in densely populated and low-income parts of the Bradenton-Sarasota area. These facilities are offering substantial sums of money ranging between $50 to $100 in exchange for the plasma of donors who participate in the program, with special incentives in place to encourage donors to donate twice a week. The industry itself has burgeoned in the U.S. precisely for this reason: most other nations in the developed world restrict the pace of regular donations to no more than once every two weeks, meaning the periods between plasma extractions are typically four times longer in other countries than they are in the U.S.

It’s in this context that the resurgence of corporate plasma donation centers across the U.S. has unfolded. Since 2005, the number of plasma donation facilities has doubled, the number of plasma withdrawals collected at these facilities has tripled and the plasma medical market size has skyrocketed from $4 billion in 2008 to over $30 billion in 2021.

Yet, none of the plasma donated at these facilities will be used for the life-saving transfusions that many of the industries’ advertisements imply. As per Food & Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, hospitals and non-profits like the Red Cross are forbidden from using plasma from privately owned for-profit plasma extraction centers due to ethical considerations and the increased risk of supply contamination. Thus, all of the plasma collected from donors at donation facilities are distributed to for-profit pharmaceutical companies, who use it to produce specialty drugs that require human plasma in their manufacturing process.

Plasma corporations were publicly reviled between the late ’70s and early ’90s due to widespread scandals involving unsafe drawing conditions and contaminated pharmaceuticals that resulted in thousands of hemophiliacs contracting Hepatitis C and HIV. The industry has since been reintroduced to the public under a new auspicious branding campaign—one that leans on the emotional catharsis of “saving lives” with each donation.

Plasma donation facilities are strategically placed and systemically advertised to reach individuals struggling with enormous financial burdens. Over 80% of plasma facilities are located in poor neighborhoods. Even students are a prospective market—one advertisement pinned up at the New College Caples Campus sculpture lab asks, “Need money for art supplies?” with an advertising card below it answering “donating life saving plasma has never been more rewarding.”

Indeed, many donors were happy just to be able to earn income surpassing the minimum wage, while also feeling they are able to help others in need. Between wage stagnation, rising rent costs, inflation, medical debt and other burdens, many donors indicated that they wouldn’t be able to make ends meet without the twice-weekly blood withdrawals that fuel the ever-increasing demands of the pharmaceutical industry.

“It’s saving lives, where I think we could save or help seven to eight people per donation,” regular plasma donor Monica shared, recalling the slogan adorned on many of the facility’s signs. “I’m an Uber and DoorDash driver and I can’t make 50$ in three hours. I was worried about it when I first got there, about whether I needed the plasma or not. But the body regenerates plasma. And if I did a little something to help somebody out a little, and plus get a little kickback for myself, why not?”

In certain cases, it proves true that the plasma extracted at these facilities goes on to create important medicines owned and sold by the pharmaceutical industry, such as immunoglobulin. For those with immune disorders and other chronic diseases that require plasma-based medical therapies for treatment, the issue of whether there’s a shortage in the plasma supply can become a matter of life and death.

According to the Immune Deficiency Foundation, persons who rely on these medicines are even fearful of journalistic articles that further stigmatize plasma donation.

“There’s a collective groan and a growing sense of unease when a piece like this appears because of its potential to further stigmatize a market badly in need of more donors,” one piece from the foundation wrote.

With the benefits that plasma-based pharmaceuticals can bring to the immunocompromised in mind, it is easy to see how this industry can be rationalized as not only benevolent but crucially necessary. But the situation should be examined by more than just its individual parts. Many of the people who donate are living in a system that impoverishes them through the methodical suppression of their wages and increases to the costs of basic living conditions. That same system pushes them to sell their own vital essence to massive pharmaceutical corporations just to survive.

It should also be noted that 62% of bankruptcies in the U.S. are from medical bankruptcy. Many of the people donating and selling their plasma are doing so to cover the exorbitant and outrageous medical bills exploitatively hoisted on them by the very same industry.

“Times are tough, and rents are through the friggin roof right now,” Richard admitted. “You can’t even rent out a place without $2,000 a month including your utilities and electric. And everything else involved is pushing the humans out to the streets. And that’s exactly where we’re at right now.”

Further, what exactly is driving the increase in the plasma industry to begin with? It seems profoundly unlikely that the number of people with immune-compromised diseases has tripled in the last decade alone. Indeed, mainstream medicine has been making steady advancements in a variety of treatments that are now dependent on plasma-based technology. Research conducted on plasma-based medicine is now a wide-spanning and multi-disciplinary field, with new pharmaceutical products utilizing plasma launching every year. This expansion into plasma-based medicine may be because of the revitalization of the plasma industry in the U.S. and the plentiful supply of regular donors that can be gathered from the countries’ low-income populations.

“Today, a significant portion of immunoglobulin G usage is in specialties outside of immunology, such as neurology, hematology, oncology and rheumatology,” industry insider Eddie Munoz wrote.

There’s also the issue of how twice-a-week sessions and poorly trained staff impact donors at these loosely regulated facilities. The plasma donation industry markets the procedure as being completely safe. Yet, donors are made to review dozens of documents informing them of the potential risks and side effects of making a plasma donation.

Additionally, the people who donate are incentivized to lie on these reports. Whether it be on specific medical conditions, drug use or adverse reactions from previous plasma withdrawals, donors reliant on the extra income are motivated to continue with their donation regardless of the risks, sometimes even drinking extra water beforehand just to meet the 115 lb weight requirement. The white-coated personnel trained in-house who derive their authority from a single medical director were likewise said to be lenient so long as donors pass basic vital tests, with few repercussions for malpractice.

“My fiance’s fainted several times, and I’ve felt very less energetic when I’ve left here several times more recently as I’m getting older, and your body’s breaking down,” Richard said when asked whether he’s seen adverse reactions from plasma donation. “I had a friend that actually had his blood transferred back into his body and it was not going into the vein, it actually was going into the muscle tissue. They blew his arm up to three times the size of what it normally is. And they actually told him that’s not their fault. They just kind of blew him off. They acted like they didn’t know who he was. They treated him [with] real disrespect.”

“He got an attorney involved and somehow it didn’t work,” Richard continued. “It didn’t pan out for him. But I don’t know why it didn’t. But you know, they kind of protect themselves for those reasons. And he was left with a pretty bad arm for three months.”

This isn’t an uncommon complaint either. Online reviews posted to the facility’s official Google page echo these systemic issues.

“The phlebotomists here need proper training,” donor Justin Capen reported online. “They’ve messed my arm up every time I’ve been here along with other people that I have spoken to.”

“I was there for two and a half hours,” donor Sage Sarrazine wrote. “They were understaffed. An employee quit while I was there. I was stuck improperly, and when I found out that the machine they connected me to wasn’t working right and requested to be disconnected early, I was given nothing for my time, despite them claiming to pay an amount proportional to the amount you donate.”

After reaching out to the management of this particular facility for comment on some of the complaints that donors levied, the on-site quality assurance manager Steven Olive gave a response in an on-the-ground interview.

“In any service industry, employees go through service training,” Olive said. “Our facility is no exception. At times issues do happen. That happens in any industry. And of course, we want to be as friendly and professional to our customers as possible.”

Olive went on to explain that he thinks complaints are more likely when the rooms are packed, as they were at the time of the interview, because of the frustrating wait times. The coronavirus pandemic led to a staffing shortage and the industry has yet to fully recover from it—but either way, former customers have made complaints for reasons other than crowded queues.

When asked why he wouldn’t be returning to the plasma donation industry again, Richard gave a charged, heartfelt response.

“Well, it’s five donations at $115 a shot, but my wife’s a little bit more important than that money,” he said. “I’m beginning to go to work for myself. However, it’s hard to win at that. But [I’d rather do that] instead of waiting here in this ridiculous line to have my blood sucked out of me and do all that bullshit waiting for three-quarters of a day’s work.”

I am a plasma donor. The facility I utilize does not have the issues that are stated in this article. My wait times are relatively short (10-15 minutes at a maximum). The phlebotomists are very skilled and friendly. It’s too bad some people have a negative experience at the facility they use. All facilities are not like the one described in this article.