It’s not really about Julian Assange.

If you own a cell phone, have ever visited a social media site or occasionally walk past your mom watching CNN, you’ve heard the spiel of fall 2020: our freedom is under attack, and it’s up to you and Joe Biden to save us all. Meanwhile, the most important press freedom case in a generation has been unfolding across the pond, all but unmentioned in the mainstream media.

The founder of Wikileaks, Australian-born Julian Assange, has been charged under the United States’ 1917 Espionage Act for “unlawfully obtaining and disclosing classified documents related to the national defence”—the first time the act has ever been used to punish the publishing of information—and one count of “computer misuse.” Assange, whom Biden called a “high-tech terrorist” in 2010, faces a possible lifetime sentence of torture and imprisonment if extradited to the United States.

The cruelty Assange has endured and has yet to abide at the hands of the government is an unthinkable tragedy, but only hints at the dystopian horrors in store if his extradition is upheld. Assange’s trial, which hinges on the one count of “computer misuse” (their most defensible charge), is a sad farce: no government is interested in punishing him for a (failed) attempt to crack a password. Assange was instrumental in exposing their corruption and unforgivable crimes against humanity, and they want to make an example of him. Most importantly, they want to set the global precedent that sharing classified information is a capital offense, and there is nowhere to hide from a government that wants you to pay the price. They want to ensure that nothing like Wikileaks’ Iraq War Logs and Cablegate is ever allowed to happen again.

In 2006 Assange and others established Wikileaks, an international nonprofit allowing whistleblowers to anonymously leak suppressed documents of historical importance. Their stated mission is to “bring important news and information to the public… so readers and historians alike can see evidence of the truth.” It is hosted on several computer servers in countries like Sweden, which has laws prohibiting governments from uncovering journalists’ sources. Wikileaks has published a plethora of documents previously unavailable to the public, shedding light on Tibetan dissent in China, extrajudicial executions in Kenya and membership of the far-right British National Party, to name a few. But it didn’t become a household name until 2010, when it began publishing material from U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

In April 2010 Wikileaks published Manning’s Collateral Murder video, which showed U.S. soldiers in Iraq execute 18 people from a helicopter, firing 30 mm rounds indiscriminately into a passive crowd in New Baghdad. Among them were Namir Noor-Eldeen, who was taking photographs for Reuters news, and Saeed Chmagh, who was driving him. The U.S. government had previously denied the video’s existence when Reuters sent a Freedom of Information Act request.

“140610-Z-AR422-003” by New York National Guard is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

“Look at those dead bastards,” says one of the soldiers; the other responds “Nice.” They laugh. Civilian Saleh Mutashar pulls up in a van to help the injured, including Chmagh. The pilot requests permission to attack the van, obtains it rapidly, and opens fire, killing Mutashar and badly injuring his children, ten year old Sajar and five year old Doaha. They were on their way to school.

Collateral Murder was a global media sensation. Federal officials and some news outlets made a tepid attempt to invalidate or discredit the video: Obama’s press secretary, defense secretary, The New York Times and The Washington Post emphasized the supposed dangerousness of the soldiers’ victims, and that the video was taken out of context—but were largely unsuccessful. The footage was too real, too disturbing. I don’t know what it looks like when human beings are sadistically eviscerated with bullets the size of my forearm—I can’t bring myself to actually watch it—but I imagine it’s hard to spin as glorious and necessary.

The Guardian said Collateral Murder was “heralded by some as the most important revelation since Abu Ghraib, and challenges not only the effectiveness of the US military’s rules of engagement policy, but also the integrity of the mainstream media’s coverage of similar incidents.” The video came out shortly after the Pentagon was forced to admit to their cover-up of a horrific civilian massacre in Afghanistan that involved digging bullets out of women’s bodies with their fingers.

Collateral Murder put Assange firmly in US crosshairs—it was then that the US Department of Justice began the investigation of Assange that would ultimately result in his 2019 arrest. Manning was arrested in May 2010, just a month after the video’s release, but Wikileaks continued to publish material received from her.

Next came the Afghanistan War Logs, which The Guardian called “a devastating portrait of the failing war in Afghanistan, revealing how coalition forces have killed hundreds of civilians in unreported incidents, Taliban attacks have soared and NATO commanders fear neighbouring Pakistan and Iran are fuelling the insurgency.” After this the US threatened Assange with the 1917 Espionage Act and Computer Fraud and Abuse Act for the first time, in an attempt to prevent him from releasing the remaining documents (in the end, despite recruiting an ex-Wikileaks employee that provided several of Assange’s hard drives, the FBI were unable to find any proof of the charges levelled against him).

Undaunted, Wikileaks subsequently published the Iraq War Logs, the biggest leak in the military history of the United States, which contained records of many atrocities (and violations of international law) committed by US soldiers and contracted units. It revealed 15,000 previously unknown civilian deaths to the public and Iraq Body Count Project, which calculated that “over 150,000 violent deaths have been recorded since March 2003, with more than 122,000 (80%) of them civilian.” Among other important revelations of international affairs, the Iraq War Logs proved that abuse and murder of civilians and combatants alike is not an exception but the known rule of the US army and its partners in the Middle East.

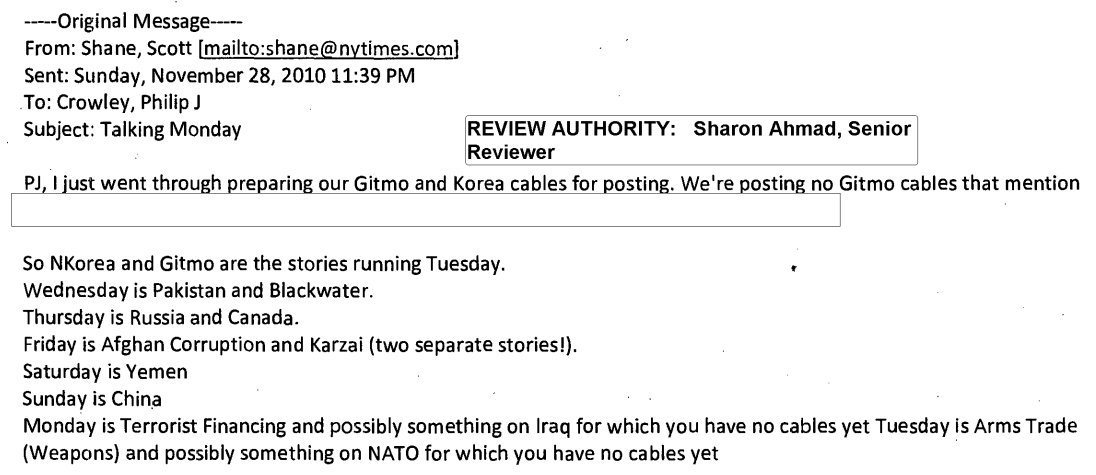

Next, Assange published the Guantanamo Bay Files, revealing the United States’ torture of known innocents from age 14 to 89. Then came “Cablegate,” the release of a quarter million US diplomatic cables sent and received from 1966 to 2010. Its revelations are tremendous in content and scale.

“The internal communications of the US Department of State are the logistical by-product of its activities: their publication is the vivisection of a living empire, showing what substance flowed from which state organ and when. Only by approaching this corpus holistically – over and above the documentation of each individual abuse, each localized atrocity – does the true human cost of empire heave into view,” Assange wrote of the Cablegate files.

Prior to its release, when it became known that U.S. diplomatic cables would soon be seen by the public, governments around the world braced for impact. Many attempted to collude with each other and media outlets to minimize the leak’s impact. Assange sent a letter to the U.S. State Department inviting them to “privately nominate any specific instances (record numbers or names) where it considers the publication of information would put individual persons at significant risk of harm that has not already been addressed.” The U.S. declined to offer any, responding, “We will not engage in a negotiation regarding the further release or dissemination of illegally obtained U.S. Government classified materials.” Assange, in turn, said their response “…leads me to conclude that the supposed risks are entirely fanciful and you are instead concerned to suppress evidence of human rights abuse and other criminal behaviour.” The New York Times intercepted the cable files prior to the public leak and sent their content and release schedule to Hillary Clinton’s State Department, who disseminated it to the other countries, ostensibly so they could prepare media censorship or damage control.

Then-Secretary of State Clinton was at the forefront of the United States’ effort to silence Wikileaks and remains particularly vocal against Assange; she maintains (sans evidence) that he’s a Russian spy and commented on Assange’s 2019 arrest that he “must answer for what he has done.” The Cablegate leak revealed that Clinton had ordered an espionage campaign against United Nations leadership—as described by CNN, “In the July 2009 document, Clinton directs her envoys at the United Nations and embassies around the world to collect information ranging from basic biographical data on foreign diplomats to their frequent flyer and credit card numbers and even ‘biometric information on ranking North Korean diplomats.’ Typical biometric information can include fingerprints, signatures and iris recognition data.”

In addition to U.S. espionage against United Nations and other world leaders, Cablegate exposed massive government corruption in countries around the world. Its revelations were particularly impactful in North Africa and the Middle East, where some countries with weaker centralized governments rely on the promise of Western military power to crush populist revolutions. Cablegate was a catalyst for the tidal wave of radical anti-authoritarian uprisings that swept across the region in the early 2010s known as Arab Spring. It began in Tunisia: the people were already aware that their government was deeply corrupt, as Cablegate laid out in detail, but the leak revealed the U.S. had long been faking its support for Tunisia’s ruling powers: “The U.S. campaign of unwavering public support for President Ali led to a widespread belief among the Tunisian people that it would be very difficult to dislodge the autocratic regime from power. This view was shattered when leaked cables exposed the U.S. government’s private assessment: that the U.S. would not support the regime in the event of a popular uprising…Within one month, Ben Ali became the first Arab leader to be swept from power in the ongoing democratic movements in the region.”

The early 2010s saw a global wave of anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist rebellions: for the U.S. it was our Occupy Wall Street movement, which was greatly influenced by Arab Spring. This—all of this, from Wikileaks’ first expose with Collateral Murder to the massive popular uprisings sparked by Cablegate—is why the U.S. is determined to see Julian Assange behind bars, and why all of our freedom depends on his.

You may have noticed that “What You Should Know About the Assange Extradition Trial” is not actually about Assange’s extradition trial. The U.S. government has no shortage of lies, and I see no point in repeating them; that’s what the mainstream media is for. I also have no illusions that the legal system of the U.S., U.K., or anywhere else is even capable of operating fairly or dispensing “justice,” but even those who do—such as American lawyers who want Assange behind bars over at the appropriately named “Lawfare Blog”—are aghast at the extradition’s kangaroo court. For some reason (officially, the COVID-19 pandemic), journalists were given ridiculously limited access to it. Suffice to say that the trial, during Assange was placed in a semi-soundproof glass box “for his own protection” (when court is not in session, he’s imprisoned in social isolation), was a spectacular affront.

The U.S.—and British, Swedish, and, after a hefty bribe from the U.S., Ecuadorian—governments all have reasons for prosecuting Assange that are not about his massive whistleblower leaks, and they are all lying. Washington began hunting Assange after he first exposed their war crimes in 2010, and now it seems that they have finally got him. We’re 10 years out from the publication of the Iraq War Logs, and the only ones who’ve been legally punished for the U.S.’s horrific war crimes are the two people who exposed them.

Wikileaks’ revelations differ from other journalistic whistleblowing only in scale and impact. The government’s farcical reasons for indictment include such standard journalistic practices as protecting source identities and encrypting files, effectively criminalizing investigative journalism. Fearing First Amendment protections for journalists (although the U.S. is attempting to argue the First Amendment doesn’t apply to Assange, since he’s not an American citizen), they’re trying to secure his extradition by charging him with conspiracy to commit a computer crime. The selective prosecution of journalists with cybercrime laws is a well-documented tactic of authoritarian governments to silence dissent—U.S. treatment of the press is now going the way of Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, Jordan and Tunisia. Brazil, in turn, has already taken inspiration from the American prosecution of Assange: Bolsonaro, whose corrupt election was exposed by Glenn Greenwald formerly of The Intercept, charged Greenwald for cybercrimes in January with an argument virtually indistinguishable from the Trump administration’s current prosecution of Assange.

So it’s clear why “what you should know about the Assange extradition trial” is also not really about Julian Assange. While revelations from Wikileaks led to massive popular uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East, the Western conversation about Assange is seldom more than partisan, individualist drivel. It doesn’t help that Assange allegedly attempted to secretly aid the 2016 Trump campaign, which I’d argue he’s been more than punished for in dramatic irony alone. I believe this allegation, and think it reflects quite poorly on Assange’s intelligence and personal integrity. It’s also largely irrelevant: whatever Assange’s personal motivation, the leaked Podesta emails that damaged Clinton’s campaign were real and important, Assange is not a “Russian agent,” as the McCarthy democrats insist, and his integrity and intelligence are thankfully not on trial here (show me a white man who’d walk free from that case).

Assange has been heralded as a hero by many on the “right”, and Manning by many on the “left,” which makes about as much sense as these things usually do. I have no interest in lionizing or demonizing Assange, Manning, or anyone else. From the murky, poisoned chalice of personal information we have about either of them, I think it’s safe to conclude they’re both pricks, at the very least, with a history of disrespecting women. But as usual, alleged violence against women is used only as a political ploy to smear character and justify punishment for what the powers that be actually care about: in this case, exposing U.S. war crimes.

Luckily, determining one’s position on the Assange extradition trial is actually very simple, and you don’t need to read any leetspeak chatlogs or blogs of questionable ideological basis (I did that part for you). Do you believe in free press? If your country were doing war crimes, would you want to know? Do you think the internet should be a place for free information-sharing, rather than just a profit and surveillance machine for the digital military industrial complex? Congratulations! If you answered yes to any of the previous questions, you now have to defend Julian Assange from the imperio-capitalist Powers That Be, and also your aunt with the HRC bobblehead. I know what I’m bringing up at Thanksgiving.

Hey are you just like not gonna mention at all that Julian Assange also violently assaulted 5 women and is a rabid conservative? cuz it kinda seems like you’re ignoring that incredibly important detail.

Damn.

Hey just wanted to point out that your source for Chelsea Manning disrespecting women comes from a radfem anti-trans site that doesn’t even have screenshots of the supposed interaction. The only other source I could find backing it up was from Daily Mail, which is a tabloid often criticized for its lack of reliability. Just letting you know so you don’t unwittingly propagate transphobic misinformation. Otherwise nice article!

Thanks! For me, sourcing something isn’t an endorsement of whatever ideology’s behind the website. I believe there’s conservative libertarian sources in this article as well. You’re correct that Manning’s assault’s had very little publicity— I sourced it from that site because it was the only place I could aside from the daily mail or the actual full chat log, which is a big GitHub file thats also difficult to find online. You can draw your own conclusions as to why the chat logs and that particular comment are so buried on the Internet, but it’s not bc that comment wasn’t made— you’re welcome to read it yourself https://gist.github.com/Aupajo/452734

cheers