SUBMISSION by Cassie Manz

This article contains information that may be troubling and upsetting to read. It discusses the brutal murder of men, women, and children by the Nazis during World War II. Mentions of concentration camps, deathly gas and execution.

Forty minutes northwest of Prague, there are the remains of a town that once was. There is a sliver of a stone wall, what once used to be part of a farmhouse. Otherwise, the green fields stretch before you, completely empty. If one stumbled upon the area and had no knowledge of the land’s story, it might simply seem like a quiet park.

In June of 1942, Adolf Hitler’s forces brutally wiped out the town of Lidice, an act known as the Lidice Massacre. Hitler wanted this to serve as a warning to the Czech people, that resistance to the Nazi occupation would not be tolerated. The soldiers who carried out the orders even filmed it, as evidence of what they were capable of.

Why Lidice?

In 1938, four years before the massacre, Germany, France, Italy and Britain signed the Munich Agreement, allowing Hitler to occupy the Sudetenland, the outer edges of Czechoslovakia where many Germans who had left the Third Reich lived. Many Czechoslovaks disliked the Munich Agreement because they believed it would eventually lead to Germany annexing all of Czechoslovakia. On March 14, 1939, Slovakia declared its independence from Czechoslovakia, quickly becoming a Nazi puppet state. On March 16, Hitler invaded Bohemia and Moravia, proclaiming it a Protectorate of Germany and marched successfully into Prague.

After the successful occupation of Czechoslovakia, Hitler appointed security police chief SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich as Reichsprotektor in 1941 to quell the growing anti-Fascist resistance movement. Heydrich was a powerful figure of Nazi Germany and in 1942 a plot was hatched to assassinate him. The plan was called Operation Anthropoid. Two Czech patriots, Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik, along with the Polish forces in Britain, carried it out.

After the assassination, Hitler demanded mass executions of the Czech people. However, Heydrich’s subordinate SS Gruppenführer Karl Hermann Frank suggested that the Nazis look for the assassins first. The Germans invaded 5,000 towns and arrested more than 3,000 people, 1,344 of whom were sentenced to be executed. Fortunately, the threat never materialized for many of those sentenced.

Then, a “suspicious” letter was intercepted that roused ideas of a connection between Heydrich’s assassination and the Horák family living in Lidice, who had a son serving in the Czechoslovak army in Britain.

The suspicions were wrong. Investigations and a home-search produced no evidence that the family had been involved in the plot. Still, Hitler ordered the town to be wiped out, as avengement for Heydrich’s death. Specifically, he commanded that all adult males were to be executed, all woman to be immediately transported to concentration camps, all children suitable for “Germanization” were to be placed with German families in the Third Reich and lastly the village was to be demolished and the area leveled.

On June 10, 1942 the men of Lidice were rounded up and executed against the wall of the Horák farm. Mattresses were placed behind them on the wall so the bullets would not ricochet. One hundred seventy-three men were killed that day. The women and children were taken to the gymnasium of the village school.

After three days, the Nazi forces separated the children and women. The children were loaded into buses. The ones selected for “Germanization” and babies under one year of age were sent to families in the Third Reich. The other children, 82 of them, were sent to the extermination camp at Chelmno where they were gassed to death in specially-adapted trucks. The soldiers had told the women that they would see the children again shortly. The mothers and children were distraught at being separated but the Nazis ripped them apart, threatening to shoot the children if the mothers did not let them go. The mothers eventually complied, believing that they would see them again, as the soldiers promised. For most of the children, they never did.

Nearly 200 women were sent to the Ravensbruck concentration camp, from which few returned. A few others had been executed along with the men on the first night.

Once everyone was gone, the soldiers burned all the houses and bulldozed the ruins flat. They dug up the graves in the village cemetery and destroyed the church. They filled in the pond where villagers had once canoed on a warm Spring day, diverted the direction of the stream and uprooted all the fruit trees. After they were done, they put a fence around the territory warning any passerby not to enter. Out of the 503 village inhabitants, 340 people were murdered by the Nazis.

The area where Lidice once stood has since been turned into a memorial, with a museum, rose garden and several monuments and sculptures throughout.

In the museum, there is a video of the survivors of Lidice, mostly children. They recount their memories of what happened on that fateful day in June. Many children who were sent to German families were not allowed to speak Czech and they were so young that they soon forgot how to. One woman remembered coming home after the war ended, finding her mother, and not being able to communicate with her because she only spoke German and her mother only spoke Czech.

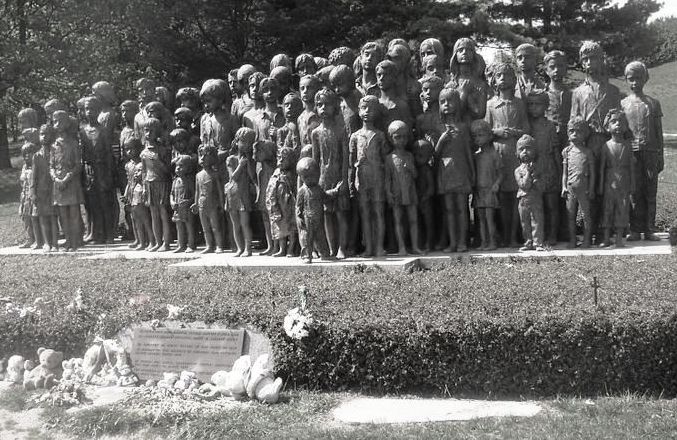

In one monument, 82 life-size bronze children stand grouped together on the grass. On the plaque in front of the sculpture, it is written, “82 children of Lidice gassed by the Nazis in 1942. In memory of the millions of children who perished in the Second World War.” Around the sculptures visitors have left mementos: flowers, candles and small toys to honor the children.

After the war, people rebuilt. The new town of Lidice was built 300 meters from the original site. Several towns across the world also took on the name Lidice to honor the memory of the village, including towns in Mexico, Venezuela and Brazil. It is always surprising–even after great tragedy, life somehow manages to go on.

I visited this town on a class field trip. It is very hard to visit these places and to write about death like this, the death of innocent people, the death of children. It is hard to read about it also. However, I believe skipping over the story of this village would be an insult to these people’s memory. This history is not easy–not much of history is–but it is important to remember these people and it is important to continue to educate on how massacres like this ever became possible, so that we do not forget.

It is important to tell the stories of how and why these people died. In an age where neo-Nazis are alive and well, it is imperative to look to the past for guidance, to remind ourselves of from what we have come and why we must never go back.

Information for this story was gathered from www.lidice-memorial.cz, www.holocaustresearchproject.org, and www.history.com.