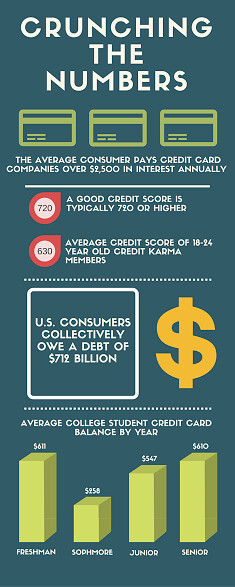

U.S. consumers collectively owe a debt of $712 billion, with the average credit card balance-holding household over $15,000 in overall debt. The millennial generation has taken on much more debt – averaging $5,000 more – and at higher interest rates than the generation before them. However, due to federal regulation changes, as well as an increasingly debt conscience generation, the rates of students holding credit cards, and their owed balances, are declining.

What is credit, why do you need it and how do you get it?

Having credit is almost a necessity in today’s world, and having good credit can actually help lower a person’s insurance rates, increase their employment opportunities, and ease the process of finding a house or apartment to rent. But what exactly is credit and how is your credit score decided?

Credit is a person’s reputation as a borrower, and is therefore used by lenders to determine how likely a person is to repay their loans. A credit score is a number between 301 and 850 generated by a computer program that reads through a credit report. A good credit score is generally considered to be 720 or higher, but standards vary among lenders. According to Credit Karma, the average score of its 18 to 24-year-old members is 630.

Credit also determines the interest rate with which someone can borrow money. Over the course of a lifetime this can mean some serious cash.

If two people – one with a good credit score and one with a bad credit score – bought houses for $300,000, each with a 30-year fixed mortgage, the person with good credit could pay a total of $90,000 less for that house over the loan’s lifespan.

The simplest and most common way to build credit is by getting a credit card. However, this can lead to a good or bad credit history. The best advice for someone looking to build good credit is to use their credit card for routine purchases such as gas and groceries, and then pay off the balance every month.

This is easier said than done.

Recent trends

As of November 2015, just over 38 percent of all U.S. households carried some sort of credit card debt. It is easy to attribute credit card debt to irresponsible spending, but it is not that simple. Reports have pointed to the fact that, in recent years, the cost of living has outpaced income growth.

Since 2003 the cost of living has increased by 29 percent. Meanwhile, income has grown by only 26 percent. A three percent difference may not seem significant, but it can be. Those most affected include individuals working jobs with stagnant wages, people living in high-cost cities, students, and people who suffer from health problems.

In 2009, during the height of the recession, household debt had grown 42 percent faster than income since 2003. This growth has fallen back down, however in 2015 the difference was still a concerning 15 percent.

Households with the lowest net worth hold the highest average amount of credit card debt at $10,308. This debt cycle can be vicious. Credit card debt is one of the most expensive types of debt, and costs consumers an average of $2,630 per year in interest.

Because of the often-false assumption that credit card debt is the result of irresponsible spending, there is stigma surrounding this particular type of debt. This stigma has led to a $415 billion difference in reporting between consumers and lenders. In a 2013 poll, 85 percent of respondents said that they were unlikely or somewhat unlikely to discuss credit card debt with a stranger, making the topic more taboo than religion, politics, salary and love life details.

While the national average for household credit card debt saw a small decline between 2010 and 2013, the amount has been slowly but steadily increasing over the past two years. For a variety of reasons, student credit card habits have been shifting in the opposite direction.

Student cardholders

At $925, the average credit card balance for undergraduate students in 2013 (zero dollar balances excluded) was less than a third of what it was in 2008. Reports indicate that 78 percent of undergraduate students using a credit card have a balance between zero and $500. In 2010, the average monthly payment was $168. In 2013, it had dropped down to $6. And the overall number of college undergraduates who hold a credit card dropped from 42 percent in 2010 to 30 percent three years later.

These trends can be explained in large part by the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009. The CARD Act was a consumer protection bill that established “fair and transparent practices relating to the extension of credit.” The CARD Act reduced hidden fees and regulated card approval criteria for those under 21. A study conducted by the University of Chicago determined that the CARD Act is saving consumers $20.8 billion a year in reduced fees, with especially high savings for those with poor credit.

Along with these national effects, the CARD Act had a dramatic influence on the credit card habits of college students. Previously, any 18-year-old could sign up for a credit card (guaranteed to have a high APR rate), and they often did after being wooed with free handouts such as t-shirts, pens, frisbees and tote bags. After the CARD Act, these tangible enticements were largely banned and anyone under the age of 21 would have to either have proof of income or a co-signer.

Millenials have been described as an increasingly debt conscious generation, which is another possible reason for the decrease in college students with credit cards. As the percent of students taking out loans, and the amount of these loans, has steadily increased, anxiety about finances has also gone up. While student loan payments leave millennials strapped for cash, creating more potential for both the necessity and abuse of credit cards, many current college students are eager to avoid piling on to this debt.

In a survey sent out to New College students, 80 percent of those with credit cards reported that they paid it off every month. Of those that had a recurring remaining balance, just under half said that they had used some or all of their refund check to pay it down.

Thesis student Bo Buford does not have a credit card yet but would like to get one to start building credit and to have in case of emergencies.

“Because refund checks took so long to come in, it would have been nice to have a credit card to cover some of the expenses in the meantime like groceries,” Buford said.

Second-year Rachael Murphy got her first credit card because of emergency dental expenses.

“It’s called CareCredit and it’s mainly for dental and medical stuff,” said Murphy, who is still paying off her balance. “It’s like a loan but on a credit card for a specific thing.”

Transfer student Ezra Katz is also still paying off a credit card balance.

“I was 19 [when I got my first credit card] and I wanted to start building credit,” Katz said. “For the first year and a half I was able to keep it paid off every month…it only really became a necessity for me in the past year.”

Though the CARD Act implemented many more regulations, credit card companies still have their tricks.

“Something that was interesting about mine is that they will raise the limit when I qualify for a limit raise without consulting me about it,” Katz said. “I used to only be able to incur about $900 of debt and now I’m up to like $1,300 and it’s not really something I would have chosen if given the option.”

Information for this article was taken from NYTimes.com, nerdwallet.com, cardhub.com, and dailyfinance.com.