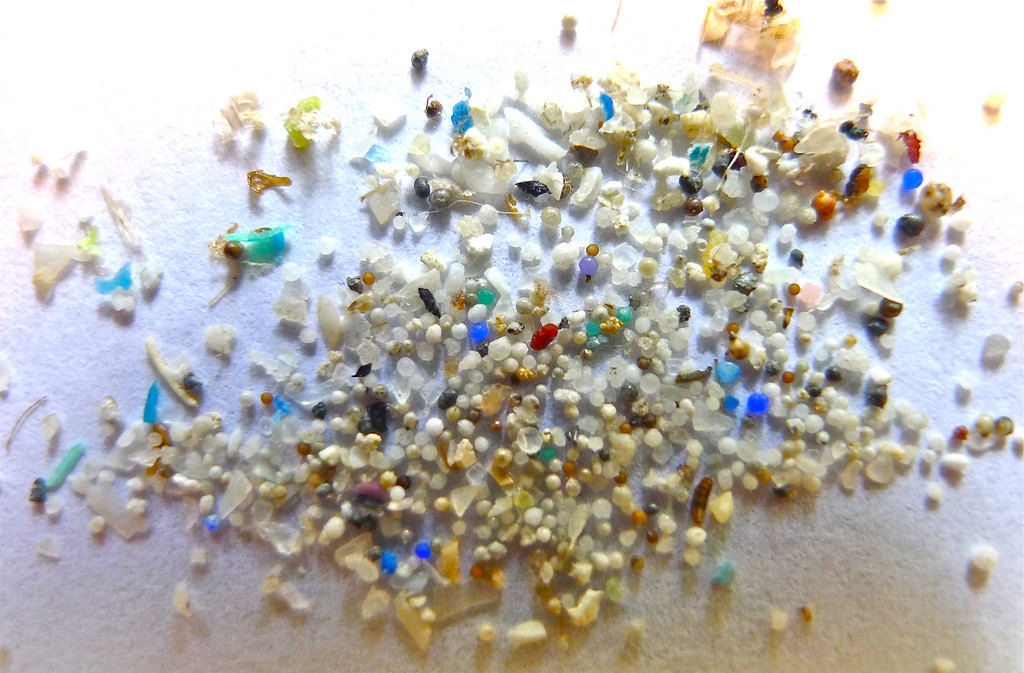

Microplastics are particles of plastic, usually smaller than a quarter inch. The water-treatment facilities cannot filter them out, and they go into the ocean. Dozens of products list microplastic as an ingredient. “Each time you wash your face or brush your teeth, you just may be adding microscopic bits of plastic into the aquatic environment,” the Florida Microplastic Awareness Project said.

Professor of Biology and Marine Science Sandra Gilchrist and Professor David Hastings, a marine geochemist at Eckerd College, have each received grants to look at the effects of microplastic. Gilchrist is studying the presence of microplastics in the Sarasota Bay and Hastings is studying the Tampa Bay.

Hasting’s annual phytoplankton study with his students inspired his study. While examining the phytoplankton under a microscope, Hastings found something he didn’t expect.

“I saw lots of filaments, threads, chunks and flakes of plastic,” Hastings said.

These particles also reside in different layers of sediment on the shore. Microplastic is present in all tap water and is more concentrated in single-use bottled water. Plastic becomes brittle overtime and breaks down into smaller pieces, but it is not biodegradable. It will stay in the ocean for thousands of years, and the amount of microplastic increases daily.

“Microplastics are very detrimental in the marine environment,” Gilchrist said.

The two main environmental concerns that Gilchrist and Hastings are studying are the effects of microplastic on filter feeders and the persistent organic pollutants (POP) that live on the surface of microplastics. Filter feeders, such as oysters, mussels, crabs and sponges, filter ocean water as their food source. When they filter the water, pieces of microplastic can get stuck in their gut. This tricks them into thinking they are full, and eventually the organism starves to death because they cannot digest the plastic.

Persistent organic pollutants (POP) may live on the surface of the microplastic. According to Hastings, these toxic compounds prefer to stick to the surface of plastic rather than sand or shells. One of these compounds is polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH). PAH comes from coal, tar and organic matter that has not combusted completely. The other compound is polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB). It was first used in coolants and carbonless copy paper. However, the production of PCB, considered carcinogenic to humans, was banned in the U.S. in 1978. PCBs are still produced today even though some countries have banned them. With her grant, Gilchrist is looking closer into these microbiomes to see if they merely reside on the plastic, or if they actually consume it.

There is little research on the effects of microplastic on human health. Hastings says he is not as concerned about microplastic consumption in humans because the most affected are filter feeders. The amount of POPs on each piece of microplastic is small enough that it will most likely just pass through the human digestive system. However, there have been a few speculations – which require more studies – that the consumption of microplastic may lead to infertility and issues with digesting food. For now, it is a mystery, but humans are consuming microplastic constantly.

“Microplastics are in beer, salt, drinking water,” Hastings said. “It’s almost everywhere.”

While the effects of microplastics on humans are unknown, the effect of humans on microplastics are well-documented. Synthetic fibers in athletic wear and sports jackets release thousands of microplastic filaments each time they are washed. These filaments are drained out of the washer and into the ocean.

In 2016, Patagonia, an outdoor clothing gear company, conducted a study that observed the amount of microfibers in the water of a washing machine after washing one of their synthetic fabric jackets. They are now partnered with North Carolina State University (NCSU) to develop ways to prevent these large contributions of microplastic from entering into marine ecosystems. Their suggestions for consumers is to wash clothing items made of synthetic material less and purchase high-quality athletic wear because low-quality materials release more microfilaments per wash. They also recommend using a front-load washing machine versus a top-load and putting synthetic clothing in filter bags to prevent microfibers from going down the drain.

The Ringling College of Art and Design is holding an exhibit entitled “Microplastics” from Nov. 13 to Dec. 14. It will be in the Willis Smith Gallery in the Larry R. Thompson Academic Center. Information for this article was gathered from patagonia.com and sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu.