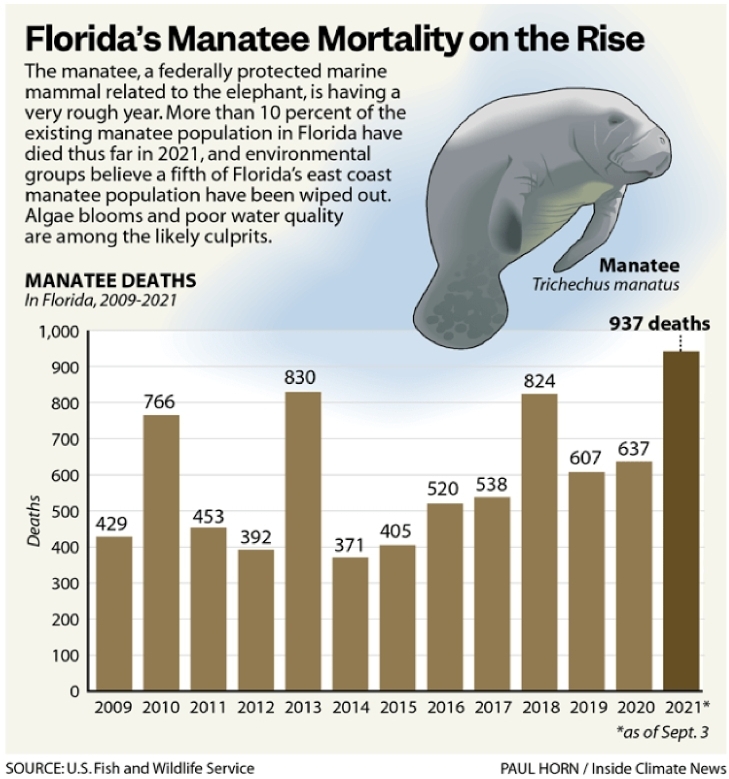

Manatees are a Florida hallmark, both to its identity and to its ecosystems. However, despite their population increasing over the last 50 years, 2021 has brought record levels of manatee deaths, with no sign of improvement. This Unusual Mortality Event (UME) has reignited criticism of a controversial 2017 decision to downlist the West Indian Manatee from endangered to threatened and intensified efforts to mitigate manatee mortality and stabilize the population.

In the 1970s, there were just a few hundred West Indian manatees in Florida. The manatee’s importance, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), lies primarily in their heavy consumption of sea grass, which keeps the grass short, helping to “maintain the health of the sea grass beds.” Additionally, because manatees have no natural predators, they are a great indicator of ecosystem health.

Beginning with the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and the Florida Manatee Sanctuary Act of 1978, manatees have been provided with legal protection, including making it illegal to feed, harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, annoy or molest manatees, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). Additionally, the state provides “regulatory speed zones to protect the manatee and its habitat.”

With these protections and the hard work of countless environmentalists, activists and rescuers, manatees have seen dramatic increases in their population over the last fifty years.

“Today, the range-wide population is estimated to be at least 13,000 manatees, with more than 6,500 in the southeastern United States and Puerto Rico,” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). “When aerial surveys began in 1991, there were an estimated 1,267 manatees in Florida. Today there are more than 6,300 in Florida, representing a significant increase over the past 25 years.”

However, when the USFWS used this reasoning to “effectively declare the manatee on the way toward recovery and downlisted the animal from endangered to threatened,” it “generated widespread opposition,” according to WLRN, a Miami news outlet. The reasons for this opposition among experts were that it was premature and “neglected scientifically documented warning signs at the time that manatees were in trouble.” Unfortunately, the experts have been proven right since then, and manatees have been dying at record rates.

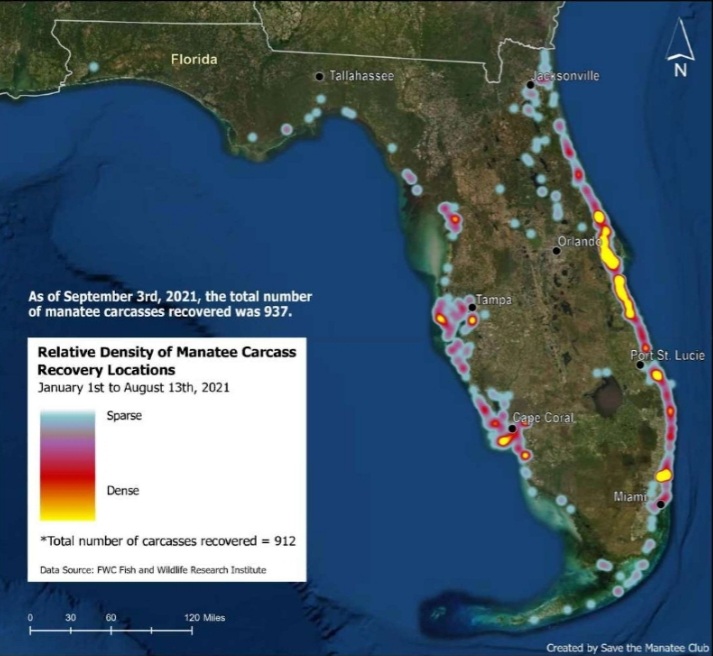

“The combination of unprecedented mortality from starvation and serial record-breaking watercraft mortality has led to the recent loss of 20% of the East Coast manatee population in just a six-month period,” said aquatic biologist and manatee expert Patrick Rose at Save the Manatee Club.

“For the past several years, ongoing nutrient pollution associated, for instance, with fertilizers, produced mainly from natural gas and septic tanks have triggered harmful algae blooms,” according to WLRN. These algae blooms severely affect the Indian River Lagoon, one of the primary habitats of the Florida manatee, and “can cloud the lagoon’s historically crystal-clear water, preventing sunlight from reaching the seagrass undulating beneath the surface. Since 2009, at least 58 percent of the seagrass in the northern Indian River Lagoon has been lost. In the Banana River, part of the northern lagoon, at least 96 percent of the seagrass is gone.”

Though deaths are concentrated in the Indian River Lagoon, “the more recent mortality is shifting to a higher incidence on the west coast,” according to Rose. Hometown Red Tide is likely to blame.

The USFWS defends itself by saying that, despite the delisting, no protections were removed. Rose said, however, that “not only did the downlisting not meet Endangered Species Act requirements, which among other things demand an assurance the animal’s habitat is secure and will remain that way for the foreseeable future, but it also sent the message the manatee was OK when it was not, which can affect policy decisions and public attitudes toward the animal,” according to WLRN. “The Save the Manatee Club along with the Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife together have filed a notice of intent to sue USFWS over the manatee’s current plight.”

“There really is no causal relationship between its listed status and what has unfortunately occurred in the Indian River Lagoon,” a USFWS spokesperson Chuck Underwood countered.

In addition to the lawsuit, Rep. Buchanan, Vern [R-FL-16] has introduced a bill to reclassify the manatee as endangered, which, according to Assistant Professor of Biology and Marine Science Athena Rycyk, “is unusual—the typical path is submitting a petition to the Fish & Wildlife Service (a long process).”

The vast number of manatee deaths this year has been labeled an UME. Rycyk is offering a course in the spring, Analysis of Florida Manatee Mortality Events, related to the manatee UME.

The UME “now has prompted an urgent federal and state effort aimed at bracing for potentially more deaths this coming winter, as the Indian River Lagoon’s water quality problems and seagrass losses will not be resolved anytime soon,” according to WLRN.

Additionally, with colder weather soon to come, another wave of deaths in the manatee population is likely. Furthermore, because so many manatee deaths are the result of starvation resulting from a paucity of sea grass, the strain on the only four rehabilitation centers in Florida—SeaWorld, TampaZoo, Jacksonville Zoo and the Miami Seaquarium—is especially burdensome because starvation recovery takes six to eight months, contrasted with red tide recovery which takes just two to three weeks, according to WLRN. There is a worry that this could lead to a lack of space for manatees needing rehabilitation.

The unprecedented die-off is alarming not just for manatees, but also for the health of Florida’s coastal and water ecosystems as a whole.

“The cold hard fact is: Florida is at a water quality and climate crossroads, and manatees are our canary in the coal mine,” Florida director of environmental group Ocean Conservancy J.P. Brooker said.

While there is an encouraging amount of funding being poured into manatee recovery, detailed by ABC7, manatee deaths are likely to continue without a concerted effort to improve the quality of Florida’s water. As of Oct. 29, this number totals 988 manatee deaths.