Emmanuel Macron’s victory in the French presidential election marked the end of the most contentious and polarizing election season in the history of the Fifth Republic. Macron and his independent centrist party En Marche! defeated Marine Le Pen and the far-right Front National (FN) on Sunday May 7, with Macron winning 66.1 percent of the vote.

Voter turnout was the lowest France has seen since 1969 and almost 9 percent of voters filed blank ballots, an indication of voters’ widespread dissatisfaction with the candidates – and with the French political system at large. Both final candidates were from non-establishment parties, marking the first time in modern French history that neither the dominant leftist party, the Parti socialiste (PS), or the dominant right-wing party, Les Républicains (LR), were represented in the second round of voting.

“I think that both Trump’s victory and Brexit were sort of a wake up call to a lot of European voters that ‘Yes, you might be angry with the status quo, but a protest vote or a vote against the system can have negative consequences that you might not like,’” Professor of History David Harvey said. “Both [Trump’s victory and Brexit] may have encouraged more people to take a second look, even if they weren’t necessarily wild about the choices offered to them, and to get engaged and make a responsible choice.”

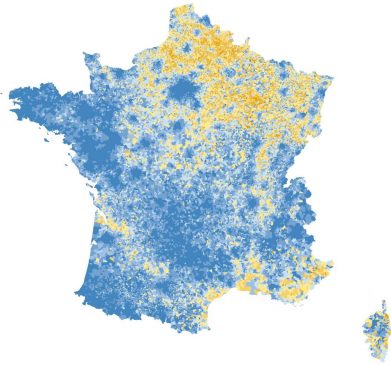

Macron founded his En Marche! movement in April 2016 and Le Pen took over her father’s far-right – and arguably bordering on neo-fascist – Front National party in 2011. Both parties departed from the traditional center-left and center-right orientation of the major political parties in contemporary France, each claiming to offer new solutions to the problems of economic stagnation, terrorism and the perception of France’s declining influence on the world stage. While Macron emphasized his hopes for a new future for France, a future based on increased economic competitiveness and further integration with Europe and the world, Le Pen focused on the fears of the French people. She did especially well in areas that suffered from high levels of poverty and unemployment caused by deindustrialization and those that have faced a perceived increase in the presence of immigrants and refugees.

“Macron had never run for office before,” Harvey said. “He’s a banker who had been the economics minister under the socialist government of François Hollande, but he wasn’t a socialist party member. He founded his own political movement and ran as his own sort of candidate – and he also marked a bit of a break from the French general political landscape. And this is sort of another ‘Americanization’ thing, but I think he would fit very well in the mainstream of the American Democratic party in that he ran as a liberal on social issues but more moderate to conservative on economic issues. He’s a centrist even though most people would see him – at least since he ran against a far-right candidate – as sort of the more progressive option.”

Although support for Le Pen was lower than the polls predicted, the FN received more votes than ever before in its history. When Le Pen ran in the 2012 Presidential election she came in third in the first round, winning 17.9 percent of the vote. The results of the 2017 election reveal that 35.4 percent of French voters voted in support of the FN and in favor of a candidate who advocated for the removal of France from the European Union (EU) – a huge blow to European integration efforts and the democratic legitimacy of the EU in France.

“I think it’s a very good thing that she [Le Pen] didn’t win, but she won 34 percent in a national election which is considerably more than any candidate from the far-right has won in France in its modern history,” Harvey said. “That is significant. Moreover, I think Macron has the right ideas and the right program, but it’s not a given that he’ll be successful and a lot of the factors that led to the growth and support for the Front National will still be there: the economic insecurity of a lot of people, fears about loss of national autonomy through globalization and the EU, and particularly, the backlash against multiculturalism and the diverse society that France has become.”

France’s role as a founding member of the EU – and the second most powerful and influential nation currently in the EU – makes the far-right’s call for the removal of France from the EU equitable to a mandate for the dissolution of the EU as a whole. Macron’s support for the EU and for France’s continued participation in European integration led to his endorsement by of a number of European leaders, including Angela Merkel, the current Chancellor of Germany. Macron also received a public endorsement from previous United States President Barack Obama, who posted a video on Twitter that ends with “En Marche! Vive la France!” Obama has long garnered support from the French people and remains very popular in France, while Trump, who has spoken favorably of Le Pen, remains extremely unpopular in France, even among members of the far-right.

“What is interesting is that Brexit and Trump and various other elections have been seen as – I think correctly – as sort of a populist backlash against globalization and technocracy and Macron is a candidate who sort of symbolizes both globalization and technocracy,” Harvey said. “There were so many things wrapped up in the election it’s hard to take it as a mandate for one particular thing, but I remember I watched news footage of Macron’s victory rally the Sunday night after the election and a lot of the people there were waving both French national and European Union flags. I think Macron managed to tap into a sense that the EU is still relevant and that the EU is the most effective vehicle for France to defend its interests and play a role both on the European and the world stage.”

Macron’s platform focused on promoting globalization and European integration through maintaining the EU while also emphasizing the need for reform at the European-level, particularly in terms of increased efficiency and a higher level of democratic accountability – critiques that the EU has faced continuously since its conception.

“I think he’s going to focus on the Franco-German partnership and close relations with Angela Merkel’s government and trying to make the EU work more effectively,” Harvey said. “Whereas Le Pen had talked about pulling France out of the EU and out of NATO, Macron will be looking to work through multinational organizations to make them work better and to secure benefits for France. The Franco-German partnership has been at the core of European integration from the very beginning, and I think that if Le Pen had won that would have been damaged – perhaps beyond repair.

“With Macron winning – and certainly if Merkel and her coalition are re-elected, or even if there is a new SPD coalition – I think that partnership will continue. They’ll have a lot of obstacles to deal with but that would make me at least cautiously optimistic that the EU can survive and can adapt themselves to these new realities. Now whether they can solve the underlying problems – that’s a much bigger question.”

Information gathered from nytimes.com, vox.com and en-marche.fr