All photos courtesy of Allan Mestel

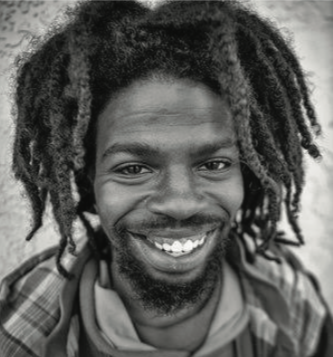

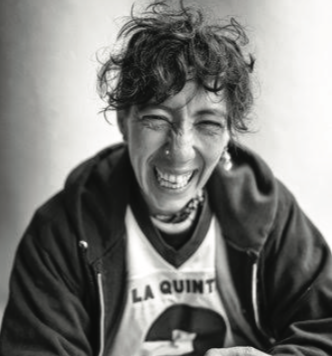

A diverse array of greyscaled eyes cover the walls of the “Homelessness in Focus” gallery. Some show playful joy, a few appear guarded and many express a sense of suffering. Above all, however, the eyes in focus exude strength. A spirit of human resilience can be felt from each photograph. Photographer Allan Mestel’s mission to capture the faces of the homeless is a way of humanizing the people so often ostracized from human connection.

The gallery is being shown at the Lexow Wing of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Sarasota from Sept. 15 to Oct. 17.

Mestel is a commercial photographer with a dedication to street portraiture. “Homelessness in Focus” is a project pursued out of passion for understanding and representing the faces of individuals who have been ignored and outcasted because of their economic hardships.

His interest in specializing on people living on the streets began 15 years ago, while filming for United Way in Toronto. He was inspired by the weeks he spent working at shelters, capturing the work United Way had done and learning about the lives of the homeless.

“I became fascinated by the people I met, and how different they were from what society expects; their backgrounds, where they came from, what their personalities were like. I met gentle, humble, sweet-natured people,” Mestel said.

Mestel emphasized his shooting protocol, as he values the close, physical proximity in the atmosphere of his work.

“I never shoot from a distance, because visually it looks like spying,” Mestel said. “I always shoot at eye level or below, because what I want to give people is an encounter experience. The sense of immediacy and proximity is essential, that way you are forced to look into the face that you would shy away from in life, that you would ignore, that you would avert your eyes. With the images, I want to draw people into the faces, instead of away.”

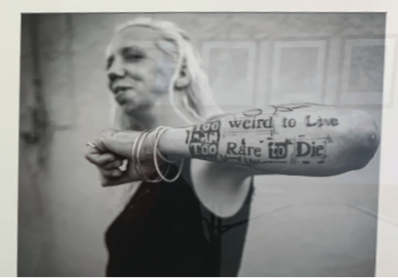

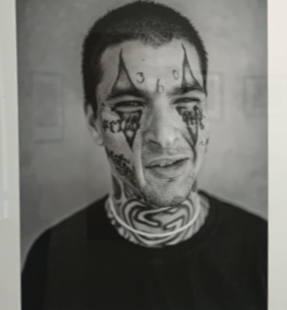

Two photos in the gallery stand out, as the images break from protocol. The focus shifts away from eye level to the tattoos of phrases and images that decorate their bodies. Menstel was particularly fascinated by the tattoos; the art that becomes eternally apart of the skin. For some living on the street, the skin on their backs has been their only permanent possessions. The designs are an insight into the past of individuals.

“I met Johnny at the Salvation Army,” Menstel said. “He was coming out of jail and looking for a spot in a rehab center. One of the drug counselors close to him told me the history behind the tattoos. He had went to jail at a young age and got his tattoos just to intimidate people; they were a way to defend himself, a sort of armor to protect him from the older, violent prisoners.”

Johnny’s tattoos cover his face, arms and neck fully; the image is powerfully focused on his eyes and expression beneath the ink.

In order to capture his subjects, he remains aware of his own presence during a shoot.

“I keep my input of energy in check, because I don’t want to see myself reflected in the images,” Menstel said. “I only inject enough energy into the interaction for them to give me an authentic, emotional reaction.”

This idea is evident by the diversity of the galley, as each subject has a unique expression and personal style distinct to them.

“It’s me trying to provide a mechanism for people to connect emotionally with an individual they would almost never approach in reality,” Menstel said.

He views art as a means of raising awareness of the humanity of those in poverty, and the gallery beautifully portrays the spectrum of Bradenton’s homeless community.