photo courtesy of Kaley Soud/Catalyst

First-year Alan Sachnowski holds a red rat snake caught outside of Second Court.

During the first week of school, a girl sat silently one serene summer morning, reading Catullus to the sound of birds chirping and a Pileated Woodpecker pecking impatiently at the tree overhead when, not so suddenly, an Apone ferox slowly trudges across the path before her eventually resting beside her. This girl observed placidly the sizeable Florida soft shell turtle next to her while it looked back at her with eyes equally placid for a good while before the ferox returned to trudging and the girl to reading.

Reading Latin with woodpeckers and turtles, it takes the girl by surprise when, not even 50 feet away, a rotten old pine tree collapses across the same path the turtle just took. She looks surprised, the turtle tucks momentarily back into his shell in apprehension and the woodpecker flies away perturbed — all of their mornings having been disturbed by this sudden occurrence.

The girl then, being of a particularly exploratory nature, ventured over to investigate this obviously rotten fallen giant only to see life teeming within. Just as her life had been touched this morning by the local fauna, so it seemed had this tree’s, which was riddled with insect eggs, squirrel nests, woodpecker holes and a troubled frog who quickly hopped away to find himself a new home.

As New College is in between the cities of Bradenton and Sarasota and across the street from an airport, wildlife is not something that one might immediately associate with the campus. But with the Myakka River right down the road and the Bay at its back, the New College campus actually teems with life other than stressed students and knowledgeable faculty.

photo courtesy of jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu

photo courtesy of jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu

Terrestrial wanderers

Life on the ground abounds. Besides a Florida soft shell lumbering along there have been multiple sightings of tipped over trash cans — implying the presence of certain quadrupedal masked bandits. One girl ran into a Elaphe guttata slithering swiftly outside of Second Court on the hunt for some vermin surely snacking on Novocollegian leftovers. An alum in the surrounding neighborhood is often spotted with a gray marsupial on his shoulder, after having rescued the creature from its mother who was killed on the road. Then of course there is always the invasive squirrel population of Sciurus carolinensis flitting about erratically with fluffy tails collecting foods and nesting materials in some sort of hurry. But the soft shells, raccoons, rat snakes, opossums and gray squirrels are really only a marginal fraction of the life that can be found.

Florida is a superb location for fauna: the consistently warm yearly climate encourages a great deal of life, particularly of the reptilian and amphibian variety. If one were to start looking in corners, around small bodies of waters and under logs and leaves he or she would be surprised to find just how much exists so closely to home.

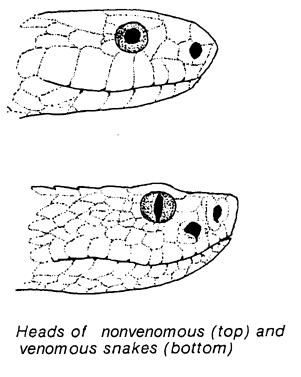

Snakes are one of the more commonly found animals and are also one of the most commonly misunderstood. There is the black racer, a particularly aggressive and common variety of snake, the yellow rat snake, which can reach lengths of more than six feet long and dispel a strong odor when threatened; and the red rat snake or corn snake, a particularly passive and non-aggressive species that come in all different colors and sizes. Perhaps the most difficult snake to deal with however is the the brown water snake, a threatening looking individual due to its similarities to the water moccasin — but actually its bite would result in nothing but mild irritation.

These snakes can be spotted regularly along with slider turtles and soft shells, Cuban tree frogs and the bumbling cane toads — both of which are among the most common amphibians in the area. They are also invasive species though, along with the Cuban anole, that are almost entirely choking out the native green tree frogs, green anoles, and eastern spade-foot toads.

Down by the bay

Every three years, an estuary report is released for the Tampa Bay region updating the public on the status of the bay on which they live. This year, the “State of the Bay Report” was released and featured positive information, such as a 64 percent reduction in nitrogen pollution since 1988, a 24 percent increase in seagrass coverage since 1950 and the return of bay scallops in 2008.

Right off the sea wall behind College Hall, when gazing at the sunset, there are mullet jumping left and right and stingray’s winds occasionally breaking the surface of the water. On closer investigation though, there is so much more. At the cost of rolling up one’s pants and hopping in just to see the response in the water is rewarding, little horseshoe crabs shuffle to the surface, small conchs majestically continue on their seemingly non-existent course, blue crabs and stone crabs dart away and the little hermit crabs quickly disappear into their homes.

For this type of investigating the explorer does have to watch his or her feet as there are stingrays lurking about — plus shells and horseshoe crabs aren’t too much fun to step on. But it is worthwhile just for the abundance of life you can invariably find.

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is one of Sarasota’s claims to fame, and one of the favorite on-campus activities is to take a dip in the illuminated waters that come in the fall. It is truly phenomenal to watch the water light up at the smallest of movements and seems quite inexplicable in its near intangibility.

Behind this phenomenon though, the truth is dinoflagellates. Dinoflagellates are tiny plants that live in the sea and emit a bright blue light at night in response to movement. They produce luminescence on a circadian rhythm — dependent on 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark. During the day, when not illuminated, the dinoflagellates appear as ellipse shaped cells,

pigmented red, indicating the presence of chlorophyll enabling photosynthesis to occur so they may harvest light from the sun and the cycle may be repeated.

Dinoflagellates use bioluminescence as a type of defense mechanism. When the cell is disturbed by a predator, it will give a light flash lasting 0.1 to 0.5 seconds. The flash is meant to attract a secondary predator that will be more likely to attack the predator that is trying to consume the dinoflagellate. The light flash is meant to make the predator jump and worry about other predators attacking it, making the it less likely to prey on the dinoflagellate.

While it is an intense scientific process, it is immensely enjoyable to observe ones limbs light up with an almost magical presence, watching lighted water skirt down ones hand as he or she lifts it above the water.

Whether trekking on land or swimming in the sea, life abounds all over New College’s campus. As the girl who witnessed the falling of a tree and the presence of the rat snake, wildlife inspired one life to share with others. New College boasts the “independent research” of its students and from one “researcher” to another, there is so much to see.