Representatives from over 197 countries have gathered in Marrakech, Morocco for the twenty-second session Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), otherwise known as COP22. The meeting is a follow-up to COP21 in Paris and will take place from Nov. 7 to Nov. 18.

“The politically difficult step was Paris,” Robert Stavins, an environmental economist at Harvard University, told the Wall Street Journal. “The technically difficult steps now remain.”

In the Paris Agreement countries aimed to tackle climate change by pledging to keep the global temperature rise this century “well below” 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to further limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The agreement also called for a peak in greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible and hoped to achieve a balance between sources and sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century. It was agreed that countries would put forth plans as to how they were going to cut emissions and progress would be reviewed every five years. Lastly, it was determined that $100 billion a year in climate finance for developing countries would be gathered and given by 2020, with a commitment to further finance in the future. The money is meant to come from developed nations.

Show me the money

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is arguably one of the most important aspects to come out of the Paris talks. The Fund plans to respond to climate change by investing into low-emission and climate-resilient development. It aims to “limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions in developing countries, and to help adapt vulnerable societies to the unavoidable impacts of climate change,” according to the GCF website.

So far, 57 developing countries are receiving readiness support from the GCF, with $16 million in readiness grants already approved. Of these countries, 37 are Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and African States. The GCF Board hopes to approve $2.5 billion in funding proposals in 2016.

However, Piyush Goyal, India’s minister of power, told the Wall Street Journal several days before the Marrakech conference began that little of the GCF money developed countries have promised to funnel into developing world green energy projects has begun to flow. He said that financing to upgrade the dirtiest outdated technologies, such as the majority of India’s coal plants, has dried up.

“Everybody believes in principle there should be a 100 billion dollars that should come from industrialized countries to help developing countries transition but nobody agrees what type of money we’re talking about and who’s responsible for what specific amount,” said Professor of Political Science Frank Alcock. “I cannot imagine right now under Republican leadership with Donald Trump as president that a penny will flow in terms of official government money into this Green Climate Fund.”

Following up Paris

The Paris Agreement entered into force on Nov. 4 after it cleared the final threshold of having at least 55 signatories representing more than 55 percent of global emissions ratify it, including the United States, China, the European Union and India. The relatively quick ratification will be beneficial in furthering action in Marrakech.

The talks in Marrakech will face several obstacles, including hashing out details of the Green Climate Fund, ratcheting up plans to achieve the 2 degree goal and determining the logistics of how countries will be held accountable to the plans they set for themselves in Paris, a difficult dilemma. It was agreed on in Paris that the requirements each country set for themselves would not be mandatory; when the United Nations (UN) tried a mandatory approach many countries that failed to meet their requirements quit.

Urgency (and disappointing election results) in Marrakech

On Nov. 3, a UN review of national pledges from governments that have ratified the accord to cut carbon emissions said they fall short of the levels needed to keep the rise in global temperatures under 2 degrees Celsius. The report found that the pledges would see the world on track for a rise in temperatures by the end of this century of between 2.9 and 3.4 degrees Celsius.

Environmental groups and other experts have urged governments to step up their plans for limiting the rise of global temperatures and to retain the sense of urgency felt in Paris last year going into Marrakech.

In her opening address on the first day of COP22 UNFCCC Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa said that the early entry into force of the Paris Agreement, while a cause for celebration, is also “a timely reminder of the high expectations that are now placed upon governments.” Espinosa said that the peaking of global emissions is urgent, as is attaining more climate-resilient societies.

Espinosa underlined several key areas in which work needs to be taken forward. She stated that finance must continue to allow developing countries continue to green their economies and build resilience, and that fully engaging non-party stakeholders including businesses are central to the global climate action agenda.

“I don’t think that the agreement is enough to prevent that [temperature rise more than 2 degrees Celsius] from happening but it’s not a bad thing, like it’s a start,” Vice President of Green Affairs (VPGA) Orion Morton said. “I don’t think that as much as they purport will change because of it but that isn’t to say that there won’t be real tangible change that comes as a result.”

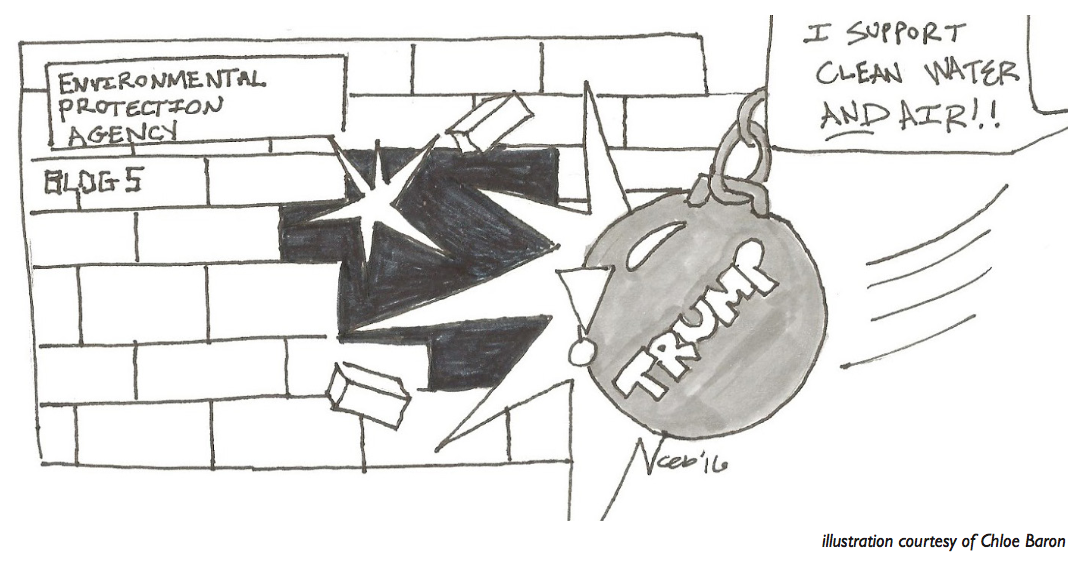

Representatives in Marrakech worry how the results of the United States election will play out in regards to the agreement and climate change. President-elect Donald Trump has called climate change a “Chinese hoax” and has vowed to back out of the Paris deal. He has also promised to withdraw the Obama administration’s biggest climate regulations and cut off U.S. aid to the GCF.

While Trump wouldn’t be able to cancel the deal unilaterally, he could begin the process of withdrawing the U.S. from it, which would have a major effect on the effectiveness and success of the Marrakech conference, and take other steps that could freeze U.S. climate policies, according to the Wall Street Journal. The reality of a Republican controlled Congress is also a scary thought for many climate scientists.

At the Marrakech conference different days are dedicated to different topics. So far they have covered topics including cities at the center of climate change and water resilience in Africa. Before the conference wraps up on Nov. 18 much work needs to be done if real action is to been seen.

Information from this article was gathered from wsj.com, bbc.com, greenclimate.fund, cop22-morocco.com.