In the morning of Feb. 24, 2022, (Eastern European Standard Time) President of Russia Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation in Ukraine,” and just after explosions were reported in major cities across Ukraine. Russian troops, which had been amassed in areas surrounding Ukraine, near the border with Russia, Belarus, Crimea and even Transnistria, invaded soon after. This buildup of troops first made headlines last spring, with concurrent estimated numbers over 100,000, and current estimates as high as 190,000. Russia’s excuse for this development was inconsistent, though usually involved invocations of training exercises or alleged buildups by Ukraine. Moscow always denied there would be an invasion until it happened, and accused Washington of “hysteria.” However, the buildup was not kept a secret, and, on Apr. 20 2021, the New York Times wrote, “the high visibility has cost Russia any element of surprise, leading analysts to minimize but not rule out the possibility of an actual attack. More likely, they say, the buildup is intended as a warning to the West not to take Russia for granted.”

Concerns, however, continued to rise. In late Nov. 2021, ABC News published an article saying, “Of course no one knows if Russian President Vladimir Putin is really planning an attack. Russian experts are fiercely divided over the Kremlin’s intentions: Is the country bluffing or flexing its muscles to intimidate Ukraine and the U.S. into concessions? Or is it preparing a real invasion?”

This division among experts lasted until at least the middle of February, 2022. However, U.S. intelligence consistently led the pack in its confidence in a Russian invasion, with Biden predicting it to be more likely than not in late January.

At the end of January, there were reports of perishable materials such as blood and medical supplies being transported to these troops, which helped to confirm doubts about Russia’s excuse that said troops were merely participating in training, where such materials would not be used.

As the situation heated up to unprecedented levels, many foreign officials in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, began to evacuate or move to Lviv, closer to the border with Poland.

On Feb. 15, however, Russia confirmed a partial withdrawal of troops from the Ukraine border, yet “Western officials said there were no immediate signs of a Russian drawdown. ‘So far we have not seen any de-escalation on the ground from the Russian side. Over the last weeks and days we have seen the opposite,’” according to the Guardian.

However, the same day, the Guardian reported “Kyiv starts to breathe a little easier as Russian troops pull back.”

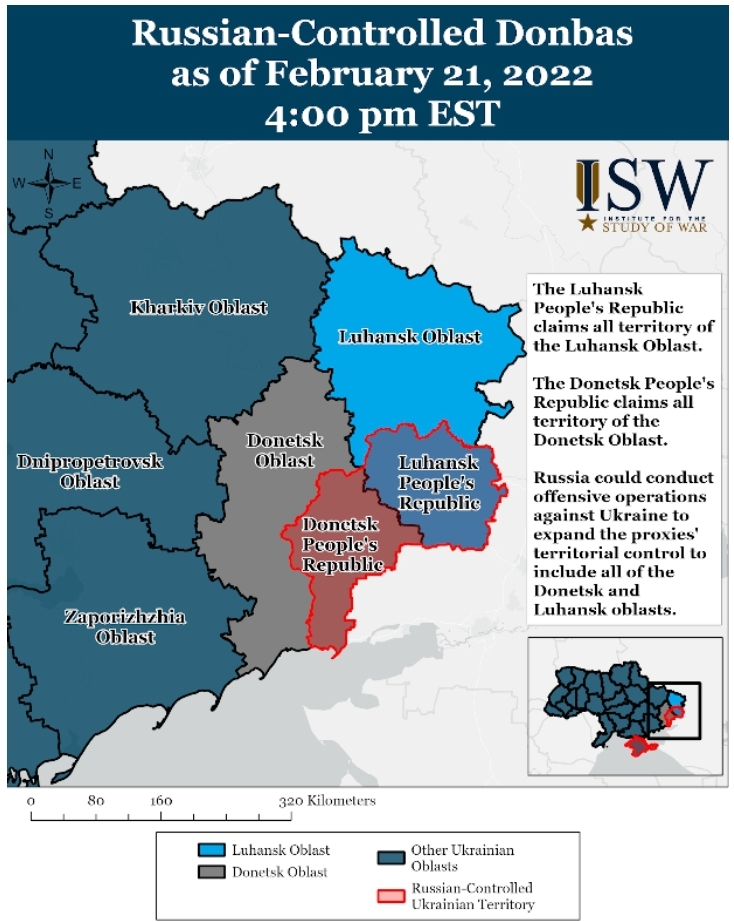

All signs began to point to invasion soon after, especially when, in a “fiery address,” Putin recognized the Ukrainian separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk as “independent,” an act which Putin quickly followed by instructing “the Defense Ministry to send troops into the territories for what the Kremlin called ‘the function of peacekeeping,’” according to Deutsche Welle.

U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield described the act as “part of its attempt to create a pretext for a further invasion of Ukraine,” according to Reuters.

Expert Opinions Prior to Invasion

Up to this point, those who thought Putin was going to invade rarely agreed on what that meant or how it would look, with various degrees of invasion discussed as possibilities, few suspecting full-scale invasion, occupation and incorporation. The “relocation” of officials from Lviv to Poland, as well as reported discussion of evacuation plans of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy with U.S. officials on Feb. 25 may have suggested increasing confidence in a larger scale Russian invasion.

In an interview published on Feb. 16, 2022, University of Rochester’s Russia expert Randall Stone said, “Russia has the military capacity to defeat the Ukrainian army, mainly because Ukraine has no effective answer to the Russian air force. On the other hand, a long-term occupation of the whole country would be difficult… Yet that combat-ready force [of 175,000] is not sufficient to occupy a country the size of Ukraine and pacify it against active resistance. Russia would have to mobilize a lot more forces, and it would be a long, bloody conflict.”

“The cost of an invasion would be tremendous,” Stone continued. “It would pit Russia against the West in a way that it has not been since the Cold War. After this, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) would be more militarized and Russia would be less secure. And, ironically, an invasion would make it much more likely that what’s left of Ukraine eventually ends up becoming a member of NATO.”

“The economic sanctions that NATO allies have promised in response to an invasion would disrupt Russia’s trade, destabilize its banking system, cause the ruble to lose much of its value and drive down the standard of living of ordinary Russians,” Stone elaborated. “This doesn’t make sense as the endpoint of a strategy. It looks more like a fallback position—just like seizing Crimea was—to cover up a miscalculation. Putin calculated that if he bluffed, the West would fold. Now he is stuck with a bet that he cannot cover, and he has to decide whether to cut his losses or escalate.”

While many thought that the costs of invasion were simply too high, Stone’s proposed explanation of Putin’s (at the time hypothetical) decision to invade despite such costs as being the result of a failed bluff, as being miscalculated rather than calculated, makes sense of the senseless and has since been replicated by others.

Fears and the Future

Alternatively, Putin simply wants Ukraine more than he can stand. Casey Michel wrote, just before the invasion, “This is, after all, a president who has previously claimed that Ukraine ‘is not a country’ and that Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people—a single whole.’”

Continuing in his analysis of Putin, Michel says, “the Russian dictator has grown to see himself as not another middling, kleptocratic dictator, but as a figure of historic import, dedicated to restoring Russian greatness—and to unwinding the gains the West made when Russia was at its weakest following the Soviet collapse.”

Michel says that Ukraine is the first piece of a much greater ambition, to “rewrite Europe’s security order wholesale: to roll back the democratic, NATO-led gains of the past two decades, all to redound to Moscow’s benefit. All by launching what could become the greatest war Europe has seen in nearly a century, with all of the bloodshed and destruction attendant—none of which will be limited to Ukraine.”

These fears are not Michel’s alone. The heights of Putin’s egomania were mentioned by Director of the Center for Eurasian, Russian & East European Studies at Georgetown University Angela Stent in a lecture for the Sarasota World Affairs Council attended by a Catalyst reporter on Feb. 15, 2022.

“Putin is obsessed with Ukraine, feels it’s part of Russia…[and] he wants to be seen as the great Russian leader that regathered the lands…Ukraine is the most important piece of that,” Stent said.

In the same lecture, former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine Bill Taylor said he thought invasion was unlikely.

These fears are clearly widespread in other former USSR or Warsaw Pact member countries: “Russia’s attack on Ukraine sent shockwaves through the Baltic countries… along with Poland, also a NATO member, the small Baltic countries have been among the loudest advocates for powerful sanctions against Moscow and NATO reinforcements on the alliance’s eastern flank… Baltic government leaders in recent weeks have shuttled to European capitals, warning that the West must make Russian President Vladimir Putin pay for attacking Ukraine, or else his tanks will keep rolling toward other parts of the former Soviet empire,” according to an article published on Feb. 24, 2022 by the Associated Press (AP).

“‘The battle for Ukraine is a battle for Europe. If Putin is not stopped there, he will go further,’ Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis warned last week in a joint news conference with U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin,” the article continues.

These countries, despite nationalist governments which have been reluctant to accept refugees in the past, particularly Poland, have opened their doors to Ukrainian refugees, with Poland Interior Minister Mariusz Kaminski saying the country will accept “as many as there will be at our borders.”

Additionally, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said, “We’re prepared to take care of them, and we’ll be able to rise to the challenge quickly and efficiently.”

Moldova, Germany, and other nations have expressed similar sentiments. The disparity between the two approaches, both by governments and by the media’s coverage, has drawn significant criticism. There have also been reports of racist treatment of black Ukrainian refugees.

However, men aged 18-60, military age, are being stopped from leaving the country and conscripted into the military, a decree which will last as long as martial law remains in effect.

Status of the War

Quickly into the war, Ukrainians were using molotovs to resist Russian forces with far superior technology. Meanwhile, the President announced that “the Ukrainian authorities will hand weapons to all those willing to defend the country,” there were reports on Feb. 26 of “Russian frustration” with “viable” Ukrainian resistance.

On Feb. 24, in his invasion address, Putin declared, “No matter who tries to stand in our way or… create threats for our country and our people, they must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history,” and at another point mentioned that “Russia remains one of the most powerful nuclear states.” The same threat of mutual destruction that prevented nuclear war in the 20th Century remains today, but Russia is dancing worryingly close to NATO, especially if Putin has greater ambitions.

On Feb. 25, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova warned of “serious military-political consequences” if Finland or Sweden joined NATO, though these threats were “brushed off.” Still, Moscow is attempting to project strength and fear.

On Feb. 25, NATO activated the NRF, “a multinational force comprised of around 40,000 land, air, maritime and special operations personnel” to the “eastern part of the Alliance” to bolster defense. However, as Ukraine is not a member of NATO, though not for lack of want, NATO troops will not enter the country. Likewise, Biden made clear in an address on Feb. 24 that U.S. troops will not be sent to Ukraine. In the same address, he told Americans that gas prices are likely to rise, the result of sanctions on Russia.

In place of troops, Ukraine’s allies have taken up military aid and sanctions on Russia as tools of support. Some more distinctive sanctions include Germany freezing a pipeline which would double flow from Russia, possible restriction of Russian ships through the Bosphorous by Turkey, and, maybe most markedly, the exclusion of Russia from The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), announced on Feb. 26.

The goal of exclusion from SWIFT is to “promote soaring inflation in the Russian economy,” with the AP explaining that “the decline of the ruble would likely cause higher inflation, which would hurt everyday Russians and not just the Russian elites who were the targets of the original sanctions.”

Internal Status in Russia

Said everyday Russians engaged in widespread anti-war protests. The Washington Post published an article on Feb. 11, 2022, which said:

“Sending arms or deploying Russian troops into Ukraine is unpopular—and has only become more so as Russians tire of the war Moscow and its proxies have waged in eastern Ukraine since 2014. According to our latest survey of 3,245 Russians in December, just 8 percent think Russia should send military forces to fight against Ukrainian government troops there. Only 9 percent think Russia should train or equip separatist forces with Russian arms.”

However, Putin’s approval rating has recently soared to nearly 70%, but Arik Burakovsky finds this unlikely to last. Burakovsky explains that, “The Russian public largely believes that the Kremlin is defending Russia by standing up to the West,” that “Few people in Moscow heard the drumbeat of war until mid-February. Russian state media has issued continuous denials that the Kremlin was preparing for war with Ukraine. Russian talk shows regularly mocked Western predictions of a looming invasion into Ukraine as ‘hysteria’ and ‘absurdity.’”

“Half of Russians blame the current crisis on the U.S. and NATO, while 16% think Ukraine is the aggressor. Just 4% believe Russia is responsible,” Burakovsky said.

How long Putin can maintain the image of Russia as “a besieged fortress, constantly fending off Western attacks,” as more Russian troops die, with Ukrainian officials claiming 5,710 Russian deaths as of Mar. 1—though Russia claims only two casualties, both Chechens—may be a factor in Putin’s frustration. The longer the war lasts, the harder it will be on the Russian economy and the more his popularity and regime will suffer.

Looking Forward

“Western officials have expressed deep concern that frustration at a long delay in capturing Kyiv may lead to Vladimir Putin ordering the use of weapons capable of causing huge loss of lives, including thermobaric missiles,” according to The Independent.

Kyiv, whose name was previously most often transliterated from Russian as Kiev, but recently has instead been transliterated from Ukrainian as Kyiv, and which is less than 70 miles from the border with Belarus, where pro-Russian dictator Alexander Lukashenko reigns, is considered a central aspect of Putin’s plan by Western officials. On Feb. 24, The Independent reported that “Kiev ‘could fall to Russians within hours as Ukraine air defenses eliminated,’” highlighting the magnitude of the Ukrainian resistance, as well as Russia’s unexpected difficulty in procuring air supremacy.

“On the battlefield, Russia is suffering heavier losses in personnel and armor and aircraft than expected. This is due in part to the fact that Ukrainian air defenses have performed better than pre-invasion U.S. intelligence assessments had anticipated. In addition, Russia has yet to establish air supremacy over Ukraine…

Together, these challenges have so far prevented the quick overthrow of major Ukrainian cities, including the capital, Kyiv, which U.S. officials were concerned could play out in a matter of days. The city of Kharkiv near Ukraine’s border with Russia also has not fallen to invading forces, which officials worried could happen on the first night of an invasion…

These officials noted that Russian forces still greatly outnumber Ukrainian forces, and Russia continues to maneuver these forces into position around major urban centers. It’s also unclear how much of the slower movement can be attributed to the logistical challenge of moving such a large force,” CNN reported in a succinct and informative article on Feb 26.

According to the AP, “President Vladimir Putin hasn’t disclosed his ultimate plans, but Western officials believe he is determined to overthrow Ukraine’s government and replace it with a regime of his own, redrawing the map of Europe and reviving Moscow’s Cold War-era influence.”

Similarly, Reuters reported “The United States believes Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is designed to decapitate Ukraine’s government.”

Putin has stated that his goal is “the demilitarization and denazification” of Ukraine, inciting claims of genocide against Russians by the “Kyiv regime.” These claims are absurd, and inform more about Putin’s propaganda message to Russians rather than his actual goals, according to Vox.

As of Mar. 1, 2022, while Ukraine has fared well so far, at least relative to what was expected, Director of Russian Studies at the Center for Naval Analyses Michael Kofman makes the important observation that “Russian losses are significant, and they have had a number of troops captured, but they have been advancing along some axes. In general, Ukrainians are posting evidence of their combat successes, but the opposite is less true, distorting the overall picture… In a desperate effort to keep the war hidden from the Russian public, framing this as a Donbas operation, Moscow has completely ceded the information environment to Ukraine, which has galvanized morale and support behind Kyiv. Another miscalculation.” Additionally, he said that he “won’t comment on the host of official claims made in this war so far, except that [he] think[s] Kyiv is doing a great job shaping perceptions & the information environment. That said, folks should approach official claims critically in a time of war.”

How Ukraine fares in its war against a significantly larger enemy is impossible to predict. Similarly, understanding why Putin has decided to invade Ukraine is extremely difficult to decipher, more than one might expect. Differentiating the real reasons from the red herrings, or merely incorrect guesses, is compounded in difficulty by the fact that the decisions are ultimately made by a single man. Additionally, since the invasion has begun it is increasingly difficult for me to provide Putin’s excuses as the mere act feels like tacit support of his worries as legitimate. While some have argued that NATO should have heeded Russia’s warnings of eastward expansion, NATO has not forced itself on nations. Likewise, Russia’s invasion of a free, sovereign country is not justified by NATO expansion. It’s not about Ukrainians, or even Russians, it’s about great powers’ maneuvering for more power and one man’s pride. It’s a horrific sight, completely unnecessary and a blow to whatever optimism about the future of global politics anyone could conjure prior to it.