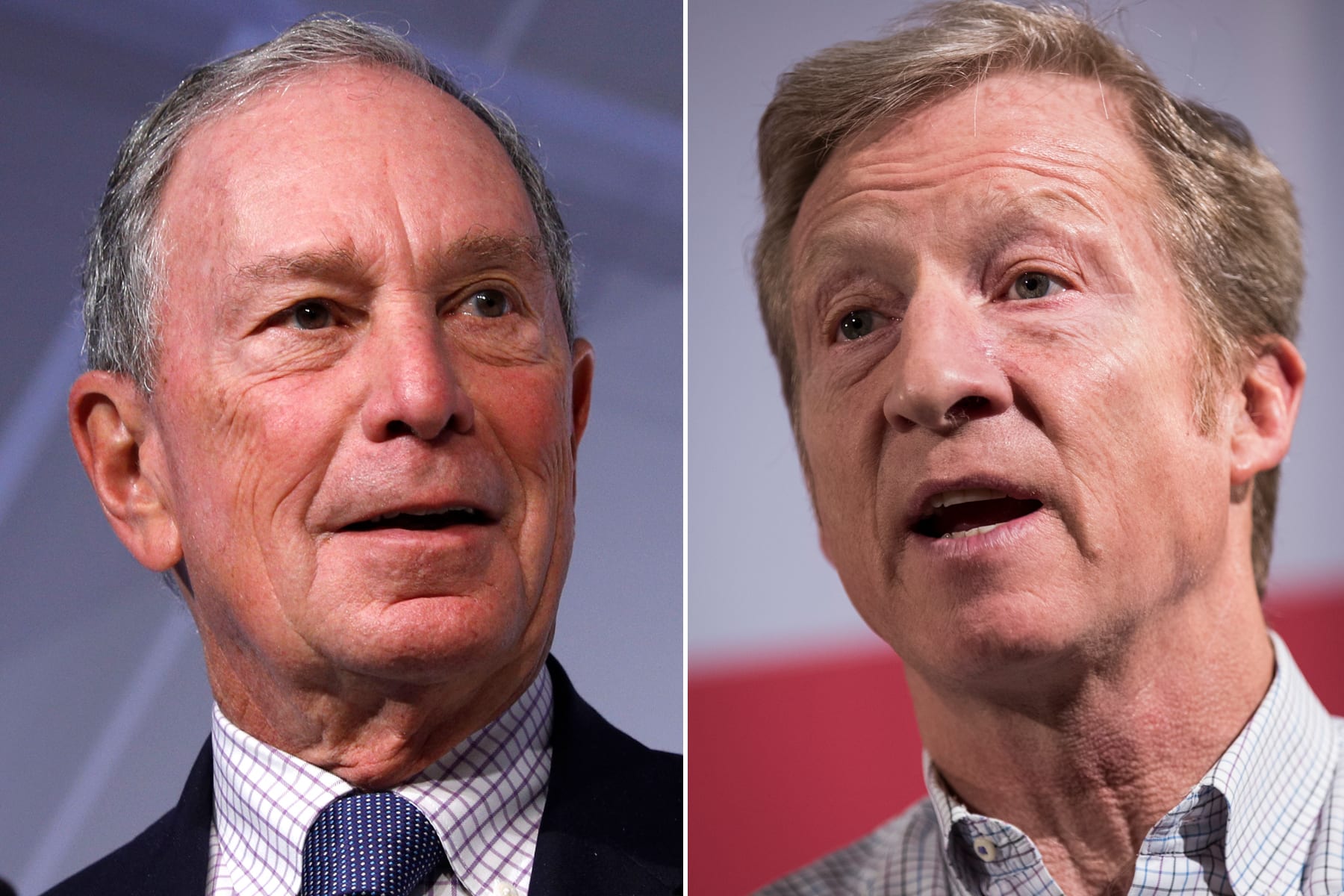

Income inequality has become an important issue in the Democratic primary, with candidates such Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in particular lamenting the role and wealth of billionaires in American life. In sharp contrast to their denunciations, Michael Bloomberg, the twelfth richest man in the world and ninth richest in the United States with a net worth of $61.8 billion, has entered the race and taken a prominent position, neck-and-neck with Vice President Joe Biden for second place. Also in the race is fellow billionaire Tom Steyer, with a net worth of $1.6 billion, who is currently polling seventh in the race with around two percent of the vote, behind Senator Amy Klobuchar and just ahead of Representative Tulsi Gabbard.

As of Feb. 21, Bloomberg has spent $409 million of his own means on his campaign since the start of 2020. Immediately, this differentiates his campaign from a traditional presidential bid, which relies on donations from individuals and political action committees (PACs) to sustain itself, with candidates typically using comparatively little of their own wealth to spread their message. Bloomberg has not taken any donations, and has relied solely on his own resources. Bloomberg has spent by far the most money of any candidate, with Steyer spending the second most at $253 million and Sanders spending the third most at $117 million. Steyer’s funding has come from a mix of donations and his own wealth, while Sanders has relied on mostly small-dollar donations.

Steyer’s strategy has been fairly typical, though his campaign had focused even more on the early states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina than other campaigns. As of Feb. 21, Steyer has spent 68 percent of all the advertising money in South Carolina.

Bloomberg’s electoral strategy is as unorthodox as his finances. Bloomberg has chosen to stay out of the first four primary states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina. Bloomberg will not appear on any ballot until March 3, on “Super Tuesday,” when Alabama, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont and Virginia will determine their delegates. A total of 1,357 out of the 3,979 pledged delegates will be assigned that day. March 3 will be the make-it-or-break-it moment for Bloomberg; his campaign has targeted those states with an unprecedented barrage of advertising.

“Nobody’s done anything like what he’s doing,” Professor of Political Science Keith Fitzgerald said. “Trying to do this primary through TV ads in so many states, nobody’s ever done that before. [His campaign staff] is really good. And the way they sort of combined social media with the TV is really good. They’re hiring good people for the ground game.”

Bloomberg has faced strong resistance from the candidates currently in the race. At the Feb. 19 debate, the five other candidates on the stage (Biden, Warren, Sanders, Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg ) each took the time to press Bloomberg on a wide variety of subjects. From his policy of “stop-and-frisk” during his 12-year tenure as mayor of New York City, to alleging that he is trying to ‘buy’ the nomination, the very ethics of having $60 billion and addressing a problematic history with women, the established candidates struck back against the insurgent Bloomberg. Warren’s opening statement was particularly aggressive against him.

“I’d like to talk about who we’re running against—a billionaire who calls women fat broads and horse-faced lesbians, and no, I’m not talking about Donald Trump, I’m talking about Mayor Bloomberg,” Warren said.

Warren would later press Bloomberg on his company’s use of nondisclosure agreements, “racist policies like red lining and stop-and-frisk” and his tax returns, though she would qualify in her opening statement that she would support Bloomberg if he won the nomination.

“I think that debate revealed clearly that he’s going to have a hard road in front of him,” Fitzgerald said. “I think he gave the impression that he thought this was going to be easy, and that the other candidates would see the logic of why he should be the guy and just sort of step aside. So they came out and smashed him, which is exactly what he should have expected.”

Information for this article was collected at realclearpolitics.com, fivethirtyeight.com, wsj.com, abcnews.com, reuters.com, thehill.com and npr.org.