On Apr. 26, 1986 Chernobyl’s number four reactor, located near Pripyat in the north of Ukraine SSR, failed due to flaws in testing which caused a reactor meltdown and displaced around 350,000 people within the 2,800-square-kilo exclusion zone. In the exclusion zone around the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, abandoned buildings and desolate landscapes are common sights, but where man can’t survive, man’s best friend has thrived. Packs of dogs roam the streets, foraging for food and seeking shelter in the abandoned buildings. And now, new research sheds light on the genetic makeup of these canine communities.

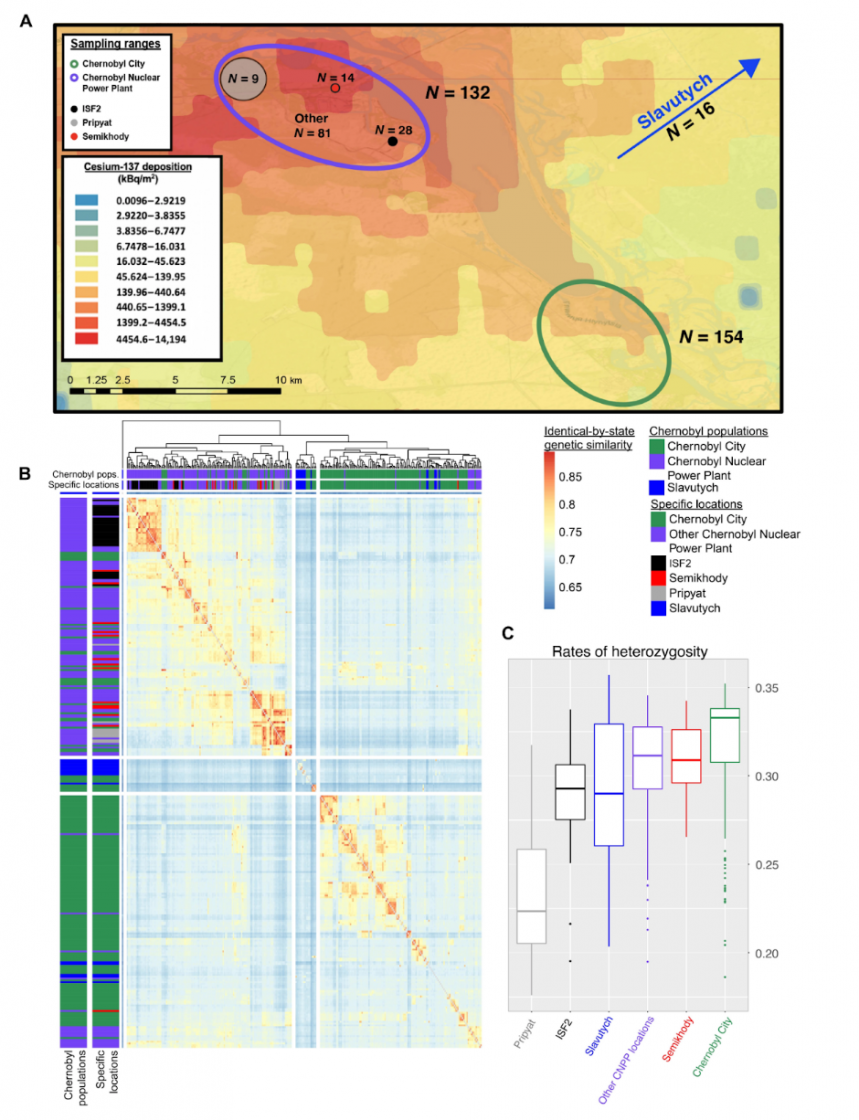

Scientists recently published a study detailing their analysis of the genetic material from a group of 302 free-roaming dogs living in the exclusion zone. The team collected samples using non-invasive methods, such as hair and saliva, and analyzed the DNA to determine the dogs’ ancestry and genetic diversity.

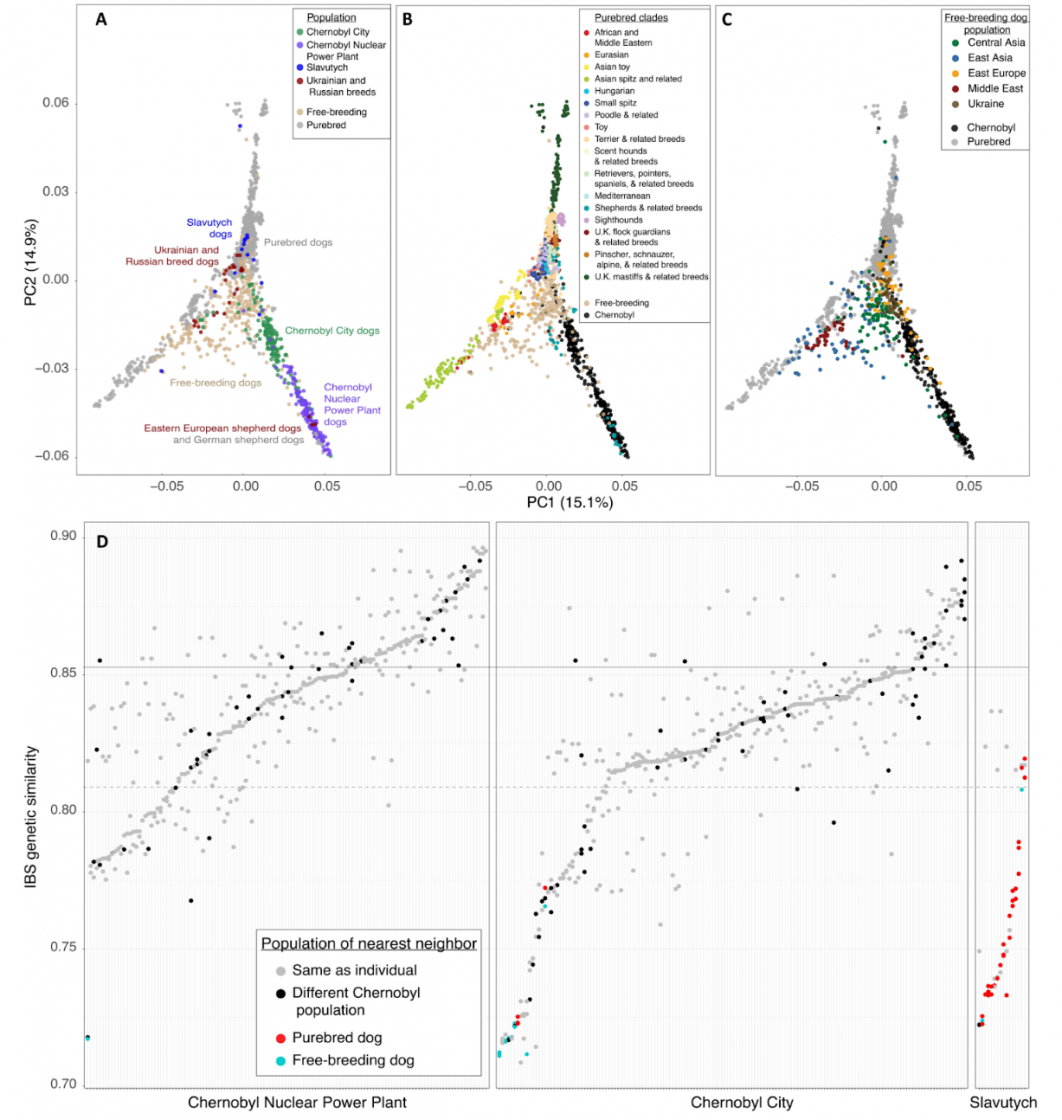

“We first sought to determine whether the dog populations in the CNPP, Chernobyl City and Slavutych are genetically differentiated and, if so, to quantify differences in relatedness,” the authors of the study wrote. “We found, first, that there are three genetically independent populations, such that the majority of individuals cluster in the heatmap based on capture location, with dogs from each location more closely related to each other than to those from other locations. However, there is some overlap, as 27 dogs sampled in Chernobyl City cluster with dogs sampled in the CNPP. In addition, 16 dogs from the CNPP and 5 from Slavutych cluster with the dogs from Chernobyl City.”

Their findings reveal a surprisingly diverse genetic landscape. The dogs in Chernobyl are not a single homogeneous population, but rather a mix of breeds with varying levels of genetic similarity. The researchers found that the majority of the dogs were a mixture of various breeds, including German Shepherds, Siberian Huskies and other local breeds.

One surprising discovery was that the dogs in the exclusion zone had a higher genetic diversity than other populations of dogs in the region. This could be due to the fact that the dogs in Chernobyl have not been selectively bred, unlike many other populations of dogs that have been bred for specific traits, such as hunting or herding.

“To provide a comparison to purebred populations, we used genetic data from 1,324 dogs from 162 breeds recognized by the Fédération Cynologique International, which are largely of western European descent (15),” the study explains. “ The 162 breeds were organized into clades of related breeds based on a bootstrapped phylogenetic tree of only purebred dogs, and the clades were named according to their general function or breed type for ease of comparison.”

The study also found that the dogs in Chernobyl have a higher frequency of mutations in their DNA. This could be due to the radiation exposure in the area, as radiation has been known to cause genetic mutations. However, the researchers noted that the mutations they found were not necessarily harmful to the dogs and could even provide an advantage in the harsh environment of the exclusion zone.

The dogs in Chernobyl have been living in the area since the nuclear disaster in 1986. Many of the dogs are believed to be descendants of pets that were left behind by evacuees, while others are thought to have been born in the exclusion zone. Over the years, the dogs have formed packs and learned to adapt to the harsh environment.

While the dogs in Chernobyl have been studied before, this new research provides a deeper understanding of their genetic makeup. It is worth noting that the study of dogs in Chernobyl could provide valuable insights into the genetics of canines and the effects of radiation exposure on animals in general.

The researchers also highlighted the importance of conservation efforts for the dogs in Chernobyl. While the dogs are currently thriving in the exclusion zone, their long-term survival is uncertain. The researchers noted that there are concerns about inbreeding and the potential impact of radiation exposure on their health.

Efforts are already underway to provide medical care and food for the dogs in Chernobyl. The Clean Futures Fund, a non-profit organization, has been working to provide veterinary care and vaccinations for the dogs. The organization also runs a spay and neuter program to help control the population and prevent inbreeding.

The dogs in Chernobyl may be a surprising sight in the exclusion zone, but they have adapted to life in a place where few other animals can survive. Their genetic diversity and resilience could provide important insights into the effects of radiation exposure on animals and the evolution of canines. As scientists continue to study these remarkable dogs, conservation efforts will be crucial to ensuring their long-term survival.