On Friday, Oct. 15, students rallied outside College Hall within view of President Okker’s office. Displaying bold signs and speaking with passion, they condemned New College’s continued use of Roundup, a powerful chemical herbicide produced by the controversial corporate titan Monsanto. This gathering marked the first significant on-campus protest held by students this year. Yet, the issues students raised were not new. The conflict between students, faculty and administration over the appropriate use of chemical herbicides, the evidence of their harmfulness to humans and their environmental impact goes back years.

This struggle emerges out of a broader global trend decrying the use of Roundup in public areas. After the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) declared glyphosate, the active chemical compound found in Roundup products, to be carcinogenic, dozens of countries, states, cities and schools opted to ban its use. Even in Florida, places like Miami, Fort Myers and Key West have outlawed the use of glyphosate on state property. In Sarasota specifically, City Commissioners have discontinued its use in city playgrounds and dog parks.

The New College Physical Plant has steadily maintained that Roundup is safe to use, citing two sources. The first is the product label that declares it “relatively non-toxic for animals.” The second is the Environmental Protection Agencies’ (EPA) steadfast denial of any causal relationship between its labeled use and the development of diseases such as cancer. While the EPA has made significant contributions towards preserving food, water and air quality since its creation in 1970, it is also true that the integrity of its science has wavered from political interference before. The Intercept described the EPA’s behavior under the Trump Administration as “four years in which political and corporate interests routinely prevailed over law and expert knowledge.” It is no wonder that many find the EPA’s opposition to the WHO’s findings on glyphosate to be suspect, particularly when the research the EPA cites may have connections to the biochemical industry.

“We should listen to the experts,” former Caples Garden TA Deric Harvey (‘20) said. “But what I don’t get is you have a student body that is deeply involved in this research, and you don’t give them any credit. I’ve gone and looked at 20 articles and read them through that show that it’s definitely a carcinogen, it definitely affects the microbiome of the soil, which we know is the gut health of the planet. And the list goes on. All they do is say, oh, Monsanto says it’s good to use. We better believe them and disregard every other thing, any unbiased information about the product.”

Harvey spearheaded the effort in Feb. 2020 to open up channels of communication between groundskeepers and students. Hoping to express student concerns and positively transform school policy, he released a proposal to reduce the amount of herbicide utilized on campus and create more transparency over its use.

After the proposal, students reached an unofficial truce with Physical Plant to limit Roundup application to ornamental flower beds, so long as groundskeepers place warning signs after spraying an area. However, the Physical Plant has since reneged on its agreement. Roundup use has returned to its previous levels, with Physical Plant groundskeepers broad spraying the chemical underneath trees, around buildings, along fence lines, in stormwater ditches, on the brick paver pathways and in the upland areas right next to the bay, all without any signage.

Students emphasized that glyphosate is hazardous to humans and that by spraying it in these areas, glyphosate will undoubtedly leak into the bay. Its use, they say, could lead to a host of grave ecological issues, such as contributing to red tide and the ongoing extinction of Florida manatees.

“In my opinion, Roundup is an incredibly dangerous chemical,” thesis student Olympia Fulcher asserted. “Not only have there been several lawsuits linking Roundup use to different types of cancers, but the herbicide will inevitably runoff into the bay, which is one of the leading causes of algal blooms like red tide.”

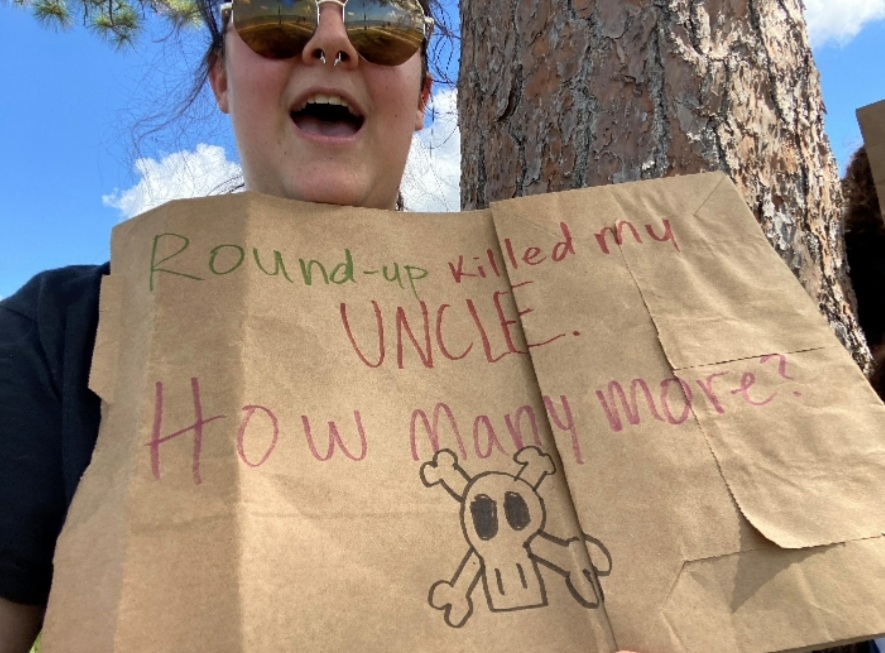

Fulcher then went on to describe their personal story about the potential human cost of using Roundup.

“My uncle, Mike Carroll, died in 1990 of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” Fulcher explained. “Mike had a commercial cattle farm, and we now know that commercial-grade Roundup is connected with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, as well as multiple other types of lymphoma. His children were very young when he died, as was his wife, my aunt. As of writing, she has not chosen to act on the class-action lawsuit against Monsanto for personal reasons. However, after looking at the suit, I am positive that the spraying of commercial-grade Roundup is what caused Mike’s death.”

An employee of the school, whose name has been redacted for confidentiality, confirmed Physical Plant is spraying Roundup in these areas and strongly disapproved of its use.

“We shouldn’t be spraying in the uplands,” the employee exclaimed. “We’re right here by the bay! We shouldn’t be spraying the ditch area around the letter dorms. They run into the bay. It just does. [We should be spraying] only flowered ornamental beds, the places where you see large shrubs.”

The employee went on to warn against some of the dangers of applying herbicide to open areas. They claimed that when sprayed around trees, it creates a phenomenon known as “drift,” where the herbicide is kicked up and coats the surrounding grass. Splotches of withered yellow grass give away zones affected by drift.

“Herbicide drift is a real issue,” Harvey commented. “Especially if it’s windy or something, but it drifts no matter what. Even if you just spray it in one area, it’s still going to off-gas a bit and it’s going to drift. Once it’s sprayed in the environment, it’s in the environment. And although they say that it breaks down quickly in UV light, it’s still in the area, the energetics of the chemical and all.”

Yet, students needed no confirmation to infer what was causing the withered grass and expressed horror at this being allowed on a bare-foot-friendly campus.

“I used to walk around this campus barefoot in bliss,” third year student, protester and Council of Green Affairs (CGA) member Lilian Field related. “But now I’m always looking out for the brown spots where it’s clear that Roundup has been used nearby.”

Following the protest, Physical Plant again agreed to use signs that warn students and faculty when herbicides are used. However, according to the employee, there’s a reason they stopped using the signs in the first place, and a reason they spray Roundup early in the morning. He indicated that it’s an intentful policy meant to veil Physical Plants’ use of herbicides from the student body.

“[They] said, we’ve just got to get out there and spray before the students come out, so they don’t see it,” the employee revealed. “All the signs that we had with the agreement have disappeared except for one, and it’s broken.”

“The claim that the chemical spraying is done in the early morning at 6:00 a.m. is correct,” Associate Director of the Physical Plant Curtis Davis wrote in response to this claim. “The Grounds staff start their shift or workday at 6:00 a.m., so they typically tackle tasks that don’t disturb our campus community (weedwhackers, mowers, etc.) at the beginning of the shift. Additionally, handling that task early in the morning allows it to dissipate and dry, thereby reducing the impact, as few are moving about that early.”

Despite frustration at the Physical Plants herbicide policies, students still expressed sympathy for the difficult work groundskeeping entails. But they claim the options they offer would be just as if not more efficient as Roundup, in addition to being significantly safer for workers and students.

“Mulch acts as a natural and free weed suppressant,” Harvey wrote in his proposal to the school. “By raking leaves and spraying chemicals, two jobs are created where there could possibly be none. There’s free mulch everywhere in this town.”

“Impervious surfaces like pavers can be difficult to weed,” Harvey continued. “Still, synthetic herbicide treatments are not necessary. Rock salt is quite effective at killing weeds, as are vinegar solutions.”

The employee also conveyed support for non-taxing alternative methods for groundskeeping.

“You don’t have to go around spraying Roundup,” the employee said. “With just a little bit of inexpensive solution, just saltwater and dishwashing soap, you can handle weeds. That’s all you need. It works. And Roundup is probably, what, 2000 times more expensive? I mean, really.”

When asked whether the use of Roundup helps keep workers safe, as the schools administration claimed in an email defending its use, the employee expressed derision at the idea.

“You don’t have to use Roundup,” the employee stated. “You don’t have to. That’s number one. There are no situations, none, made safer by using Roundup. None at all. The danger is in using that stuff.”

While progress on this issue has been inconsistent, the onset of the new administration may have opened more opportunities for change. Okker came down from her office to talk to protesters and has since expressed sympathy towards their aims—if students and faculty can present a convincing case at the next Landscape Meeting slotted for some time in early November, she may issue a policy change that could end New College’s widespread use of Roundup.

“My understanding is that there was no administrative decision [by the previous administration on Roundup],” Okker said, implying the last changes didn’t stick because there was no concrete policy directive. “There were recommendations, but there was not actually a decision to make a change about Roundup.”

“I would not have asked the landscape committee to review this if I wasn’t open to what their recommendations would be,” Okker continued. “Now, I don’t know what the recommendations will be. And I don’t know what I’ll be convinced by yet. It’s a difficult decision, a difficult situation. And I’m going to be fully transparent about it. So if we make a decision to actually have a change in policy, I’ll announce it, and we will abide by it.”

Field responded with optimism when asked about the upcoming Landscape Meeting to discuss the future of groundskeeping at New College.

“I want to direct everyone’s focus to our power as students to create lasting change in our new college community and beyond,” Field said. “Every microcosm reflects into the macrocosm and vice versa. If we support sustainable land care here, it will ripple out into our greater Earth community.”

“Everything we do has an effect, and if it’s killing plant members of our ecosystem, it’s killing us too,” Field continued. “At the end of the day, there’s always another way. We now have the opportunity to show up for the type of campus community we want to be a part of, and with enough student support and solid evidence at the next landscaping meeting, we will get this changed.”

This is the first in a two-part series about Roundup use on campus. Read the second part, which focuses on worker safety and the legal infrastructure surrounding Roundup use here.