The most famous origin tale of the Chinese Zodiac animals suggests that the outcome of the Great Race determined the order of the Zodiac animal years.

Chinese sociopolitical artist Ai Weiwei has used the lore of the Chinese Zodiac animals in a few of his works across the years. His 2011 series of bronze sculptures, “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads,” was shown at the Ringling Museum of Art from 2017 to 2018. His 2018 series of portraits of the animals made from Legos, “Zodiac (2018) LEGO,” is currently on display at the Ringling Museum until Feb. 2, 2020.

The story of the Chinese Zodiac animals goes as far back as 206 B.C. to the Han Dynasty. The most famous story involves the Great Race, in which twelve animals competed in a tournament to reach the Jade Emperor to determine the order of the Zodiac animal years. At the end of the race, the order determined the rat was first, then the ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig.

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 in Beijing, China to a poet father who was denounced during the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which targeted anti-communists in China from 1957 to 1959. In 1958, his family was sent to a labor camp in Heilongjiang because of his denouncement against his father. Ai’s family moved back to Beijing shortly after the death of Mao Zedong during the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s. During this time, Ai attended film school and studied animation. From 1981 to 1993, Ai lived in New York City and became friends with renowned poet Allen Ginsberg. In 1993, he moved back to China and still resides there today.

The heads in both of Ai’s exhibits are stylized in a manner reminiscent of the famous Zodiac heads from the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, China. The original Zodiac animal heads were arranged to form a clock around a fountain designed by European Jesuits in the 18th century for the Qianlong Emperor. British and French soldiers looted the heads in the late 19th century.

Ai chose to portray the Zodiac animals in order to critique Chinese nationalism and the Chinese Communist Party. Strategically placing these heads in Western spaces was an “ironic act,” according to Ai. The nationalism of 20th-century China did not reflect the quality of life seen by Chinese citizens, especially those with anti-Communist values. This can be seen in Ai’s rough upbringing that resulted from his father’s rightward political orientation.

In May 2011, Ai was detained for 81 days by Beijing security officers cracking down on out-spoken liberals since he was one of the biggest critics of the Chinese Communist Party. During his detention, Ai was kept in a small room under constant surveillance. A fellow detainee, lawyer and friend of Ai named Liu Xiaoyuan spoke to the New York Times in 2012, saying, “[Ai’s] personality is, ‘The more you push me, the harder I’m going to push back.’”

Ai’s anti-Communist ideals have made their way into his art many times, including in his 2008 installation called “Sunflower Seeds” at the Tate Modern in London, England. This installation consists of 100 million hand-crafted porcelain sunflower seeds, which represented followers of Mao Zedong. Mao often referred to his followers as his sunflowers. The work commented on conformity and commercialism in China: up close, one could tell apart each tiny seed, but from afar, all the seeds melded together. Ai chose porcelain because of its ties to the commercial history of Chinese artisans. This installation has been featured in twelve exhibitions in art galleries across the world between 2009–2013.

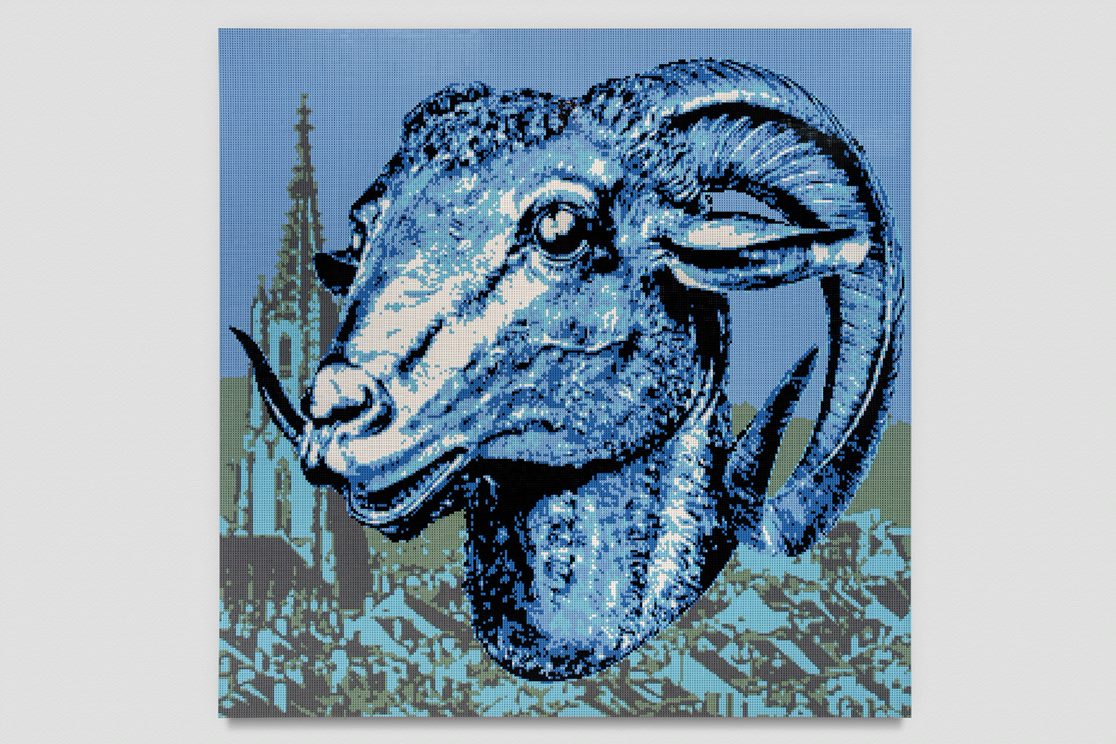

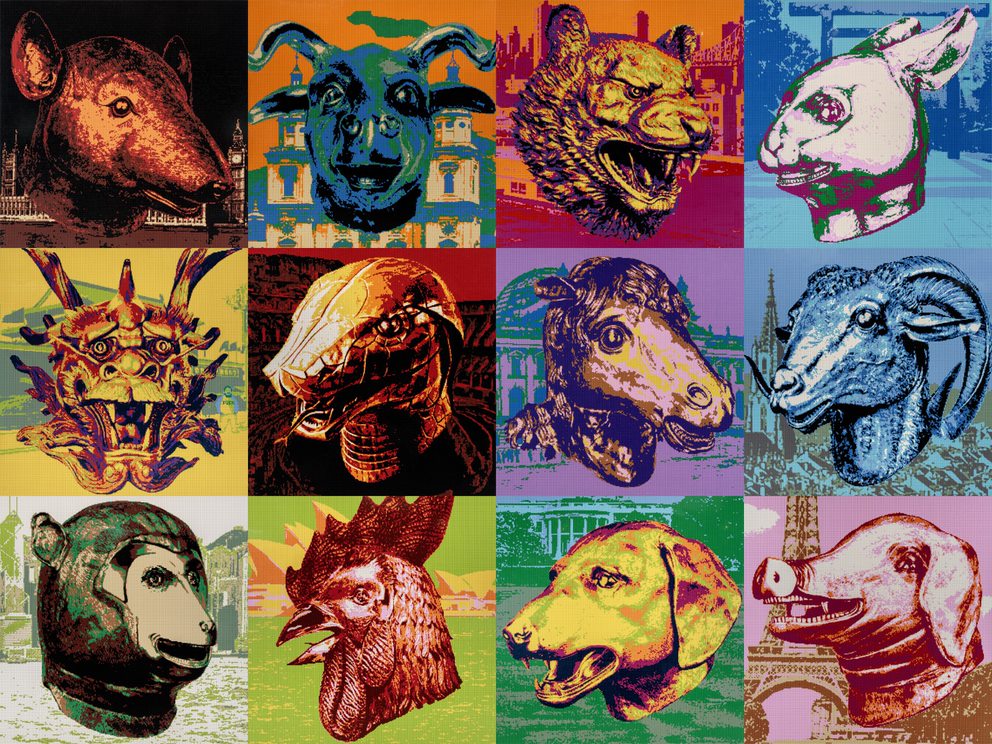

His current exhibit in the Ringling Museum of Art, “Zodiac (2018) LEGO,” follows the same themes as his previous Zodiac series. “Zodiac (2018) LEGO” features twelve portraits of the Zodiac animals made of Legos. Each is stylized the same as Ai’s “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads” exhibit, mimicking the Zodiac heads of the Old Summer Palace again. In the background of each portrait is a famous city. For example, London, England resides behind the rat; Sydney, Australia behind the rooster; and Beijing, China behind the dragon. The inclusion of famous locations, the majority of which are Western, speaks to Ai’s aforementioned “ironic act.” In the portrait of the dragon, Ai put himself in the background, with the word “Fuck” written on his shirt. This may represent his complicated history with the Chinese government.

“The ‘Zodiac (2018)’ series continues Ai Weiwei’s tendency toward the accumulation of materials, a creative method the artist has employed for many of his best-known works,” the Ringling Museum wrote on their official website. “His interest in amassing and collecting connects with his ongoing interest in how individuals relate to society through experience. Ai Weiwei’s use of Lego bricks, usually considered a children’s toy, is a poignant example of his singular art practice and the reconfiguration of this basic material, transforming the narrative and nature of this medium.”

All of Ai’s works use China’s painful past and his involvement in it to comment on the political present. Professor of History and International and Area Studies Xia Shi specializes in Chinese history.

“Only when we understand the past, we can truly understand the present,” Professor Shi said. “China experienced much tumult throughout the 20th century. Some of the central themes of its history during this period, such as revolution, reform and modernization, continued to play out in today’s China. History might not necessarily repeat itself, but learning China’s history in the 20th century can help us better understand the longer roots and patterns of its contemporary phenomenon.”

Information for this article was gathered from nytimes.com, npr.org, tate.org and ringling.org.