Since 1999, more than 500,000 people have died from opioid overdoses in the U.S.—the victims of America’s opioid epidemic. In the 2010s, state and local governments filed thousands of lawsuits against companies that make and distribute the drugs seeking to hold them accountable. A handful of cases have gone to trial, but many more have been settling, particularly over the last year.

In Florida, CVS and three other pharmaceutical companies agreed to pay a combined $860 million as part of a settlement on Mar. 30, with CVS paying $484 million.

“As a result of the agreement, CVS Pharmacy will no longer be a defendant in Florida’s opioid lawsuit that is scheduled for trial in April 2022,” according to Reuters.

That trial opened on Apr. 11, against Walgreens, who has thus far chosen to fight the case and not settle. According to the Associated Press, “the state’s case hinges on accusations that as Walgreens dispensed more than 4.3 billion total opioid pills in Florida from May 2006 to June 2021, more than half contained one or more easily recognized red flags for abuse, fraud and addiction that the company should have noticed and acted upon.” Similar charges would have been brought against CVS had they not settled out of the case.

Walgreens’ defense looks to focus “on how manufacturers such as Purdue Pharma misled pharmacies on opioid addictive properties.” Purdue Pharma are the makers of Oxycontin, and, on Mar. 3, the company agreed to a settlement which “could be worth more than $10 billion over time.” Nationwide, according to an Associated Press tally, settlements and civil and criminal penalties against pharmaceutical companies since 2007 have totaled over $45 billion.

As all of these cases and settlements make the news—regardless of whether they are truly sufficient—the full story of how the opioid epidemic got to this point deserves to be told, particularly given it shows no signs of slowing. Indeed, according to a study published in The Lancet, “the 2020 data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a potent accelerant of opioid-related overdose deaths.”

Opioids come in two classes, opiates and synthetic opioids. Opiates are substances made directly from the opium poppy, which has appeared as a remedy in ancient medical texts, some more than 3,000 years old. Opium is the dried latex from the poppy seed pod, which is traditionally slit open while unripe to allow the sap to seep out and dry on its surface, eventually turning into the dried latex.

The primary examples of opiates are morphine and codeine, and to a lesser extent thebaine and papaverine. Morphine was identified and isolated in the early 19th century, and widely prescribed as a painkiller and antidiarrheal in the American Civil War.

“In the 20th century, drug companies created a slew of synthetic substances similar to these opiates, including heroin, hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl,” according to historian Mike Davis.

Opioids are highly effective painkillers, especially in the short-term, but are also highly addictive. The reasons for these medications’ high propensity for addiction can be found in their chemistry and in the availability of addiction treatments to addicts. All opioids—while slightly different chemically—act by binding to opioid receptors in the brain. These receptors have a variety of functions, one being the management of pain. Normally, endorphins bind to these receptors to temper pain signals. Opioids do the same thing, but they “bond much more strongly, for longer,” Davis said, allowing them to manage much more severe pain.

However, opioids also suppress the release of noradrenaline, which is responsible for influencing wakefulness, breathing, blood pressure and digestion. Due to its important responsibilities, the suppression of noradrenaline, especially from higher opioid doses, can have dangerous effects, such as decreased heart and breathing rates.

Moreover, the brain develops tolerance, meaning that in the absence of opioids, the natural levels of endorphins are less capable of tempering pain, increasing pain sensitivity and inspiring higher dosages for relief, inciting a feedback loop. Simultaneously, the brain produces more noradrenaline receptors, ergo its noradrenaline sensitivity, so that basic bodily functions can continue. This makes the brain “dependent on opioids to maintain the new balance,” according to Davis. Thus, within just a day of not taking opioids, the surplus noradrenaline produces debilitating withdrawal symptoms.

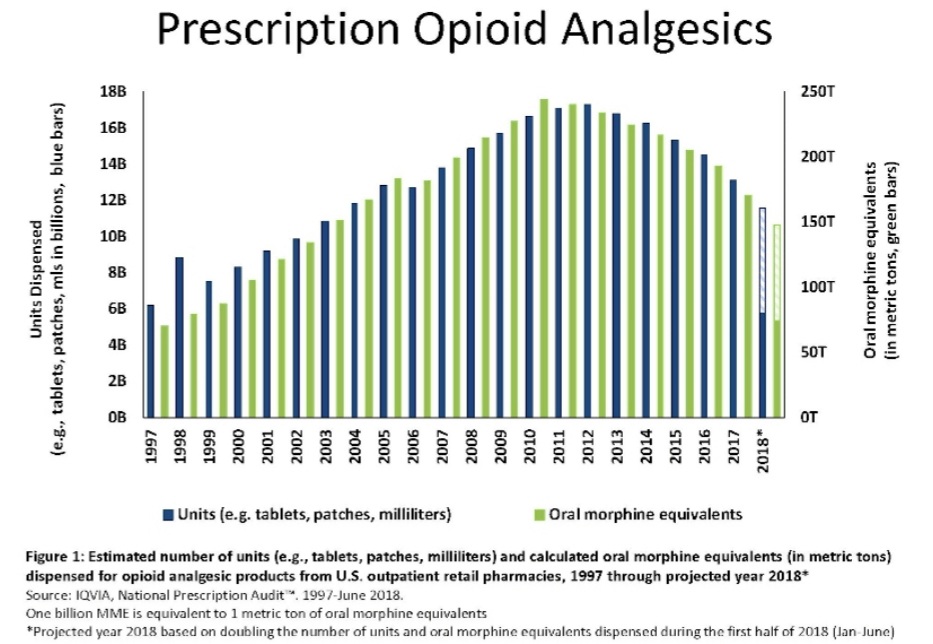

In the 1980s, the roots of the present-day opioid epidemic emerged, “when pain increasingly became recognized as a problem that required adequate treatment [and new laws] removed the threat of prosecution for physicians who treated their patients’ pain aggressively with controlled substances,” according to Nature.

But, in the 1990s, “pharmaceutical companies began to market [new opioid-based products] aggressively, actively downplaying their addictive potential to both the medical community, and the public,” Davis said.

The primary culprit has been pinpointed as PurduePharma’s OxyContin, a sustained-release formulation of oxycodone. Prescriptions and addiction skyrocketed, inaugurating the first phase of the opioid epidemic.

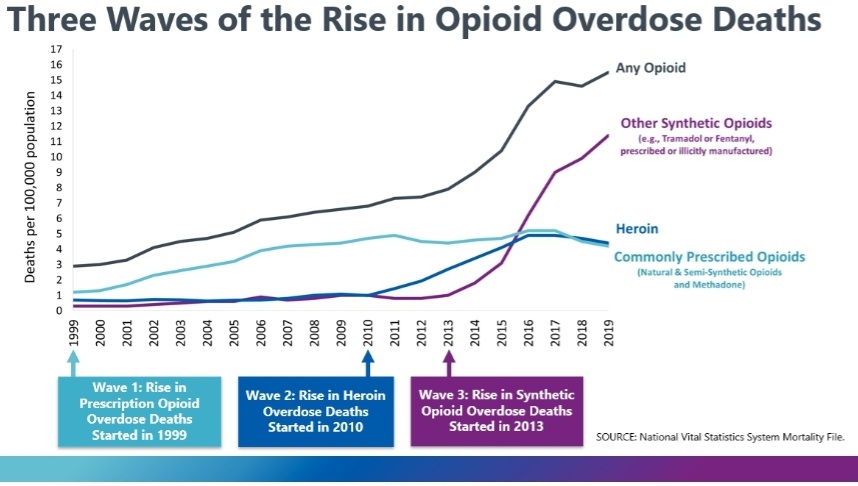

In the late 2000s, those who became not only addicted to these prescription opioids, but dependent on them to avoid the life-threatening effects of withdrawal, often migrated to heroin. In fact, “data from 2011 showed that an estimated 4 to 6 percent who misuse prescription opioids switch to heroin, and about 80 percent of people who used heroin first misused prescription opioids,” according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

NIDA reports that “there is no real difference for the user” between prescription opioids and heroin “when administered by the same method.” However, NIDA also concludes that “a number of studies have suggested that people transitioning from abuse of prescription opioids to heroin cite that heroin is cheaper, more available, and provides a better high.” The first two claims are evidenced, and the last may be reported because heroin is more often injected than prescription opioids—the injection being the reason for the “better high,” not the drug.

The migration towards heroin—specifically the rise in heroin overdoses—defines the second phase of the opioid epidemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

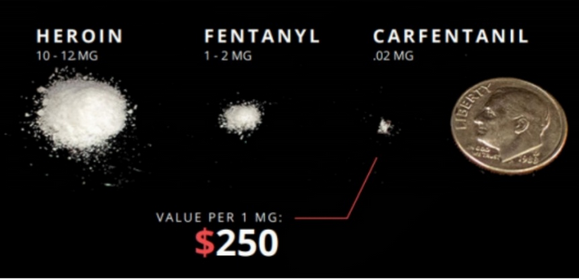

The third phase began around 2013, when “heroin dealers who wanted to increase profits began to mix their products with fillers and fentanyl,” according to Nature. Fentanyl, unlike heroin, really is more potent and consequently more dangerous. Because it’s more potent, it’s cheaper to transport.

Fentanyl is, unlike previously discussed opioids, entirely synthetic. It does not originate from natural opiates like morphine or thebaine, but from the synthetic opioid meperidine. This is also true of sufentanil and carfentanil. Their differing chemistry is the reason for their significantly magnified potency. A 2021 study on the anomalous pharmacology of fentanyl—that is, it’s approximately 100 time more potent compared with “prototypical opioid agonists such as morphine”—suggested a handful of reasons: “its rapid onset of action, in vivo potency, ligand bias, induction of muscle rigidity and reduced sensitivity to reversal by naloxone.”

And, because it’s entirely synthetic, it’s cheaper to manufacture. Unlike heroin, which requires growing poppy plants, extracting opium and converting it to heroin, fentanyl must only be synthesized.

The higher potency of fentanyl means a lower lethal dosage. When the lethal dosage is lower, so is the margin for error. This, in addition to the cutting of other drugs by dealers with fentanyl without informing the customer, is the primary reason for the immense levels of overdoses associated with fentanyl.

“The problem is that not everyone is going out to buy it intentionally—many are in the market for something else, but getting the drug cut with fentanyl,” Alice G. Walton wrote for Forbes. “Or worse, only fentanyl.”

Each phase of the epidemic, however, is more accurately described as three different, coterminous epidemics.

“Basically, we have three epidemics on top of each other,” Keith Humphreys—psychiatrist at Stanford University in California and a former White House drug-policy adviser—said for Nature. “There are plenty of people using all three drugs. And there are plenty of people who start on one and die on another.”