Studies have consistently found that undergraduate students who have a job while attending school show higher retention rates than those who do not work at all. However, these studies also reveal that the benefits of working while still in school cap out when the student works between 10 and 15 hours per week, with retention rates declining among students who average more than 15 hours.

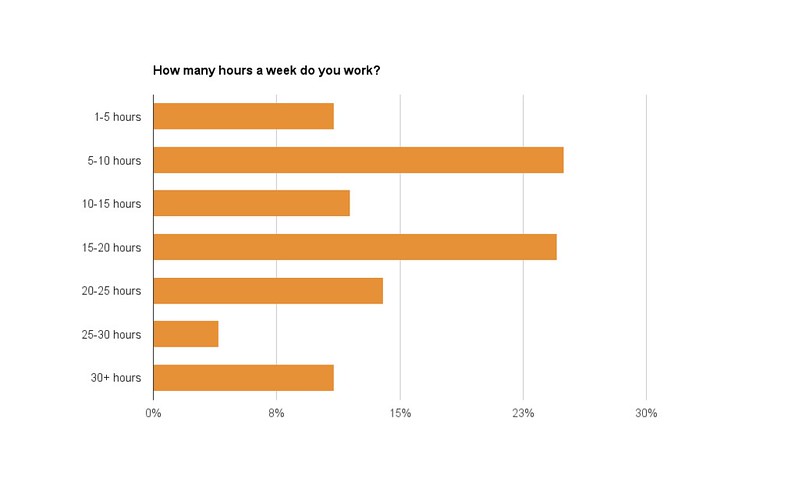

As tuition and living expenses increase, working more than 15 hours a week has become a tiring but necessary reality for many New College students. In a poll conducted by the Catalyst, 75 percent of respondents had at least one job, with some also holding an internship. Of this sample, 52 percent of respondents worked more than 15 hours per week.

“The bottom line is that the way that schools calculate credit hours – given that that’s a problematic way to count things – they usually think you should be spending about three hours outside of class for every hour in class,” Professor of English Literature Miriam Wallace said. “So if you’re doing four classes you’re looking at more than a 40-hour work week already. If you add a 20-hour job to that, something is going to happen. You’re not going to get your sleep, you’re not going to get your exercise, you’re not going to be prepared for class…I would say 10 is the absolute limit. When you get your hours over that something suffers.”

Both Professor Wallace and Professor of Biology Sandra Gilchrist recognize that often times the students working the most hours do not have the option to do otherwise.

“Some students are working because they want to have something, but many others are working because they have to,” Gilchrist said.

Thesis student Madeleine Yount works three on-campus jobs for 15 to 20 hours a week in order to pay rent and buy groceries. Of those who responded, 75 percent said at least one of their jobs was on campus. For Yount, the combination of living off campus and working on campus is a very helpful one.

“Living off campus has really helped. I associate home with either ‘I’m going to study, I’m going to eat or I’m going to sleep here,’ and then I associate school with work or studying,” Yount said. “So having that split kind of makes me order my life more.”

While Yount acknowledged that there are benefits to working, the bottom line is paying rent. “I think it’s good because I like to keep myself busy because then I can’t procrastinate, it’s like a way to check myself, but I get paid, so that’s nice,” Yount said. “But I need to work in order to pay my bills.”

Third-year Cristina Harty works between 20 and 25 hours a week as a hostess at a restaurant. Similarly, Harty needs to work in order to stay at school. “I don’t get an allowance from my parents at all, so I have to work to pay rent and utilities,” Harty said.

Working as student can sometimes be overwhelming. “My manager was having me work on Wednesdays, and on Thursdays I have three of my classes,” Harty said. “So on Wednesday I was getting done with my homework at like three and five in the morning because I was doing it after work.”

Professors also see the effects that working more than a few hours a week can have on students’ performance. “I think that some of them are working way too much and working hours that are not conducive to helping them do the best they want to do,” Gilchrist said. “Students come in and they’re very tired, they can’t think well. You know they know the material but it comes out garbled.”

Both Professor Wallace and Professor Gilchrist worked during college. Professor Wallace worked as a lifeguard through the work-study program and Professor Gilchrist worked a variety of jobs, including bartending.

“I worked the whole way through college, so I can empathize,” Gilchrist said. This empathy leads to many professors being understanding of the stress and time constraints of those students who work.

“I’m taking a fairly hard psychology class – Analyzing Conversation – and so I’ve been falling behind in that class because of the whole Wednesday situation,” Harty said. “So last week I emailed the professor at five o’clock in the morning after doing the assignment that was due the next day for class and I still hadn’t finished the makeup assignment from last week, because last week I had gone to bed instead of doing my homework. She was very understanding.”

Professors are often seen as more understanding of students as workers than employers are understanding of employees as students.

“Last semester I was continually scheduled at 3:30 and I had a class that ended at 3:20, and instead of telling my manager I just left class early because I couldn’t see my employer being understanding of that,” Harty explained.

Professor Wallace explained situations like this saying, “Immediate demands from someone who has authority over you is always going to feel more pressing, and professors are often more flexible.

“And it’s very hard when you’re in the middle of it and you have a job that’s going to fire you if you don’t show up. That can feel more pressing than what you’re really here to do, and what you’re really here to do is go to college,” Wallace continued.

While Harty recognizes that, at times, her academics suffer at the expense of working, she tries to keep things in perspective.

“I’m trying not to let my academic life suffer, but I realize that my grades are just going to suffer,” Harty said. “And there’s a lot of students like me, who realize that our evaluations are not going to show our full potential because we’re super tired all of the time. And I’ve had to learn to forgive myself, like, it’s not my fault that I live in a society where I have to work in order to live and go to school.”

Both professors encouraged students to communicate the amount that they are working with their professors and advisors.

“It helps advisors a lot if students let us know how much they’re working. You don’t have to, but if on the contract in the other activities I know you’re working 15 hours a week that gives me a much better picture of how to think about what you’re able to do in your classes and what I see in your evaluations,” Wallace said. “The reason we do the contract, and that we don’t just have the registrar count your hours is precisely because we want to see that whole picture…The more you let your advisor know about the full picture of what you’re committed to, the more we can help you and the less we’ll be surprised when there’s a problem mid term.”