President Donal O’Shea will be travelling to Gainesville to defend the “New College Tomorrow: Arts and Sciences for Florida’s Future” proposal, which requests an additional $700,000 for the 2020–2021 school year, at the Oct. 30 Florida Board of Governors (FBOG) meeting. The proposal focuses on three main initiatives—executing the college’s strategic plan to grow enrollment, inflecting student experience toward the world of work and increasing collaborative agreements with regional institutions—and came to fruition as the FBOG adds an additional funding category to its Education and General (E&G) budget request.

New College is part of the State University System of Florida (SUS), a system of 12 public universities in Florida. Headquartered in Tallahassee, the SUS is overseen by a chancellor and governed by the FBOG.

Every year, the SUS submits an E&G budget request to the Florida Legislature. After the sitting governor submits budget recommendations to the Florida Senate and House of Representatives, the two legislative bodies pass separate budget bills. Differences between the two budgets are negotiated and resolved through a joint public conference. A final budget bill—the General Appropriations Act—is passed by the legislature and sent to the governor, who has line item veto power.

After the governor approves the final bill, the E&G budget is divided among the 12 institutions that make up the SUS.

Performance-based funding: a baseline for all SUS institutions

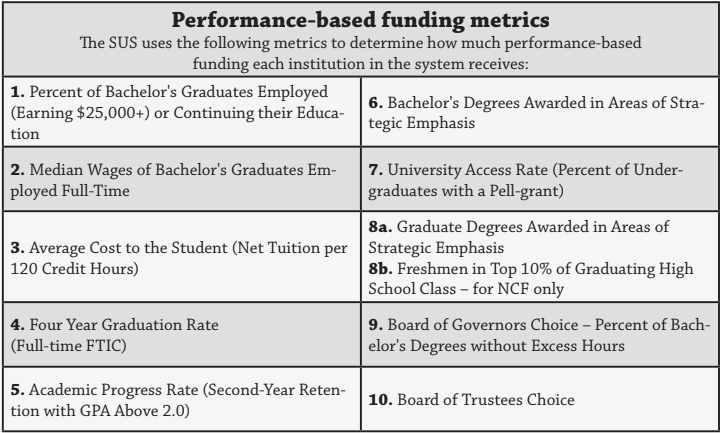

For the 2019–2020 school year, the SUS’s performance-based funding budget totalled $560 million. This money is distributed between the 12 universities in the system based on how well each performs in regards to 10 key metrics.

The model has four guiding principles: use metrics that align with SUS Strategic Plan goals, reward “excellence” or “improvement,” have a few clear, simple metrics and acknowledge the unique mission of the different institutions.

Each metric is scored on a scale of one to 10, resulting in a total score out of 100.

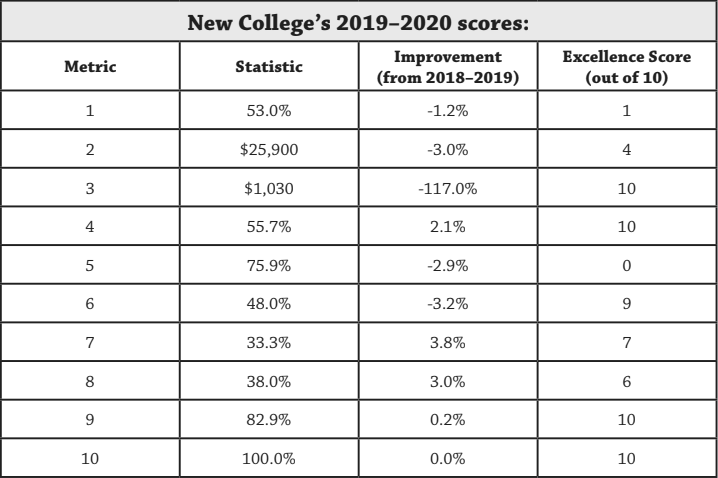

New College is currently the lowest-ranking institution in the SUS, with a total performance score of 67. This statistic marks a significant drop from the 2018–2019 school year, when the total performance score was 75. The highest-ranking institution is the University of Florida (UF), with a total performance score of 95.

For the 2019–2020 school year, New College was allocated $8,337,255 in performance-based funding, the lowest in the state.

“When it comes to performance-based funding, we don’t do as well as we should,” O’Shea said. “I’ve been afraid that we’re going to get called on the carpet for that because it dropped in the past year. We should be doing better on those metrics, there’s no question.”

Of the 10 metrics, seven apply to all 12 institutions. The eighth metric, which measures graduate degrees awarded in areas of strategic emphasis, applies to all institutions except New College. Instead, New College’s eighth metric is “freshman in the top 10 percent of graduating high school class.” The ninth metric regards the percent of Bachelor’s degrees awarded without excess hours and the tenth metric is chosen by each institution’s Board of Trustees to be applicable to each institution’s specific mission.

The first metric, which deals with the percent of Bachelor’s graduates employed or continuing their education further one year after graduation, is one that New College always struggles on.

New College received a score of one out of 10 for the first metric in 2019. For comparison, the second lowest score in the SUS belongs to Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), which scored six out of 10.

“A lot of our students are not so focused on the next 12 months; they’re looking 10 years ahead at what they want to do and try to figure out and put together the various pieces of their lives,” O’Shea said. “New College just attracts students like that. We look better if we look 10 years out.”

Information for this metric is obtained from a variety of external sources, primarily the Wage Record Interchange system (WRIS2). The SUS advocates that they are able to account for approximately 90 percent of SUS graduates, but data from some states—Alabama, California and New York—are not included in WRIS2. Every year, a handful of New College graduates pursue work in these states and are not accounted for in the data.

Even with these circumstances taken into consideration, O’Shea recognizes work needs to be done to improve student outcomes. The SUS reports only 53 percent of New College alumni who graduated in 2019 were employed or continuing their education one year after graduation. The second lowest outcome, from FAMU, was over 10 percent higher than New College at 63.9 percent.

“It’s hard when you had around 50 percent of our students not in graduate school and not earning more than $25,000 14 months out,” O’Shea said. “That number is still way higher than it should be, even taking into account the things that make New College students different. The students have pretty good skills, we should be helping them more.”

Because a substantial amount of New College alumni are not accurately represented in the first metric, the FBOG Budget and Finance Committee is proposing a model change at the Oct. 30 meeting.

The proposed issue is that “smaller institutions experience volatility with the data from these external sources. Thus, there can be significant fluctuations year over year.” The proposed option the committee supports is to “allow institutions with headcount enrollments less than 2,000 students to supplement the WRIS2 data with alumni data for those in non-WRIS2 states.” The supported option mentions the methodology for the supplemental alumni data would need to be approved by Board staff and verified and audited by institutional staff.

“We would love a metric, and we ask for it all the time, for three years out or five years out, and in fact, in this Universities of Distinction title, we’ve proposed one like that as a separate metric,” O’Shea said. “But politicians, they want change immediately, and I get that too. A lot of the Board of Governors are uninterested if someone goes out of state. They’re using state money to stimulate the state economy, and it’s short-sighted, but I get it.”

Preeminent university funding: additional money for the state’s highest-performing research institutions

“The two basic sources of funding are performance-based funding and another stream for preeminent universities,” O’Shea said.

In addition to receiving performance-based funding, preeminent universities receive money from the SUS’s “preeminence and emerging preeminence” budget.

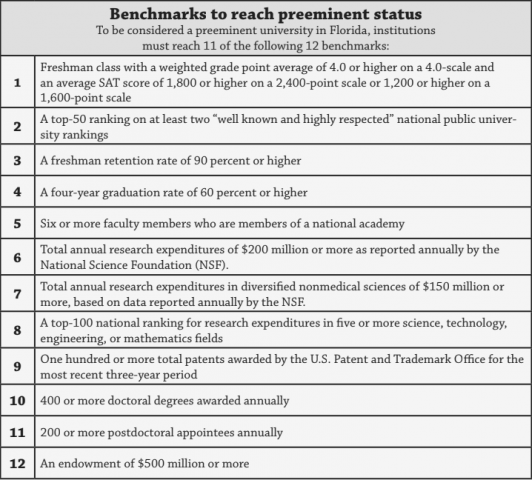

According to Florida Statute 1001.7065, preeminence is determined by 12 academic and research excellence standards, detailed in the attached table. To reach preeminent status, universities must reach 11 of these 12 benchmarks.

Currently, preeminent universities include the University of Florida (UF), Florida State University (FSU) and, most recently, the University of South Florida (USF). The University of Central Florida (UCF) is considered an “emerging” preeminent university and receives additional funding, but does not yet hold the official preeminent distinction.

For the 2017–2018 school year, the SUS’s “preeminence and emerging preeminence” budget totalled $52 million. This figure has been sharply cut, however, declining to $20 million for the 2018–2019 school year and $0 for the 2019–2020 school year.

These cuts come after clashes between the Republican-controlled state House and Senate in early 2019. The House proposed $100 million in across-the-board cuts to higher education funding, with an additional $20 million drop in preeminence funding.

The push by the House to reduce spending was bolstered by questions surrounding spending by preeminent universities, most notably UCF’s misuse of at least $38 million in state funds to build a new classroom/office building. UF also opened an internal investigation into its use of several million dollars in state money to construct a Center of Outdoor and Recreation Education and three Greek housing lots, and USF officials admitted they misused $6.4 million on a building completed in 2010.

According to O’Shea, despite the budget cuts, the SUS plans to request $100 million for the “preeminence and emerging preeminence” budget for the 2020–2021 school year.

Universities of Distinction: the emergence of new additional funding for non-preeminent universities

“This is the Legislature, there are a lot of powerful members, and so they were going ‘well what about the other nine universities?’” O’Shea explained, referencing the non-preeminent institutions. “So they concocted this Universities of Distinction label.”

According to the FBOG, Universities of Distinction is “a path towards excellence that will produce high-quality talent to diversify Florida’s economy, stimulate innovation and provide a return on investment to the state.”

The key goals of Universities of Distinction are to focus on a core competency unique to the SUS and one that achieves excellence at the national or state level, to meet state workforce needs now and into the future, including needs that may further diversify Florida’s economy and foster an innovation economy that focuses on areas such as health, security and STEM.

The Board of Governors held a meeting on Aug. 28 and 29, where O’Shea presented the progress of the college’s strategic growth.

“At that meeting, we were told that [the SUS] was going to ask for $100 million for Universities of Distinction and to put in proposals,” O’Shea said. “This was the new board chair talking, when they say put in a proposal, it’s kind of an order.”

The FBOG set Sept. 16 as the deadline for proposals. O’Shea returned from the meeting with intentions to immediately inform the faculty about the need to submit a proposal. Because of Hurricane Dorian, O’Shea was not able to start the proposal planning process until a week after the meeting.

“It’s hard to believe” O’Shea said, referencing the short timeline. “It’s a major institutional change but needs to move way faster than normal academic speeds.”

Despite the timeline, O’Shea received a significant amount of feedback from faculty. The deadline was also extended to Sept. 19.

“The faculty came through,” O’Shea said. “About 40 faculty wrote in about substantive things and we had a couple of faculty charrettes, but it was too fast to get students in. It’s hard without consulting students here, I mean, this is a collaborative place. I always feel like I’m violating process but then have no choice.”

Representatives from New College then presented the proposal to the FBOG on Oct. 3 and received feedback.

“I was on a phone call yesterday and they’ve switched their plan a bit,” O’Shea said. “They’ve lowered the amount of funding for preeminent universities and are now asking $65 million for Universities of Distinction. We had put in a proposal of $1.3 million, so now we’re going to cut it to $700,000.”

“New College Tomorrow: Arts and Sciences for Florida’s Future”

Following the Universities of Distinction key goals, the proposal, “New College Tomorrow: Arts and Sciences for Florida’s Future,” outlined three main goals: executing the college’s strategic plan to grow enrollment, inflecting student experience toward the world of work and increasing collaborative agreements with regional institutions. The goals also drew upon recommendations O’Shea received from the Arts and Sciences report.

“One is our strategic plan because they had just given us $10 million to do that,” O’Shea said.

In the proposal, this initiative is described as the “first and central strand.” The college plans to continue its attempt to grow to 1,200 students and 120 faculty, with the additional support staff and programs to achieve a four-year graduation rate of 80 percent.

“We’re also going to orient things so that we’re not just oriented towards graduate school—which we’re doing really well on—but we want students to be able to do better in a job market, which is music to [the SUS’s] ears anyway,” O’Shea said. “It’s also true that most of this generation of students remembers their parents struggling with the recession, so jobs matter for a good number of students.”

The second strand thus proposes that the college will systematically integrate opportunities for professional development and practical applications into every student’s experience by deploying three tactics: integrating hands-on learning, having nearly every student pursue more than one target of study—one that relates to academic interests and one that relates to potential career interests—and integrating post-college planning across every student’s college experience from day one.

“With Dwayne Peterson, that’s really going to turn around,” O’Shea said.

The third strand plans to better take advantage of the opportunities the Sarasota-Manatee area offers and to better contribute to the region. The plan states that the college will “dramatically increase articulation and collaborative agreements with other educational institutions in our region and further afield, and aggressively seek out links with research, health, civic institutes and employers in the region.”

“We’re always going to be a really academically-rigorous liberal arts-based place,” O’Shea said. “But I hope we’re also going to be just much more aware of the world, more oriented to the world of work and more connected to the region.”

Information for this article was gathered from flbog.edu, leg.state.fl.us, flsenate.gov, orlandosentinel.com, palmbeachpost.com and heraldtribune.com